Biological approach to OCD

The biological approach has two key arguments for the origins of obsessive-compulsive disorder. First, there is research that shows that the disorder may be rooted in the brain. Secondly, there is evidence that OCD may be the result of genetics.

The biological approach has two key arguments for the origins of obsessive-compulsive disorder. First, there is research that shows that the disorder may be rooted in the brain. Secondly, there is evidence that OCD may be the result of genetics.

As you examine biological explanations, you will see that they are both reductionist and deterministic. They are reductionist in that they are trying to explain a complex behaviour by reducing it to a singular biological mechanism.

It should be remembered that although a person’s biological makeup may make them more vulnerable to disorders such as obsessive-compulsive disorders, symptoms may only be expressed under certain environmental circumstances. Deterministic approaches ignore the role of free will, which relates to our unique human potential. However, knowing that one may have a vulnerability to a disorder could potentially allow us to take steps that could prevent or control it.

Linking to Paper 1

When reading through this page, you will see that you can use much of the research here to answer questions on Paper 1. Specifically, the research can be used to answer questions on:

- the localization of brain function;

- the role of individual genes;

- the use of animal research in understanding human behaviour (HL only)

Introduction to biological arguments

Here is the story of David Adam, a journalist and the author of the “The Man Who Couldn't Stop”.

Questions

1. Which parts of the brain seem to be linked to OCD?

The frontal lobe, which has an important role in controlling the basal ganglia.

2. Which neurotransmitters appear to be linked to OCD?

Dopamine may be too active and serotonin too low.

3. Which treatments have been used for OCD?

Anti-depressants, dopamine regulation, talking therapy, and Deep brain stimulation

4. How have mice been used to model OCD in laboratory experiments?

Mice have been bred with a genetic mutation to engage in compulsive behaviours. You can also present animals with situations where they would have to show flexibility in thinking. With animals, we can actually test for causality in a way that would be unethical in humans.

If you would like to continue watching the rest of the program, the second and third parts of this video can be found here.

Localization of function

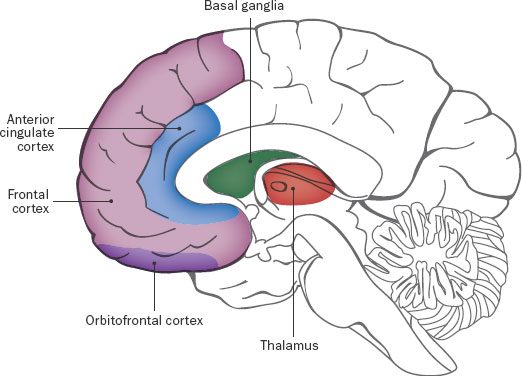

It appears that a specific neural circuit connecting the orbito-frontal cortex (OFC) and the basal ganglia may be responsible for the obsessive and intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviours that characterize OCD. This has become known as the worry circuit.

It appears that a specific neural circuit connecting the orbito-frontal cortex (OFC) and the basal ganglia may be responsible for the obsessive and intrusive thoughts and compulsive behaviours that characterize OCD. This has become known as the worry circuit.

The OFC has been shown to be associated with decision-making, yet research also shows that it is linked to urges for sex, aggression, and bodily excretion. This helps explain why this brain region may be linked to overwhelming drives to enact certain behaviours over which people feel they have no control.

The worry circuit links the OFC and a region called the caudate nucleus, which is part of the basal ganglia. This region sends the strongest impulses to the thalamus, which triggers further thinking about these impulses. A series of behaviours may then be conducted, thus reducing the impulse - for example, washing our hands if we feel we might have touched something contaminated to help us to feel clean and reduce anxiety. Generally speaking, the caudate nucleus is associated with the initiation and subsequent inhibition of movements, especially those that result in positive outcomes. It is also involved with cognition, emotion, attention, and habit formation.

A dysfunction in this circuit has been proposed as an explanation of OCD, where behaviours linked to certain urges or impulses fail to reduce the urge, and even seem to reinforce it - for example, triggering repetitive sequences of behaviors, such as checking that electrical appliances are switched off or that doors are locked over and over again.

Thus, overactivity in the neural pathway connecting the OFC and caudate nucleus could trigger compulsive behaviour. Abnormalities of the caudate nucleus could mean that once initiated, goal-directed behaviour fails to be inhibited, leading to relentless cycles of compulsive behaviour.

One strength of this neurological explanation of compulsive behaviour is that it is supported by research evidence.

For example, Thobois et al. (2004) conducted a case study on a man who underwent brain surgery for a blood clot on his caudate nucleus, and subsequently suffered from compulsions but without obsessive thinking.

This study provides important evidence for the localization of repetitive behaviour to the caudate nucleus, as the patient experienced no such behaviour before the surgery.

Key study: Thobois et al (2004)

Thobois et al (2004) carried out a case study of a 24-year-old male who underwent surgery to remove a hematoma in the region of the caudate nucleus in the basal ganglia.

Thobois et al (2004) carried out a case study of a 24-year-old male who underwent surgery to remove a hematoma in the region of the caudate nucleus in the basal ganglia.

Three months after the surgery, the patient developed compulsive behaviours, but no obsessive thoughts. He couldn't stop himself from only using words and sentences of 10 letters. In addition, he became more aggressive. His symptoms had a significant impact on his work and social relationships. He spent between 30 minutes and 2 hours a day on his compulsive behaviours and felt that the behaviours were outside his control.

Thobois and his team carried out a series of psychological tests, including the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive (YBOC) scale. They concluded that the damage to the caudate nucleus played a significant role in the onset of the disorder.

The research by Thobois et al (2004) has been supported by other case studies. Katz and Flemming (2014) reported the case of a 31-year-old woman with lesions on the caudate nucleus, also caused by internal bleeding. She developed an obsession with germs and contamination that required hospitalization. She was successfully treated by a combination of behavioural therapy and medication.

Gillian et al (2014) carried out a quasi-experiment with both patients with OCD and a control group. Both groups received fMRI scans while they were asked to press a pedal to avoid shock to the wrist over an extended time. In the final stage of testing, the shock block was removed to assess whether the pedal-pressing behaviors of the patients could be discontinued.

The researchers found that patients with OCD were less capable of stopping their pedal-pressing habits than the control group. In addition, individuals in the OCD cohort were more likely to have hyperactivation in the caudate nucleus after the shock block was removed, compared with those without OCD.

Although the physiology of the worry circuit is fairly well understood, the reason why people develop abnormalities in this region is still open to debate. As these pathways are rich in serotonin receptors, it has been argued that deficiencies of this neurotransmitter may be responsible and this may result from both genetic and environmental factors. For example, serotonin production is inhibited by high levels of the stress hormone cortisol, helping to explain why traumatic life events may trigger OCD-like symptoms. Yet such explanations are arguably over-simplified; many people who have faced such life events do not develop symptoms, and this is no doubt mediated by protective factors including social support and biochemical factors that underpin resilience.

Genetic explanations of OCD

Early studies of OCD were often family studies. These studies found that OCD tends to run in families. Pauls et al. (1995) found that first-degree relatives of a person with OCD are almost five times more likely to also have the same disorder, although the risk diminishes with advancing age since OCD generally has a fairly young age of onset.

Carey and Gottesman (1981) suggest that OCD may be one of the most heritable disorders. Their study, which looked at 30 twin samples, found a concordance rate of 87% for monozygotic twins compared with 47% for dizygotic twins. Follow-up studies have consistently found monozygotic twins to have higher concordance rates for OCD and obsessive-compulsive symptoms than dizygotic twins, confirming an important genetic contribution to OCD. Monzani et al (2014), the largest and most statistically robust twin study to date (5409 female twins), found a monozygotic twin concordance rate of 0.52 and a dizygotic concordance rate of 0.21, with overall heritability for OCD estimated to be 48%.

Critical thinking about research

As early as the 1930s, researchers began to recognize the potential role of genetics in what was then called ‘obsessive neurosis’. Aubrey Lewis (1936) studied 50 patients from the Maudsley Hospital in London. 37% had at least one parent with the same disorder and 22% had a sibling with the disorder.

As early as the 1930s, researchers began to recognize the potential role of genetics in what was then called ‘obsessive neurosis’. Aubrey Lewis (1936) studied 50 patients from the Maudsley Hospital in London. 37% had at least one parent with the same disorder and 22% had a sibling with the disorder.

What are the potential limitations of using family studies (a.ka. pedigree or kinship studies) as support for the role of genetics in OCD?

Limitations of family studies include:

- When family members live together in the same household, they may be exposed to the same environmental stresses and challenges. If they exhibit similar symptoms, this may be the result of environmental factors, rather than biological ones.

- Family members that live together may also model abnormal behaviour to each other, meaning that such behaviours are adopted through the process of social learning as opposed to being the result of shared genes.

- They are often based on the assumption that diagnoses are valid. In addition, when thinking about grandparents or deceased members of the family, information is anecdotal and it may not be possible to verify it.

- Family studies do not identify a specific gene - they simply look for behavioural trends within a family.

Candidate genes

As many as 230 genes have been linked to OCD, making it a polygenic disorder. As noted above, both serotonin and dopamine may be linked in some way to OCD. The enzyme which breaks down dopamine is called catechol-O-methyltransferase [COMT] and the gene that codes for this enzyme is called the COMT gene. Karayiorgou et al. 1997 identified a specific version of this gene called the ‘low activity’ allele which is more common in people with OCD. Low levels of this enzyme could lead to a buildup of dopamine in the synapse, which could be linked to the repetitive behaviour cycles common to people with OCD.

Another set of genes that have been the focus of more recent attention are the SLITRK genes - which are responsible for synapse regulation. Specifically, the SLITRK5 gene plays an important role in learning from our experiences as it has links with neuronal growth and neuroplasticity. This gene is involved in coordinating processes controlled by BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) which is essential to the healthy growth and function of our neural networks.

In terms of practical applications of genetic explanations of OCD, research on the role of the SLITRK family of genes suggest that treatment designed to increase BDNF may be beneficial for people with OCD. Diet, exercise, time spent with others, and even being outdoors in the sunshine have all been shown to increase this essential brain chemical.

One strength of the genetic explanation of compulsive behaviour is that there is strong support from animal experiments such as Schmelkov et al. (2010).

Key study: Shmelkov et al (2010)

The video explains how SLIRK5 may be linked to OCD in a study using mice. The study raises interesting scientific and ethical questions and could be used to discuss the insight that can be provided into human behaviour, through the use of animal models. (Paper 1 Biological Approach Higher Level Extension).

Although having certain genes may make one vulnerable to a disorder, environmental experiences, especially those linked to chronic stress and trauma, have a central role to play in gene expression. This means that OCD may result from an interaction between genetic vulnerability and a person’s life experiences. For example, Timpano et al. (2007) found that 54% of a sample of 265 people living with OCD had experienced at least one traumatic life event and there was a positive correlation between the number of such events and the severity of symptoms. However, the study demonstrated that people who exhibited compulsive checking and obsessions with order were most likely to have experienced traumatic life events than other types of compulsions.

Strengths

- Genetic studies as well as case studies of brain damage have been consistent, establishing the reliability of the findings.

- Modern research has allowed us to actually locate genetic variations using very large sample sizes

- Modern research recognizes the interaction of environmental and biological factors and does not use a solely reductionist approach.

Limitations

- Correlational studies do not establish a cause and effect relationship.

- Animal models may give insights into compulsions, but obsessive thoughts cannot be observed or measured.

- It is impossible to isolate variables and separate out social factors in twin studies.

- Genetic arguments do not account for the variations in symptomology in different cultures.

- The Treatment Aetiology Fallacy – that is, the mistaken notion that the success of a given treatment reveals the cause of the disorder.

Checking for understanding

Abnormalities of which brain region have been implicated as a cause of OCD?

The fact that other case studies also support the role of the caudate nucleus in the acquisition of OCD symptoms, makes the Thobois’s findings more…

Although Gillian et al. (2014) took a more experimental approach to studying the role of the caudate nucleus, the study lacks

Which neurotransmitter is abundant in the worry circuit pathways?

Which hormone inhibits serotonergic activity in the brain and may explain why OCD can be triggered by stressful life events?

How many times more likely are you to develop OCD if a first degree relative also has the disorder?

Monzani et al. (2014) have recently suggested the heritability of OCD to be….

A variation of the COMT gene has been linked with OCD and this means OCD could result from…

One advantage of animal research such as Schmelkov’s study of the SLITRK5 gene in mice is that…

Traumatic life events are more common in people with which type of OCD symptoms?

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team