Parker et al (2001)

Parker, Cheah & Roy (2001) carried out a study to determine the extent to which symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder differed between Chinese and Australian patients. You can use this study for the following learning objectives:

Parker, Cheah & Roy (2001) carried out a study to determine the extent to which symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder differed between Chinese and Australian patients. You can use this study for the following learning objectives:

Concepts of normality and abnormality.

Sociocultural factors in diagnosis.

Prevalence of disorders.

The original study is available here.

One of the questions of psychology is whether psychological disorders are universal. Early clinicians argued that since certain symptoms were not observed in different cultures, that disorders were not universal. More modern research argues that the disorders may be universal, but that their symptoms may not be. As early as 1986, Kleinman found that the Chinese tend to somaticize the symptoms of depression - that is, they report bodily symptoms such as headaches, insomnia and back pain, rather than affective symptoms such as sadness or pessimism. Researchers have argued that this may be due to cultural dimensions; in collectivistic societies it is less appropriate to reveal one's emotions, so perhaps the somatization is the way that they communicate mental distress. Others argue that it may be because of the stigma associated with mental illness in Chinese society that leads people to express "appropriate symptoms."

The study by Parker et al was carried out almost 20 years later and found similar results to Kleinman's original study.

To compare the extent to which depressed Chinese patients in Malaysia and Caucasian patients in Australia identified both cognitive aspects of depression and a range of somatic symptoms as a sign of their depression and the reason that they sought professional help.

The sample was made up of 50 Malaysian participants of Chinese heritage and 50 Australian participants of Caucasian, Western heritage. Whereas the Australians all had English as their first language, the Chinese were a mix of Chinese (80%) and English (20%) as their first language. All participants were out-patients who had been diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder, but who did not have other diagnoses as well, such as drug addiction or schizophrenia.

The questionnaire was based on two sets of symptoms. First, a set of mood and cognitive items common in Western diagnostic tools for depression. Secondly, a set of somatic symptoms commonly observed by Singaporean psychiatrists. The questionnaire was translated into Malay and Mandarin Chinese. It was back-translated to establish credibility.

The patients were asked to judge the extent to which they had experienced each of the 39 symptoms in the last week. They had only four options: all the time, most of the time, some of the time and not at all. They were also asked to rank the symptoms that they experienced in order of how distressing they were. Through the assistance of their psychiatrists, it was also noted what the primary symptom was that led to them seeking help.

When looking at which symptom led them to actually seek help, 60% of the Chinese participants identified a somatic symptom, compared to only 13% of the Australian sample.

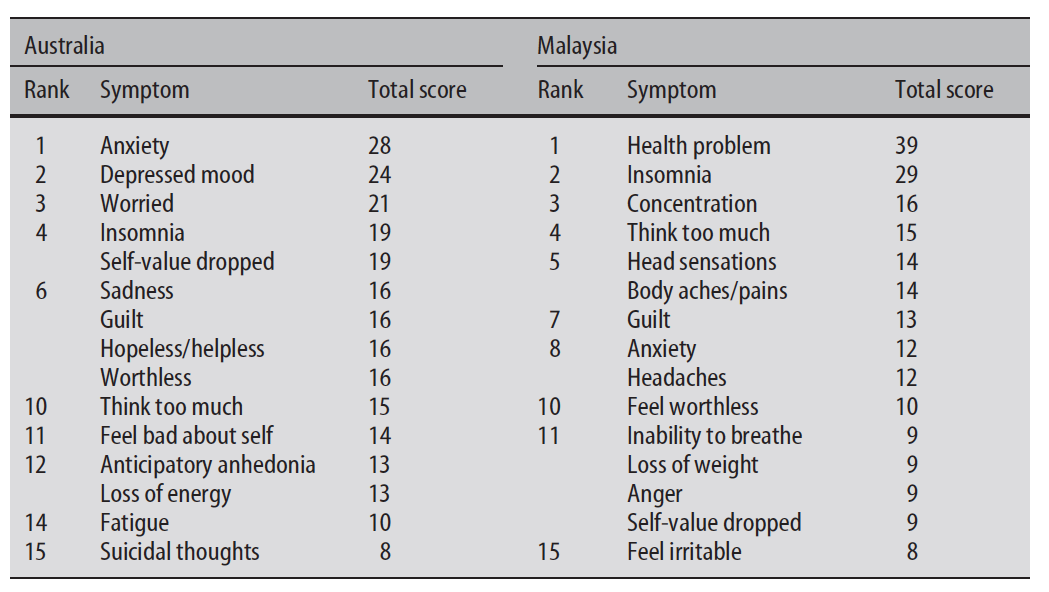

Below you can see how each culture ranked the various symptoms in terms of the amount of distress they cause.

However, when comparing the lists of which symptoms each group acknowledged experiencing, something rather interesting happened. There was no significant difference in the number of somatic symptoms indicated by each group as being linked to their depression. However, the Chinese participants were significantly less likely to identify cognitive or emotional symptoms as part of their problem. They were less likely to rate feeling helpless and hopeless, a depressed mood, having poor concentration, or having thoughts of death than the Australian participants. The role of culture is evident here; in Western culture it is more appropriate to discuss one's emotions and depression is seen as linked to a lack of emotional well being; whereas in Chinese culture, it is less appropriate and even stigmatized if one speaks about a lack of emotional health.

The study attempted to develop a questionnaire based on cultural evidence relevant to the participants. They did not simply use a standardized Western questionnaire that may have influenced the results.

They did choose participants based on the DSM-IV criteria for diagnosing Major Depressive Disorder. In this sense, the study demonstrates an imposed etic approach to research. It may have eliminated people from the sample who may have a form of depression that does not meet the Western criteria for diagnosis; this may account for the similarities in the two samples.

Asking patients to recall their "first symptoms" is open to memory distortion and to demand characteristics. If in the West we believe that depression is an emotional disorder, patients may expect that this is the correct response.

Malaysia is a very modern and Westernized society. The effects of globalization may account for the relatively small difference in the data. Research on more cultures would be necessary to test the reliability of the findings.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team