Gender identity

When a woman announces that she is pregnant, people often ask "Do you know if it's a boy or a girl?" The biological sex of a child plays an important role in the identity of the children from the day of its birth. Within a couple of years, the children themselves declare that they are a boy or a girl, and behave accordingly. Are there innate psychological differences between men and women, or are the differences due to socialization? Nearly all societies expect males and females to behave differently and to assume different social roles - or gender roles. In order to live up to such expectations, the child must learn what it means to be a boy or a girl in the culture in which he or she is raised. Researchers agree that gender role socialization begins as soon as the newborn child has been identified as a boy or a girl. How the children identify with their gender - and the way that society treats them as a result - plays a key role in their identity development and sense of self.

When a woman announces that she is pregnant, people often ask "Do you know if it's a boy or a girl?" The biological sex of a child plays an important role in the identity of the children from the day of its birth. Within a couple of years, the children themselves declare that they are a boy or a girl, and behave accordingly. Are there innate psychological differences between men and women, or are the differences due to socialization? Nearly all societies expect males and females to behave differently and to assume different social roles - or gender roles. In order to live up to such expectations, the child must learn what it means to be a boy or a girl in the culture in which he or she is raised. Researchers agree that gender role socialization begins as soon as the newborn child has been identified as a boy or a girl. How the children identify with their gender - and the way that society treats them as a result - plays a key role in their identity development and sense of self.

When children are around two years old, they can correctly label their own or another person’s sex or gender. This is called gender identity. Kohlberg (1966) carried out interviews with young children between the ages of 2 and 3 and found that children often believed that they could grow up and become a different gender - for example, little boys wanted to grow up to be a mother.

Development of gender identity is a step towards assuming a gender role, but it is only around the age of seven that children develop gender constancy - the realization that no matter what clothes you wear or what you do, you still remain a male or a female. Kohlberg found that children often attributed gender to physical characteristics - so, for example, a boy could become a girl by letting his hair grow long.

Men and women tend to occupy different social roles, and in most cultures there are norms for "appropriate" or gender congruent behaviour, according to biological sex. Children are socialized to assume appropriate gender roles through child-rearing practices. Whiting and Edwards (1973) studied children aged 3 - 11 in Kenya, Japan, India, the Philippines, Mexico, and the USA. In the majority of these societies, girls were more nurturing. Boys were more aggressive, dominant, and engaged in more rough-and-tumble play. The researchers interpreted the gender differences in the six cultures as differences in socialization pressures - that is, the tasks that the children are assigned by their parents and the frequency of interaction with different categories of individuals - infants, grandparents, peers - i.e., infants, adults, and peers. For example, in many societies older girls were required to perform “nurturing tasks”, such as looking after younger siblings.

There has long been controversy about the relative importance of either nature or nurture in the development of gender roles. The nature view argues that basic biological and hormonal factors are important in the development of gender identity. The nurture view claims that the way a child is treated is the most important factor in the development of gender identity. Modern psychology does not argue that it is either-or, but rather the interaction of both biological and environmental factors that shapes our gender identity and the gender roles that we adopt.

Psychological vocabulary

- Sex: biological sex - that is, whether one has the genitalia of a male or female

- Gender: the social expectations and practices associated with being a man or a woman

- Gender identity: the psychological sense of oneself as a man or a woman

- Gender-role: a set of prescriptive culture-specific expectations about what is appropriate for men and women

Biological explanations

Biological theorists argue that the development of gender is dictated by physiological processes within the individual and develops as a part of physical maturation. From a biological perspective, one's sex is determined by a pair of sex chromosomes. Girls have two X chromosomes, whereas boys have an X and a Y chromosome. During prenatal development, sex hormones are released, causing the external genitals and internal reproductive organs of the fetus to become male or female. It is the presence or absence of male hormones (androgens) that makes the gender difference.

Biological theorists argue that the development of gender is dictated by physiological processes within the individual and develops as a part of physical maturation. From a biological perspective, one's sex is determined by a pair of sex chromosomes. Girls have two X chromosomes, whereas boys have an X and a Y chromosome. During prenatal development, sex hormones are released, causing the external genitals and internal reproductive organs of the fetus to become male or female. It is the presence or absence of male hormones (androgens) that makes the gender difference.

Some researchers argue that testosterone has a masculinization effect on the brain of the developing child, which explains behavioural differences and gender identity in children. This is the theory of psychosexual differentiation. The theory argues that the hormone testosterone is the key to developing the body as well as the mind. Prenatal exposure to testosterone establishes a male brain circuitry and inhibits the development of female brain circuits. According to this theory, prenatal exposure to hormones is the most important factor in the development of gender identity, and socialization plays a secondary role.

Imperato-McGinely et al (1974) carried out a case study of the Batista family in the Dominican Republic. Due to genetic mutation, some children were born with what appeared to be the genitalia of girls, but physically developed into men at puberty. Research showed that the genetic variation led to a lack of production of testosterone which, although they had the "XY" chromosome, did not allow for the production of a penis. At puberty, like other boys, they got a second surge of testosterone. This time the body did respond and they sprouted muscles, testes and a penis.

Throughout their childhood, they were raised as girls. However, as adults, they demonstrated clearly masculine gender roles and heterosexual behaviour. Interviews with children who had changed from female to male recalled never being happy doing "girl things."

This seems to indicate a strong biological origin of our gender identity. A classic study in psychology attempted to disprove this and argue that, instead, we are born gender-neutral and are socialized into our gender identity.

Research in psychology: Money and Erhard (1972)

The view that socialization is the most important factor in gender identity was addressed in the theory of “gender neutrality”, or the biosocial theory of gender development, suggested by Money and Ehrhardt (1972). The theory argued that the interaction between biological and social factors is important, rather than simply the direct influence of biology. Money and Ehrhardt claimed that biological factors such as hormones, in combination with how the child is labeled sexually, determine the child's gender identity.

The view that socialization is the most important factor in gender identity was addressed in the theory of “gender neutrality”, or the biosocial theory of gender development, suggested by Money and Ehrhardt (1972). The theory argued that the interaction between biological and social factors is important, rather than simply the direct influence of biology. Money and Ehrhardt claimed that biological factors such as hormones, in combination with how the child is labeled sexually, determine the child's gender identity.

Money based his theory on case studies of individuals born with ambiguous genitals - or intersex. This could be a baby girl born with masculinized genitals because she was exposed to high levels of testosterone while in the womb. Money found that children who had been born as genetically female but were raised as boys, thought of themselves as boys. Money then theorized that humans are not born with a gender identity and that it is, therefore, possible to reassign sex within the first two years of life. Psychologically, the child would adopt the assigned gender identity and grow up to be perfectly happy.

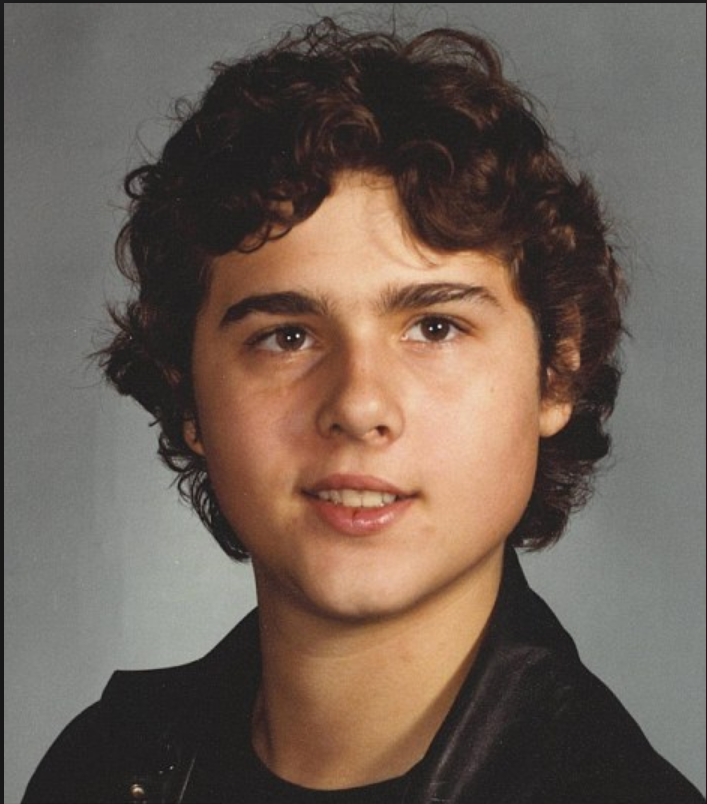

One of the most famous case studies in psychology indicates that this theory may be problematic. The researchers carried out a case study on a boy named David Reimer (see photo). David was raised as a girl (Brenda) after losing his genitalia due to an accident during circumcision. In spite of being raised a girl, he always felt that he was a boy and eventually had sexual recorrection surgery.

Money published scientific articles regarding the case that appeared to confirm his theory, but later interviews with David contradicted Money's findings. The case study seems to indicate that Money was not correct about gender neutrality; the study actually seems to support the theory of psychosexual differentiation.

Evaluation of biological arguments

It is difficult to isolate biological factors in studying development. There is no real way to test if our gender identity is based solely on biological factors. In addition, this would be a rather reductionist approach to understanding gender.

Research with rats has shown that injecting female rats with testosterone while still in the womb has an effect on their gender behaviours, but it is difficult to generalize this to human behaviour. Similarly, many of the studies that are done are case studies of "extreme cases" and may not explain gender development in the general population.

ATL: Reflection

Before watching the video below, reflect on how important your gender is to you. To what extent is it an essential part of your identity?

After watching this video, can you explain what Alice Dreger means when she says, "Nature doesn't draw the line for us between male and female; we actually draw that line on nature"?

The statement itself is rather controversial, so students may choose to disagree with the statement, but they should defend their position. Dreger is arguing that although your biological sex is determined by nature, the behaviours associated with your gender are culturally determined.

Gender schema theory

The cognitive approach examines the role of schema in gender development. Gender Schema Theory argues that once children can categorize boys and girls and recognize which group they belong to, they will actively seek out information to build up their schema.

Children’s tendency to categorize on the basis of gender leads them to perceive boys and girls as different. Once they have identified themselves as male or female, they are motivated to be like others in their group, and this leads them to observe same-sex role models more carefully. According to Martin and Halvorson, children have mental representations of what is suitable for boys and for girls. They have a gender schema for their own sex (the in-group) and for the opposite sex (the out-group). These schemas include information about attributes, activities, and objects that are gender consistent. Gender schemas determine what children pay attention to, what they interact with, and what they remember. A boy is generally more interested in toys or activities that conform to his gender schema, and he will be more likely to imitate same-sex models. Cultural beliefs about females and males are incorporated in the gender schema, and this influences the way children think about themselves and their possibilities.

Martin & Halverson (1983) carried out an experiment to see if children of both genders between the age of five and six would experience memory distortion as a result of gender schema. The researchers showed the children pictures of males and females in activities that were either in line with gender role schemas - for example, a girl playing with a doll - or inconsistent with gender role schemas - for example, a girl playing with a toy gun. A week later, the children were asked to remember what they had seen in the pictures. The children had distorted memories of pictures that were not consistent with gender role schemas - they remembered the picture of a girl playing with a toy gun as a picture of a boy playing with a toy gun. Children remembered more details and demonstrated less distortion of memory when the stories were consistent with gender schema. This supports the idea that children are actively seeking out information to confirm and develop their gender schema.

A follow-up study was carried out by Martin et al (1995). In this study, four-year-olds were presented with new toys that they would never have seen before and which were gender-neutral. They were then asked what they thought of the toy. After that, they were asked what they thought other boys and girls would think about the toy. Children predicted that same-sex children would like the toys as much as they did and that the other-sex children would not.

Evaluation of Gender Schema Theory

Gender schema theory explains why children’s gender roles do not change after middle childhood. The established gender schemas tend to be maintained because children pay attention to and remember information that is consistent with these schemas.

One limitation of gender schema theory is that the concept of "self-socialization" - that is, that children actively seek out information about their gender, is vague and unmeasurable. The theory also does not help explain children who do not conform to a society's gender norms.

Finally, the theory does not address biological factors. Whenever we look at a single psychological approach without considering the interaction of biological, cognitive and sociocultural factors, this leads to a limited and potentially biased explanation of human behaviour.

ATL: Critical thinking

Watch the following film and then answer the questions below.

Questions

Why do you think that the children react this way?

Do you think that this experience will change the children's perception of gender (social) roles? Why or why not?

Why do you think that the children react this way?

They reacted this way because they have stereotypes about the types of jobs that men and women may hold. They were also primed by asking them to draw the images, so they had reinforced their thinking in their own drawings - so they were surprised to see people that actually contradicted their beliefs.

Do you think that this experience will change the children's perception of gender (social) roles? Why or why not?

Although there is some potential, psychologists argue that they will most likely experience the "discounting effect" - seeing these women as exceptions and therefore not disproving the stereotype that they hold. If you listen carefully to the video, when the women walk in, one of the children says, "They've all dressed up!"

Sociocultural factors

According to social cognitive theory, one reason boys and girls behave differently is that they are treated differently by their parents and others. It is also known that boys and girls are often given different toys and have their rooms decorated differently. Generally, children learn to behave in ways that are rewarded by others and to avoid behaviours that are punished or frowned upon.

According to social cognitive theory, one reason boys and girls behave differently is that they are treated differently by their parents and others. It is also known that boys and girls are often given different toys and have their rooms decorated differently. Generally, children learn to behave in ways that are rewarded by others and to avoid behaviours that are punished or frowned upon.

There are two important factors in social cognitive theory. The first is the presence or absence of reward for gender-appropriate behaviour, and punishment for gender-inappropriate behaviour. The second factor is modelling of behaviour demonstrated by same-sex models. By observing others behaving in particular ways and then imitating that behaviour, children receive positive reinforcement from significant others for behaviour that is considered appropriate for their sex.

Fagot (1978) carried out a series of naturalistic observations of parent/child interactions. Toddlers and their parents were observed in their homes using an observation checklist. The researchers wanted to examine the parental reaction when the behaviour of the child was not "gender appropriate." It was found that parents reacted significantly more favorably to the child when the child was engaged in gender-appropriate behavior and were more likely to give negative responses to "gender inappropriate" behaviors. Fagot and her team followed up by interviewing the parents. The parents' perceptions of their interactions with their children did not correlate with what was observed by the researchers, indicating that this is not a conscious behaviour.

Fagot's research, however, makes some assumptions about the role of parents on gender development. First, it argues that direct tuition - that is, the use of rewards and punishment - will have an effect on the child's gender development. However, since the study was not longitudinal, we do not know if the children whose parents punished them for "gender-inappropriate" behaviour grew up to be more traditional in their gender role. In addition, the assumption that these punishments/rewards alone play a key role in the development of gender identity is reductionist. Social Cognitive Theory would argue that it is also the modeling of behaviour by the parents that would play a role. We also would also have to consider the role of the media and peers. Perhaps Fagot is actually showing us more about how gender stereotypes affect the behaviour of the parents, rather than the gender identify of the child.

Sroufe et al. (1993) observed children around the age of 10 -11 years, and found that those who did not behave in a gender-stereotyped way were the least popular. These studies indicate that children establish a kind of social control in relation to gender roles very early, and it may well be that peer socialization is an important factor in gender development.

Media is an important part of spreading culture. Some studies have found that there is a positive correlation between high television viewing and gender stereotyping, but these studies are only correlational and this leads to the question of bidirectional ambiguity - that is, do gender-biased individuals watch more television, or does watching television make people more gender-biased. Glascock (2001) carried out a content analysis and found that since the 1990s there has been an increase in the number of strong female characters in the media. Although this may account for the change in some women's behaviour, it is difficult to know if the media is affecting change, or whether the media is simply reflecting a changing cultural norm.

Evaluation of sociocultural arguments

A strength of sociocultural explanations of gender identity is that they take into account the social and cultural context in which gender socialization occurs. It predicts that children acquire internal standards for behaviour through reward and punishment - either by personal or vicarious experience. A number of empirical studies support the notion of modeling.

One weakness of sociocultural explanations is that they cannot explain why there seems to be considerable variation in the degree to which individual boys and girls conform to gender role stereotypes. A second limitation is that Social Cognitive Theory suggests that gender is more or less passively acquired. Research actually shows that this is not the case. Children are active participants in the socialization process. Developing gender identity is a rather complex process that involves cognitive processes as well as environmental and biological factors.

Another limitation of Social Cognitive Theory is that, due to the fact that the majority of caregivers are still women, boys and girls have very similar experiences in their development. The theory does not account for this. If, according to Social Cognitive Theory, children learn their gender by imitating a model, then children's gender identity should in most cases be highly influenced by the mother's gender identity. This shows the importance of peers and other socializing factors.

Cultural influences on development of gender roles

Sociocultural arguments help us to understand why gender roles may change over time. This is clearly demonstrated over the past century in the western world, where gender roles have changed steadily. Women have entered the labour market, and in the European Union, around 64 percent of women are employed - compared to 51% in the US and 46% in Australia. Women are entering all kinds of professional fields, although there is still a gender difference in certain areas. A significant cultural change that is being seen is that fathers participate in childcare and have the right to paternal leave. A study by Reinicke et al (2005) showed that young fathers in Denmark say that it is important for them to have close contact with their baby and take part in caring for the child. However, the study is based on interviews with 15 fathers who had taken a relatively long period of paternity leave. It is difficult to know if this is truly an indication of a cultural shift or particular to the participants in this study.

Silva et al (1992) studied Sri Lankan adolescents to see if globalization had an effect on their gender role identity. The researchers found that more than half of the girls in the study saw the ideal woman as being educated and employed, even though the traditional role of Sri Lankan women is a homemaker. This demonstrates that there may be factors outside of the culture - for example, information from the Internet or changing economic demands in a country - that may have a stronger influence on gender roles than the culture itself.

ATL: Inquiry

Until recently, in the West when "gender" was discussed, the meaning was "male" or "female." However, there are several cultures around the world that have a "third gender" - that is, individuals are categorized, either by themselves or by society, as neither man nor woman. Today the West has begun to use the term non-binary to describe this form of gender identity.

Until recently, in the West when "gender" was discussed, the meaning was "male" or "female." However, there are several cultures around the world that have a "third gender" - that is, individuals are categorized, either by themselves or by society, as neither man nor woman. Today the West has begun to use the term non-binary to describe this form of gender identity.

Do some research on third gender identities around the world. Choose one of the cultures below. How is this gender different from the traditional male/female dichotomy? How is it similar to the non-binary concept that is now being recognized in the West?

- Fa'afafine of Samoa and Tonga

- Hijras of India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan

- Kathoey of Thailand

- Sworn virgins of Albania

This activity is done best as a class webquest. Have students investigate each of the following cultural groups and then ask them as a class to discuss how this compares to the Western concept of non-binary.

For each of the groups, I have provided a link that may help students get started with their research.

- Fa'afafine of Samoa and Tonga

- Hijras of India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan

- Kathoey of Thailand

- Sworn virgins of Albania

After they have done some research on the groups, you may want to show them the following video to begin the discussion.

Checking for understanding

The stage in gender identity development when a child realizes that they will not grow up to be the other gender is called

Whiting and Edwards concluded that cultural differences in gender behaviour is the result of

According to the theory of psychosexual differentiation, what is responsible for gender differences?

Money and Erhard argued that

Martin and Halvorson's study showed that a child's gender schema

Which of the following is not true about the social cognitive learning theory of gender identity?

Sroufe's research indicates that the strongest influence on a child's gender development may be

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team