Sparrow (2011)

Sparrow et al, 2011 wondered if the Internet has become an enormous transactive memory store. If this is true, then individuals no longer feel the need to remember information but simply need to remember how to search for it effectively using a search engine such as Google.

Sparrow et al, 2011 wondered if the Internet has become an enormous transactive memory store. If this is true, then individuals no longer feel the need to remember information but simply need to remember how to search for it effectively using a search engine such as Google.

Below you will find the two-part study which led to the famous "Google Effect." You do not need to know both parts of the study, but the two experiments do complement each other. Both studies are appropriate for a discussion of the HL extension - effects of technology on cognition.

The Google effect, also called digital amnesia, is the tendency to forget information that can be found readily online by using Internet search engines. The flip side is that information that is not easily retrievable online will be more easily remembered.

It is difficult to determine whether this is a positive or negative effect of technology. Remember, this effect only works for declarative memory, but not other types of memory. Here is a good quick overview of digital amnesia.

Sixty undergraduate students (37 f, 23 m) at Harvard University were asked to type 40 trivia facts into the computer. Some of the facts were expected to represent new knowledge (An ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain) whilst other facts were more likely to be already known to the participants (The space shuttle Columbia disintegrated during re-entry over Texas in Feb. 2003).

The experiment used a 2 x 2 independent samples design – meaning that two independent variables were manipulated at two different levels.

Participants were presented with trivia statements one by one on a computer screen. They were asked to read the statements, and then type what they read into a dialog box which appeared below the statement. Half of the participants were told to press the spacebar to save what they typed to the computer, and that they would have access to what they typed at the end of the task. The other half were told to press the spacebar in order to erase what they just typed so that they could type the next statement. In addition, half were told to try to remember the statements, and half were told nothing.

This means that four conditions were present in the study:

Save Remember | Save not asked to remember |

Erase Remember | Erase not asked to remember |

They were then given a blank piece of paper and asked to recall as many of the facts as they could in ten minutes. Then they were given a recognition task where they were given forty statements and asked to identify (yes or no) whether they were exactly the same as what they saw on the computer screen.

Percentage of trivia facts recalled

Asked to remember | Not asked to remember | |

Computer will save info | 19 | 22 |

Computer will erase info | 29 | 31 |

The results showed that being asked to remember the information made no significant difference to the participants’ ability to recall the trivia facts, but there was a significant difference if the participant believed that the information would be stored in the computer. Participants who believed they would be able to retrieve the information from the computer appear to have made far less effort to remember the information than those who knew they would not be able to do this.

In a follow-up study, Sparrow et al tried to measure how well people recall where information can be found compared to recall of the information itself. In this experiment, 34 undergraduate participants (16 f; 18 m) from Columbia University were asked to read and type a series of 30 trivia facts. After typing each fact, the computer would give them feedback such as "Your entry has been saved into the folder INFO." There were six folders in total; participants were not told the list of folders.

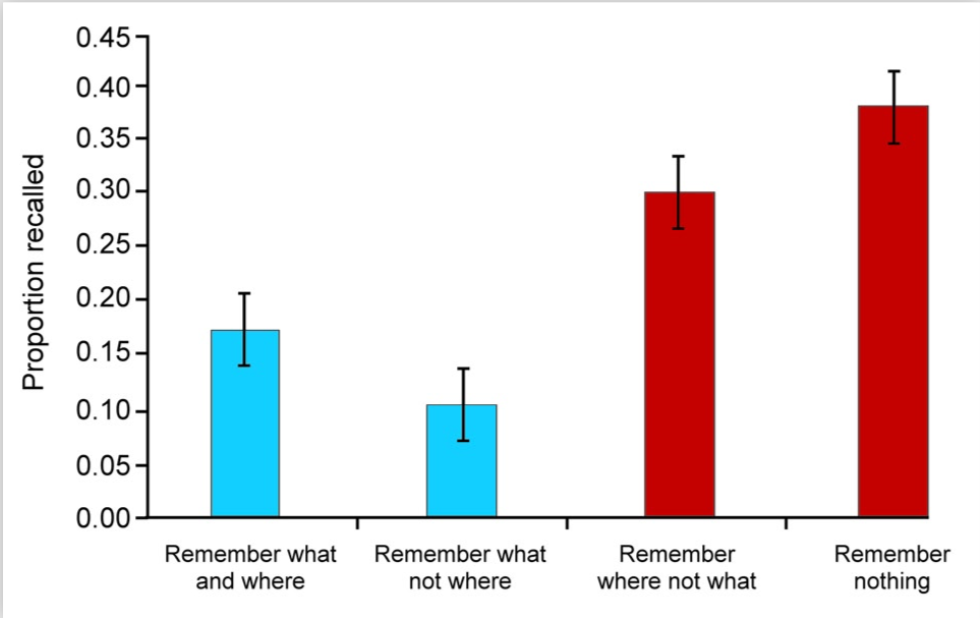

Participants were then given ten minutes to write down as many of the statements as they could remember. They were then given a part of a statement and asked which folder it was saved in. For example, “What folder was the statement about the ostrich saved in?”

Percentage of recall

Mean | Standard deviation | |

Recall both statement and folder | 17 | 16 |

Recall statement, but not the folder | 11 | 08 |

Recall folder, but not the statement | 30 | 16 |

Recalled neither statement nor folder | 38 | 24 |

Participants were much more likely to remember the name of the folder (i.e. where the information could be found) than the information itself. The highest rate of recall was for the name of the folder when the information itself was forgotten, suggesting that participants were prioritizing their memory of where information could be found, exactly as expected if we are using the Internet as an external store in a transactive memory system. It appears that our confidence in this external store appears to discourage us from investing effort in encoding and/or retrieval of potentially important information in our individual long-term memory stores.

- The study was rather groundbreaking and introduced the concept of digital amnesia. Surveys done by the Kaspersky Lab have found that people cannot remember basic information (addresses, telephone numbers) that used to be common knowledge.

- Attempts to replicate Sparrow's findings have not been successful. The failure of replications studies challenges the reliability of these findings.

- The tasks had low ecological validity. In addition to knowing that they were part of an experiment, the information that they were being exposed to was of limited value or interest to the students. Research shows that we tend to remember information that we process deeply and that is of personal relevance. Neither of these two variables was measured in these studies.

- It is highly possible that there were demand characteristics and that the aim of the research was figured out by participants.

- The sample was made up of university students who are used to memorizing and using a computer. This may not reflect the more general population.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team