Kinship studies

Historically, kinship studies - also known as family or pedigree studies - were a first step in determining whether a behaviour or psychological disorder "runs in families." When the risk of developing a disorder increases within a family, this indicates a potential genetic root of the behaviour.

Historically, kinship studies - also known as family or pedigree studies - were a first step in determining whether a behaviour or psychological disorder "runs in families." When the risk of developing a disorder increases within a family, this indicates a potential genetic root of the behaviour.

Although kinship studies are not used as frequently today, they have been useful in genetic research. Today, kinship studies are more frequently part of larger linkage or association studies.

Kinship studies have several basic characteristics:

- They measure the frequency of a behaviour across generations.

- They measure the frequency of a behaviour within a generation.

- They are often longitudinal.

- They use case-control studies. Case-control studies are retrospective. They clearly define two groups at the start: one with the behaviour/disorder and one without the behaviour/disorder. They look back to assess whether there is a statistically significant difference in the rates of exposure to a defined risk factor between the groups - in this case, to potential genetic inheritance.

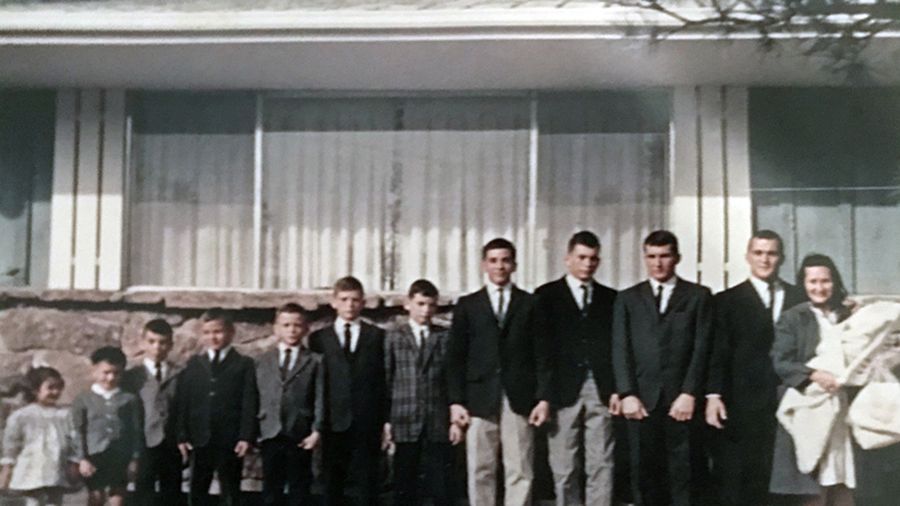

One kinship study took place in the 1960s in Colorado Springs. Don Galvin was a respected member of the Air Force and the father of twelve children - 10 boys and two daughters. Six of his sons would develop schizophrenia.

One kinship study took place in the 1960s in Colorado Springs. Don Galvin was a respected member of the Air Force and the father of twelve children - 10 boys and two daughters. Six of his sons would develop schizophrenia.

The story of the Galvin family is told in Hidden Valley Road by Robert Kolker. Although a tragedy for the family, Lynn DeLisi was able to study the family and eventually was part of a team that used this data to determine a genetic link to schizophrenia.

Siddhartha Mukherjee, author of The Gene: An Intimate History, tells the story of his father's brother Jagu who suffered from schizophrenia and Mukherjee's cousin, Moni, who would also go on to develop the disorder. As Jagu had lived through the partition of India and Pakistan, the family believed that his illness was the result of the tragedy and loss that he had experienced. However, Moni was the next generation and had not experienced this level of trauma. This indicated that there must have been some other reason why these men developed schizophrenia.

The two stories above are a bit different. The case of the Galvin family was studied by DeLisi and her team. They collected empirical data, including blood samples that were eventually used for DNA testing. Mukherjee's story, however, is anecdotal data. Anecdotal data also has value in that it indicates that there is "something here to study." However, it is not as reliable as empirical data.

- Kinship studies limit the overall genetic variability of the sample which increases the statistical power of any ge discovery.

- Kinship studies are more controlled than studies of unrelated people. They have all lived in the same home, shared a common diet, and often have the same level of physical activity.

- It is often difficult to obtain reliable data that goes back more than one generation. Kinship studies are often reliant on anecdotal data with regard to the behaviour of grandparents or great-grandparents. This data may be open to memory distortion. More importantly, it is only recently that a diagnosis of psychological disorders is obtained. In many cases of past generations, there are assumptions made about potential diagnoses - but no clinical data that can be used.

Critically thinking about research

Below you will find three kinship studies of psychological disorders. If you were going to interview these researchers onto your "IB Psychology Podcast," what questions would you ask them about their research?

Below you will find three kinship studies of psychological disorders. If you were going to interview these researchers onto your "IB Psychology Podcast," what questions would you ask them about their research?

Depression: Weissman et al (2005)

Weissman et al (2005) carried out a longitudinal kinship study with a sample of 161 grandchildren and their parents and grandparents to study the potential genetic nature of Major Depressive Disorder. The study took place over a twenty-year period, looking at families at high and low risk for depression. The original sample of depressed patients (now, the grandparents) was selected from an outpatient clinic with a specialization in the treatment of mood disorders. The non-depressed participants were selected from the same local community. The original sample of parents and children were interviewed four times during this period. The children are now adults and have children of their own - allowing for the study of the third generation.

Data was collected from clinicians, blind to past diagnosis of depression or to data collected in previous interviews. Children were evaluated by two experienced clinicians - a child psychiatrist and a psychologist.

The researchers found high rates of psychiatric disorders in the grandchildren with two generations of major depression. By 12 years old, 59.2% of the grandchildren were already showing signs of a psychiatric disorder - most commonly anxiety disorders. Children had an increased risk of any disorder if depression was observed in both the grandparents and the parents, compared to children where parents were not depressed. In addition, the severity of a parent's depression was correlated with an increased rate of mood disorders in the children.

On the other hand, if a parent was depressed but there was no history of depression in the grandparents, there was no significant effect of parental depression on the grandchildren.

OCD: Nestadt et al (2000)

This study had a sample of 80 people living with OCD that were chosen from five different OCD clinics - and 73 control cases chosen by random-digit dialing within the same communities. With their first-degree relatives (parents and siblings), the sample was 343 case and 300 control participants.

First-degree relatives were evaluated by psychiatrists using semi-structured interviews. All interviews were done blindly to control for researcher biases.

The researchers found that the lifetime prevalence of OCD was significantly higher in case compared with control relatives (11.7% vs 2.7%). Case relatives had higher rates of both obsessions and compulsions; however, this finding is more robust for obsessions.

Eating disorders: Lilienfield et al (1998)

Lilienfield et al (1998) carried out a case control study to determine if there is a potential genetic link for eating disorders. The sample was made up of women living with anorexia nervosa (n = 26) or bulimia nervosa (n = 47) and a control group (n = 44). First degree female relatives were also interviewed (n = 460).

All interviews of the AN, BN, and control group were conducted face to face. 85% of the AN group had restored their weight at the time of the interview. Whenever possible, first-degree relatives were interviewed in person; otherwise they were interviewed by telephone. The mean number of relatives per group was 3.4 for AN, 3.5 for BN, and 4.3 for the control group. Information was obtained on unavaialable female relatives through family history interviews with all interviewed family members serving as informants.

Researchers carried out structured interviews. One of the interview schedules was the Eating Disorders Family History Interview to determine eating disorders and disordered eating behaviours. They also used the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria , in order to deterine the lifetime prevalence of depression, OCD, and other mental health concerns.

Relatives of anorexic and bulimic probands had increased risk of disordered eating behaviours, but not a diagnosis of AN or BN. The risk of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder was higher only among relatives of anorexic probands. The prevalence of major depressive disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder was independent of that of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa - that is, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of these disorders between the eating disorder probands and the control group.

There are several potential questions that could be asked about any one of these studies. For example:

- Are you worried that data was only collected at one time? Can you be sure that the data is consistent over time?

- To what extent do you believe that the family members were honest about their own psychological history? Could their answers be influenced by expectancy effect?

- What was the cultural background of your sample? How do you think that a lack of diversity may have affected the results of your study?

- Some of this research here is quite old. Do you think that a change in the DSM may change the outcomes of your research?

- To what extent can you argue that genetics is the reason for the significant findings? Is there potentially a variable within these families that could be argued to be the reason for the disorders?

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team