Kimball (1986)

Social cognitive theory argues that we may be enculturated by observing the behaviour of others. This includes the development of our gender roles and/or gender identity.

Social cognitive theory argues that we may be enculturated by observing the behaviour of others. This includes the development of our gender roles and/or gender identity.

Trying to determine the role of social factors in behaviour is a difficult task as experimental work that is also naturalistic is rarely able to isolate variables. This is why a series of studies done in the 1980s when television was introduced to remote communities in places like McMurdo was important. They allowed for natural experiments that, although they cannot establish actual causality, help us to see the potential role of media on one's gender role development.

The sociocultural approach argues that media - whether it be digital or paper - can have a significant effect on our behaviour. The social cognitive theory argues that the modeling of behaviours by characters that children identify with, or want to identify with, will affect their own behaviour. One behaviour that has been explored with regard to the role of modeling in the media is the development of gender roles and gender stereotyping.

Social cognitive theory is based on two basic mechanisms of learning. The first is modeling. The theory argues that children learn gendered behavior by watching others, including parents, peers, teachers, and the media. Children learn best from same-gender models. In addition, children learn to imitate behavior if the model is rewarded for his/her behavior. Finally, attractive role models are particularly influential.

The second mechanism of social cognitive theory is direct tuition, in which children are encouraged and rewarded for engaging in behaviors considered appropriate for their sex, and are discouraged from gender-inappropriate activities. Parents play an important role in this way of learning as they are the ones that provide toys for their children and choose what to read them before going to bed at night. However, once a child enters preschool, peers also engage in direct tuition by reinforcing gender-typed toy selection and gendered behaviour.

The following classic study looked at the role of television on the development of gender stereotypes in elementary school children.

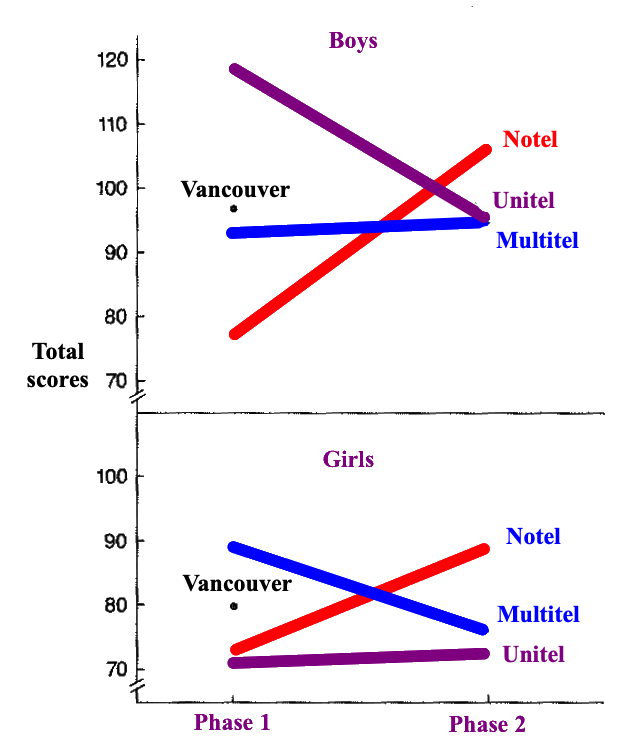

Kimball (1986) carried out a natural experiment, taking advantage of the introduction of television in a remote area of McMurdo. She wanted to see if exposure to "normal television viewing" would lead to a change in the level of gender stereotyping in a Northern Canadian community.

The participants were 536 children in four different communities. The sample consisted of 130 children from Notel (that is, No Television), 135 from Unitel (one station), 166 from Multitel (more than one station), and 105 from Vancouver. Both Unitel and Multitel were from the same geographic region. Vancouver was used as a control.

The children's level of gender stereotyping was measured using the Sex role Differentiation (SRD) scale. The SRD asks children to rate how appropriate or frequent certain behaviours are for boys and girls their own age, as well as how often their mothers or fathers perform certain tasks.

The SRD was administered to all students in grades 6 and 9 in each of the three towns both before and 2 years after television was introduced to Notel. The control group's data was obtained from a previous study that was carried out 8 months before this study began.

The children filled in the questionnaire during normal class time. Since information about the children's parents was requested, the responses were anonymous.

The children filled in the questionnaire during normal class time. Since information about the children's parents was requested, the responses were anonymous.

Before their town had television, Notel children held more egalitarian gender attitudes than children who viewed television regularly. Girls had lower levels of gender stereotyping than boys at the beginning of the study.

Two years after Notel obtained television, gender stereotyping had significantly increased in both the NOTEL boys and girls. In Phase 2, there was no significant difference between the gender stereotyping scores among the boys in the three towns. When looking more carefully at the subscales on the SRD, the Notel boys' stereotypes with regard to gender and jobs had increased significantly.

The study supports that the introduction of television increased levels of gender stereotyping.

* If you would like to read a graphic "novel" about this study, please see Stuart McMillan's fantastic site.

The study is a natural experiment, so ecological validity is high. However, since the researcher did not manipulate the independent variable, participants were not randomly allocated to conditions, and there was no ability to control for extraneous variables, the study has low internal validity and causality cannot be determined.

The study is quite dated, so it is difficult to determine the study's temporal validity - that is, whether the findings can be generalized to modern society. However, there is modern research that shows similar findings (see the box below).

Since the data were anonymous, this means that the researchers did not compare data from phase 1 and phase 2 for specific children. Instead, the study is cross-sectional. The researchers could not see changes in the gender stereotypes of individual children over time.

Coyne et al (2016) examined children's level of engagement with Disney Princess media and gender-stereotypical behavior.

Participants consisted of 198 children (mean age of 4.8 years old). The children were tested twice, approximately one year apart. Longitudinal findings showed that Disney Princess engagement was associated with more female gender-stereotypical behavior 1 year later.

The researchers argue that being "feminine" is not a problem. However, stereotypical female behavior may potentially be problematic if girls believe that their opportunities in life are limited because of preconceived notions regarding gender or if they avoid the types of exploration and activities that are important to children learning about the world in order to conform to stereotypical notions about femininity (Coyne, p 1921).

Dinella (2013) found that grown women who self-identified as “princesses” gave up more easily on a challenging task, were less likely to want to work, and were more focused on superficial qualities.

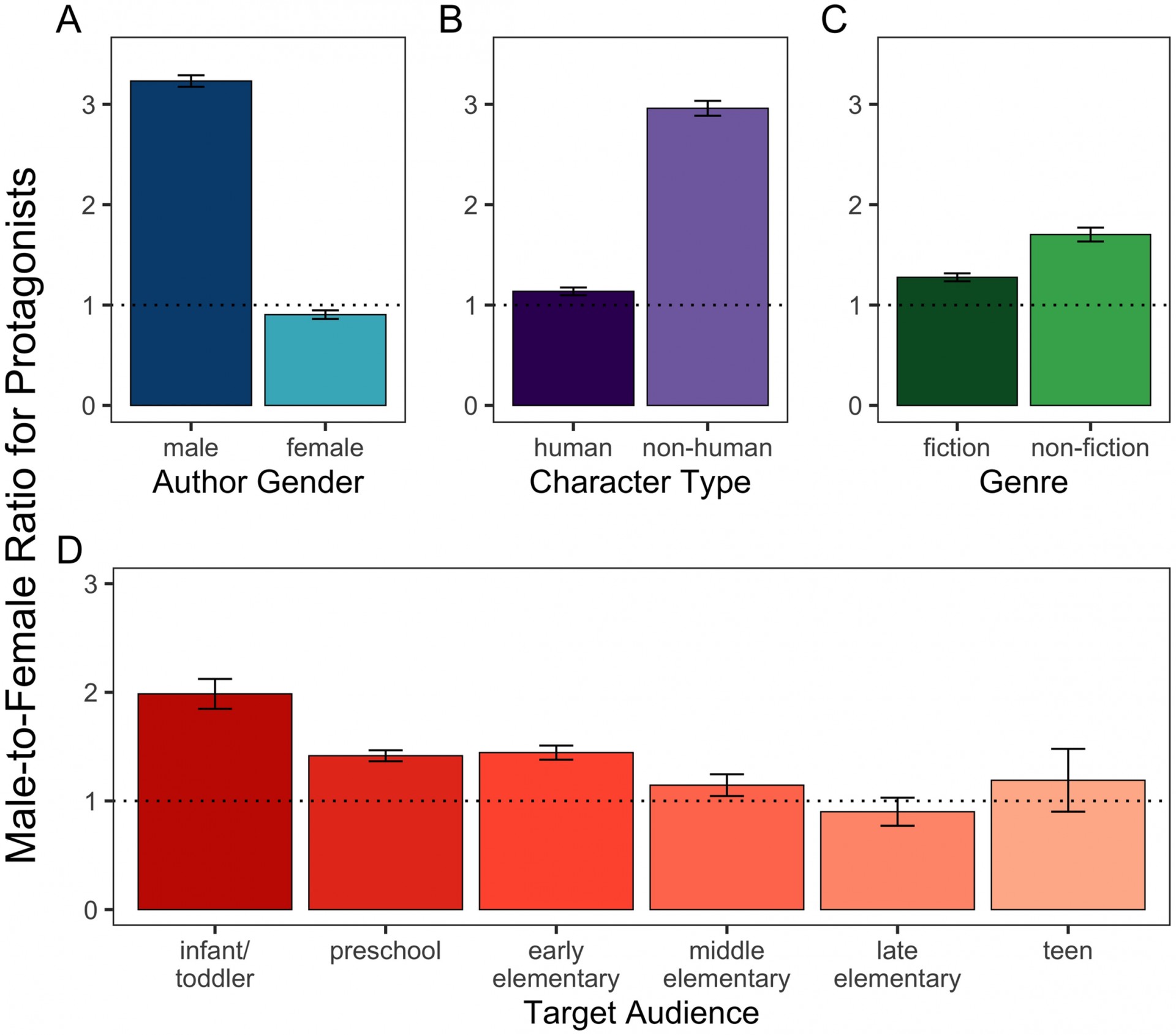

Casey, Novick, and Lourenco (2021) recently published a study to investigate how gender-stereotyped roles in children's books have changed since 1960. They analyzed 3280 children's books published between 1960 and 2020 to determine the proportion of male and female protagonists. The following graph shows their findings.

The researchers found that although the proportion of female protagonists has increased over this 60-year period, male protagonists remain overrepresented even in recent years.

The researchers found that although the proportion of female protagonists has increased over this 60-year period, male protagonists remain overrepresented even in recent years.

Other findings include:

* Non-human characters are overrepresented as male, but only in fiction books.

* Human characters are also overrepresented as male in non-fiction books.

* Male authors showed improvement in the male-to-female ratio of central characters across the 60-year period, but this was limited to books targeted to younger children.

* Female authors continue to overrepresent males in books with non-human characters

The researchers noted that their study shares a common limitation of such research - their analyses do not reflect actual reading rates. In other words, they analyzed children’s books to estimate general trends in gender roles, but they did not measure the popularity of the books and the frequency that they are read by various age groups.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team