Neisser & Harsch (1992)

Neisser & Harsch carried out a classic study of flashbulb memory. You can use this study for the following content:

Neisser & Harsch carried out a classic study of flashbulb memory. You can use this study for the following content:

Research methods used in the cognitive approach.

To what extent is one cognitive process reliable?

The abstract of the original study is available here.

If you ask anyone where they were on September 11th, the day that two airplanes were used to attack the World Trade Center in an act of terrorism, they will give emotional detail about what they were doing at the time. These vivid memories that are connected to such emotional moments in our lives are often referred to as “Flashbulb memories.” Flashbulb memories are highly detailed, exceptionally vivid 'snapshots' of the moment and circumstances in which surprising and personally relevant news was heard.

Because of the emotional and highly personal nature of flashbulb memories, it is believed that they are highly resistant to forgetting. Flashbulb memories are one type of autobiographical memory. The accuracy of these memories, however, is debatable. A number of studies suggest that flashbulb memories are not especially accurate, but that they are experienced with great vividness and confidence.

Much recent research has focused on the events of September 11th. Talarico & Rubin (2003) recorded 54 Duke University students’ memory of first hearing about the terrorist attacks of September 11 and a recent everyday event. They tested again either one, six, or thirty-two weeks later. Both the flashbulb and everyday memories declined over time. However, ratings of vividness and belief in accuracy declined only for the everyday memories. The power of the emotion related to the event correlated with belief in accuracy, but not actual accuracy of the memory. This led the researchers to conclude that flashbulb memories are not special in their accuracy, but only in their perceived accuracy.

In 1992 Neisser & Harsch challenged the prevailing belief in flashbulb memory and argued that these memories are also prone to significant distortion. In order to do this, they had students recall their reactions to the Challenger disaster – an accident on January 28, 1986, in which a space shuttle exploded in space, live on television. The event was being watched around the world. One of the most celebrated members of the crew was a school-teacher named Christa McAuliffe.

The aim of the study was to determine whether flashbulb memories are susceptible to distortion.

On the morning after the Challenger disaster – less than 24 hours after the event - 106 Emory University students in an introductory psychology course were given a questionnaire at the end of the class. They were asked to write a description of how they heard the news. On the back of the questionnaire was a set of questions:

- What time was it?

- How did you hear about it?

- Where were you?

- What were you doing?

- Who told you?

- Who else was there?

- How did you feel about it?*

- How did the person who told you seem to feel about it?*

- What did you do afterwards?

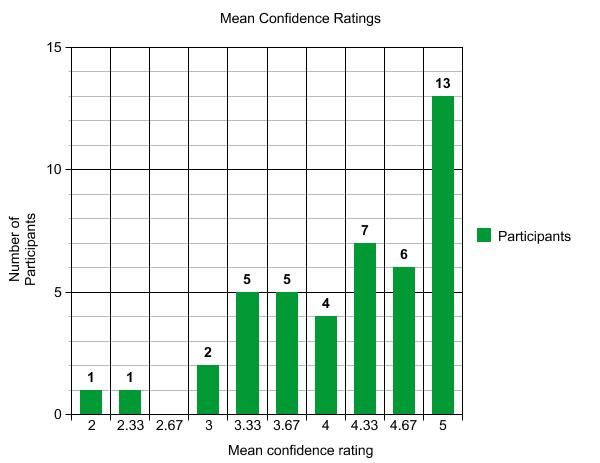

2 ½ years later they were given the questionnaire again. 44 of the original students - 30 women and 14 men - were now seniors at the university. They were not told the purpose of the study until they arrived. They were given the original questionnaire to fill in again. This time they were also asked for each response to rate how confident they were of the accuracy of their memory on a scale from 1 (just guessing) to 5 (absolutely certain).

They were also asked if they had filled out a questionnaire on this subject before. Incredibly, only 11 participants or 25% said yes!

Seeing that there were discrepancies, semi-structured interviews were carried out a few months later in order to determine if the participants would repeat what they had written a few months earlier or revert to the original memory. The interviews were taped and transcribed. The interviewer presented a prepared retrieval cue with the hope of prompting the original memories. Participants whose 1988 recall had been far off the mark were given a cue based on their original records; for example, the interviewer might ask “Is it possible that you already knew about the explosion before seeing it on television?”

At the end of the interview, the participants were shown their original 1986 reports in their own handwriting.

The researchers were surprised to see the extent of the discrepancies between the original questionnaire and the follow-up 2 ½ years later. Here is a typical example:

24 hours after the accident: I was in my religion class and some people walked in and started talking about it. I didn’t know any details except that it had exploded and the schoolteacher’s students had all been watching which I thought was so sad. Then after class, I went to my room and watched the TV program talking about it and I got all the details from that.

2.5 years later: When I first heard about the explosion I was sitting I my freshman dorm room with my roommate and we were watching TV. It came on a news flash and we were both totally shocked. I was really upset and I went upstairs to talk to a friend of mine and then I called my parents.

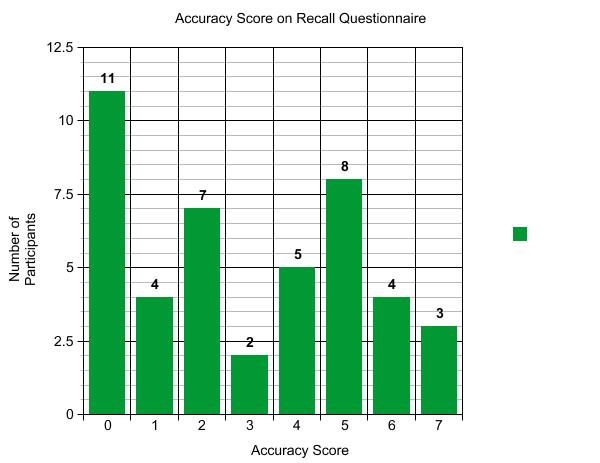

In order to come up with a “score,” the researchers looked at the seven “content” questions – that is, not the two that are about emotion (see asterisks above) – and gave a point if they matched the original response. The maximum total response was then seven.

The mean score was 2.95/7.0. Eleven participants scored 0. Twenty-two of them scored 2 or less. Only three participants scored the maximum score of 7. What is interesting is that in spite of the lack of accuracy, the participants demonstrated a high level of confidence. The average level of confidence for the questions was 4.17.

For the most part, participants told the same story in the spring as in the fall, when they were interviewed. Additional cues had little effect on accuracy. When presented with the original questionnaire, participants were surprised and could not account for the discrepancies.

The study was a case study. The strength of this method is that it was both longitudinal and prospective. There was also method triangulation - both questionnaires and interviews were used. The limitation is that it cannot be replicated. In addition, there was participant attrition - that is, participants who dropped out of the study over time.

The study has high ecological validity. The researcher did not manipulate any variables and the study was not done under highly controlled conditions.

The study was naturalistic. Although this is good for ecological validity, it is difficult to eliminate the role of confounding variables. There was no control over the participants' behaviour between the first questionnaire and the second. We have no idea how often this memory was discussed or how often the participants were exposed to media about the event.

It is possible that the confidence levels were higher than they should have been as a result of demand characteristics - that is, since the participants were asked to verify their level of confidence, they could have increased their ratings to please the researcher or avoid social disapproval for claiming not remember an important day in their country's history.

As mentioned in the background section above, there are several studies of different events - like September 11th - which seem to have the same results. This demonstrates the transferability of the findings of this study to other situations.

Neisser, U. & Harsch, N. (1992). Phantom flashbulbs: False recollections of hearing the news about Challenger. In E. Winograd & U. Neisser (Eds.), Affect and accuracy in recall: Studies of "flashbulb memories", pp. 9-31. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pezdek, K. (2003). Event memory and autobiographical memory for the events of September 11, 2001. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 17, 1033–1045.

Talarico, J. M. & Rubin, D. C. (2003). "Confidence, not consistency, characterizes flashbulb memories", Psychological Science, 14(5), 455-461.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team