Cognitive explanations of obesity

.jpg) Cognitive theory can be used to explain why people choose to eat the foods that they do. Making decisions about healthy eating can be difficult - and you know that we prefer System 1 thinking. As cognitive misers, we often don't take the time to do the research. In addition, the stressors of daily life fill up cognitive load, making it difficult to concentrate on making healthy food options. Cognitive psychologists argue that if we want to fight the obesity epidemic, we have to change the way we think about food.

Cognitive theory can be used to explain why people choose to eat the foods that they do. Making decisions about healthy eating can be difficult - and you know that we prefer System 1 thinking. As cognitive misers, we often don't take the time to do the research. In addition, the stressors of daily life fill up cognitive load, making it difficult to concentrate on making healthy food options. Cognitive psychologists argue that if we want to fight the obesity epidemic, we have to change the way we think about food.This scene from Supersize me looks at how television plays a role in a child's attitude toward food.

Human beings are cognitive misers. Baumeister et al (1998) argued that making decisions actually uses energy which we would rather not use. As human beings, we tend to apply the following mantra to decision making: I don't know, I don't care and I don't have time.

In order to eat healthy food and thereby maintain a healthy weight, I would have to know what to look for when reading the labels on food products. In addition, you have to care about healthy eating. Finally, many of us feel that we don't have time to read all the labels in the grocery store or to educate ourselves on healthy eating. That is why we use heuristics - that is, short-cuts to decision making which are often irrational in nature. Heuristics are simple procedures that help individuals find adequate, though often imperfect, answers to difficult questions.

One heuristic that seems to affect eating behaviour is the representativeness heuristic. When the children above see Ronald McDonald, they associate him with positive images. Therefore, he represents a positive lifestyle - and thus good eating. When people make rapid decisions they rely on heuristic cues, such as the appearance of objects, familiar pictures, shapes, sizes, logos, brands, and prices. This automatic decision-making mechanism allows people to function efficiently and frees up limited attention and cognitive capacity to address other demands.

One heuristic that seems to affect eating behaviour is the representativeness heuristic. When the children above see Ronald McDonald, they associate him with positive images. Therefore, he represents a positive lifestyle - and thus good eating. When people make rapid decisions they rely on heuristic cues, such as the appearance of objects, familiar pictures, shapes, sizes, logos, brands, and prices. This automatic decision-making mechanism allows people to function efficiently and frees up limited attention and cognitive capacity to address other demands.

Many food products use signs and symbols in their packaging that suggest a product is healthier than it really is in order to promote sales. Tversky & Kahneman have shown that the representativeness heuristic is often used to make decisions - that is, if there are cues that make it look healthy, then it must be healthy.

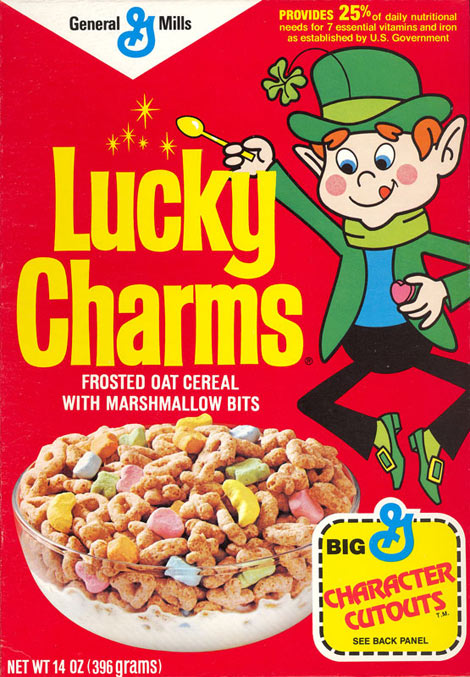

In his book, The Social Animal (pp 156 - 157) Elliot Aronson writes about a consumer study done on the role of heuristics in food choice. Parents were asked whether they would buy Lucky Charms (an American breakfast cereal) or Quaker's 100% Natural for their children. Parents easily chose the Quaker's 100% Natural. Both the name and the picture of fields of the wheat on the box told them that it was healthier. They had used the representativeness heuristic to make the decision, rather than doing a bit of research.

In 1981 the magazine Consumer Reports conducted a test of breakfast cereals. Their researchers fed young rats, which have nutritional requirements very similar to humans, an exclusive diet of water and one of thirty-two brands of breakfast cereal for a period of eighteen weeks. They found that the rats grew and remained healthy on a diet of Lucky Charms. This was not the case with a diet of Quaker's 100% natural. A careful look at the ingredients shows that Lucky Charms is lower in calories and in saturated fats than 100% Natural. While it is also slightly higher in sugar, this difference is of no dietary significance. In this case, judging the cereal by its box led to a false assumption about the healthy nature of the cereal.

Visual cues can also lead to an illusory correlation, as seen in the study by Song and Schwarz (2008). In their study, they asked 20 participants (12 female, 8 male) to read instructions for a new exercise plan. The instructions were either written in an easy-to-read or a difficult-to-read font. The participants who read the directions in the easy-to-read font estimated that the plan would be easier and more enjoyable - and that they would be more willing to try the plan, than those that read the difficult-to-read font. It seems that the participants made an illusory correlation - that is, if the text is difficult to read, then the exercise must also be difficult to do.

The role of perception

In the following video, Emily Balcetis discusses the role of perception in one's motivation to exercise. Maybe some people perceive the finish line as further away than others. What would this mean for their motivation and goal setting? Watch the video and think about how her research supports or challenges some of the research in this chapter.

Another argument is that high cognitive load may impair our ability to make good decisions. Pascoe and Richman (2010) found that women who were able to recall more examples of personal discrimination - or who were given unjustified negative feedback on a task - were more likely to choose a chocolate bar over a granola bar than women who recalled fewer examples of discrimination or received fair feedback. Of course, this is done under controlled conditions and is not a longitudinal study - so, although it may give us some insight into how people make food choices, it may not necessarily explain obesity.

One of the great areas of cognitive psychology is the theory that our beliefs can affect our behaviour - and in some cases, even our physiology. The following study by Aila Crum is an intriguing example of how our beliefs may affect the way our body processes food.

Research in psychology: Crum (2011)

Crum et al (2011) carried out a study to see if one's perception of the number of calories in a milkshake would affect their body's response and their subjective feeling of satiety (fullness).

Crum et al (2011) carried out a study to see if one's perception of the number of calories in a milkshake would affect their body's response and their subjective feeling of satiety (fullness).

The sample was made up of 46 participants who were recruited by posting fliers in the local community. The participants were asked to take part in a "shake tasting study." The participants were between 18 and 35-years-old and were all within a normal range of body mass – that is, there were no obese participants. 78% of the sample was made up of university students.

The participants were asked to attend two tasting sessions that were one week apart. In this repeated measures design, in one visit they drank the "indulgent shake" - which they were told had 620 calories; in the second session, they were given the "sensible shake" with only 140 calories.

However, they were actually the same shake, with 380 calories. The only difference was how many calories the participants believed were in the shake. Prior to the experiment, they were asked to not eat any breakfast before showing up for their 8 am meeting with the researchers.

The study was counterbalanced so that some drank the indulgent shake the first week and some drank the sensible shake the first week. The participants also had three tests to measure their ghrelin levels - one at the beginning to measure the baseline level of ghrelin, one just before consuming the shake (the anticipation condition) and one after consuming the shake. They were also asked how they liked the shake, how attractive it looked, how enjoyable it was and whether they thought it was a healthy choice. This was done to make sure that they had the appropriate mindset. Finally, they were asked whether they felt "full" after drinking it.

The researchers found that when the participants thought that they were drinking the indulgent shake, they had a steep decline in ghrelin after consumption, whereas when they drank the "sensible shake," ghrelin levels remained relatively flat. The participants' reporting on satiety was consistent with what they believed they were consuming, rather than the nutritional value of what they consumed.

Another study of how beliefs can affect eating behaviour was carried out by Wansink, Just, & Payne (2009). In their study, 62 MBA students sat through a lecture explaining that if presented with a one-gallon bowl of Chex Mix, they would eat more than if presented with two half-gallon bowls. The rationale is that they will base their serving sizes on the size of the bowl that is offered. Taking from a larger bowl means that they will consume more than when taking from a smaller bowl. Despite this lesson, the students who served themselves from the one-gallon bowl ate 59% more than the participants who chose from one of two half-gallon bowls. The participants did not believe the size of the serving bowls influenced their behaviour. Wansink argues that this is evidence that sample size matters. But does it?

Linking to TOK

Wansink served as the director of Cornell University's Food and Brand lab for over a decade. He also played a role at the national level in trying to improve healthy eating and reduce obesity. However, in 2018 several of his studies were retracted. These studies were retracted due to errors in reporting the sample, details of the procedure or the statistical significance of the findings. One particular charge is that he engaged in p-hacking - that is, manipulating your data until the results are significant. This may be done by eliminating some data, changing the degrees of freedom, or by rewriting the original hypothesis.

In an interview that appeared in Atlantic magazine, Wansick argues that although he made mistakes, the research has been used in a way that has benefitted Americans and has changed the way we eat.

What do you think of Wansick's argument? Which is more important? Statistical significance or the application of the research, regardless of its flaws?

As part of the discussion of Wansick's work, you may want to show students this video on the problems of replicability.

The discussion of whether the p-values matter in Wansick's case can be an interesting discussion. The fact that he changed people's eating habits for the better is a positive outcome from poorly done research. So, arguing that portion size matters or that we should eat more slowly is not in and of itself problematic. However, the problem is that allowing such research to remain "published" undermines people's trust in science. It is important that scientific journals respond quickly when fraudulent data is discovered. To not do so makes it possible for people to question the validity of any scientific research - and that could undermine people's trust in public health.

- Theories can be tested under controlled conditions, potentially indicating a cause-and-effect relationship.

- Using highly standardized procedures, the research can be replicated, testing for the reliability of the findings.

- The theories have been applied successfully in weight-loss programs.

- Although there is some evidence that the way that we think may influence our choices of when, what and how much to eat, many of the studies are done under artificial conditions.

- It is not possible to actually know the thinking processes that people engage in during the time of overeating.

- Many of the studies look at food-choice, making the assumption that this may play a role in obesity.

- As research is often done under lab conditions, sample sizes tend to be small.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team