Hilliard and Liben (2010)

Social Identity Theory can be used to explain the formation of stereotypes. The following study by Hilliard and Liben looks at how social category salience can lead to the development of stereotypes of the "out-group."

Social Identity Theory can be used to explain the formation of stereotypes. The following study by Hilliard and Liben looks at how social category salience can lead to the development of stereotypes of the "out-group."

This study could also be used to explain gender role development as well as the enculturation of gender roles.

Social Identity Theory argues that by categorizing ourselves into in-groups and out-groups, we then begin to see the members of outgroups as more similar to each other than they actually are. Out-group homogeneity then makes it easy for us to apply stereotypes to the members of the groups without having to consider whether the characteristics are actually true of a particular individual. In addition, since we do not usually interact with the out-group as much as with our in-group, we learn very little about their traits and are more likely to maintain stereotypes.

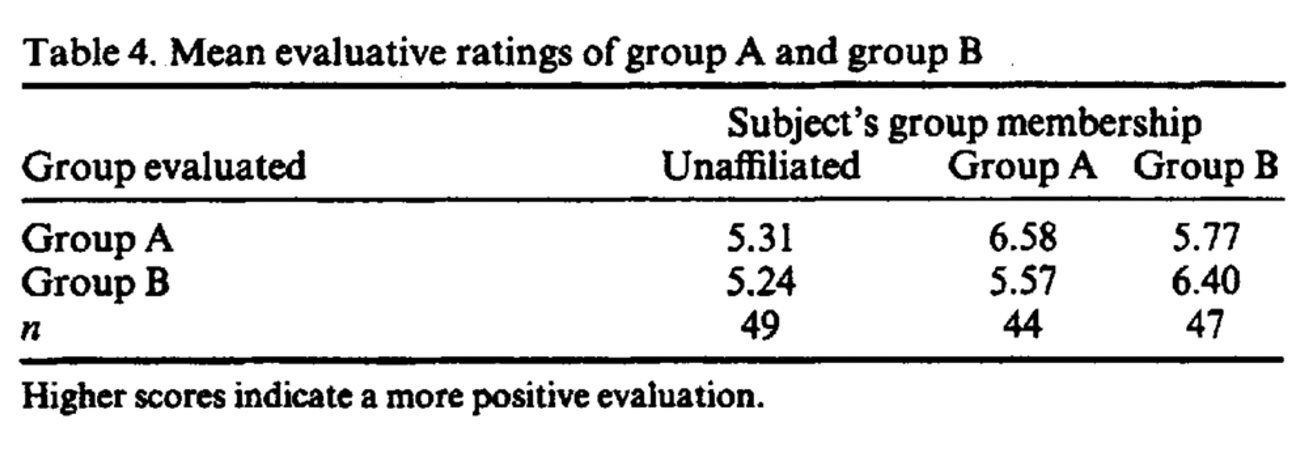

Schaller (1991) carried out a study of 141 introductory psychology students in which participants were randomly assigned to be members of a group. They were either told that they were in "group A", "Group B" or they were in a control group with no group categorization. They were also told that there were more people in group A than in group B. They were then given a booklet with a series of statements that described members in both the group to which they had been assigned and the group that was not their group. There was an equal number of positive and negative statements about each group. They were then given a list of traits and asked to rank each group on a 10 point scale. The results are seen in the table below:

You can see that each group tended to rate their in-group as more positive. The control group (unaffiliated) did not have a significant difference in its rating of groups A and B.

In another study, Linville and Jones (1980) gave participants a list of traits and asked them to think about either members of their own group (e.g., African-Americans) or members of another group (e.g., European Americans) and to place the traits into piles that represented different types of people in the group. The results of these studies showed that people perceive out-groups as more homogeneous than their ingroup. African Americans used fewer piles of traits to describe European Americans than African-Americans, young people used fewer piles of traits to describe elderly people than they did young people, and students used fewer piles for members of other universities than they did for members of their own university.

Although both of these studies have high levels of internal validity, they are both rather artificial tasks. What would happen if we tried to study the role of SIT in a naturalistic environment? This was the research done by Hilliard and Liben (2010).

Hilliard and Liben carried out an experimental study to determine how social category salience may play a role on the development of stereotypes and inter-group behaviour in elementary school children.

The study took place at two preschools. The participants were 57 US children ranging from 3 years 1 month to 5 years 6 months. Each school had a roughly equal number of male and female children.

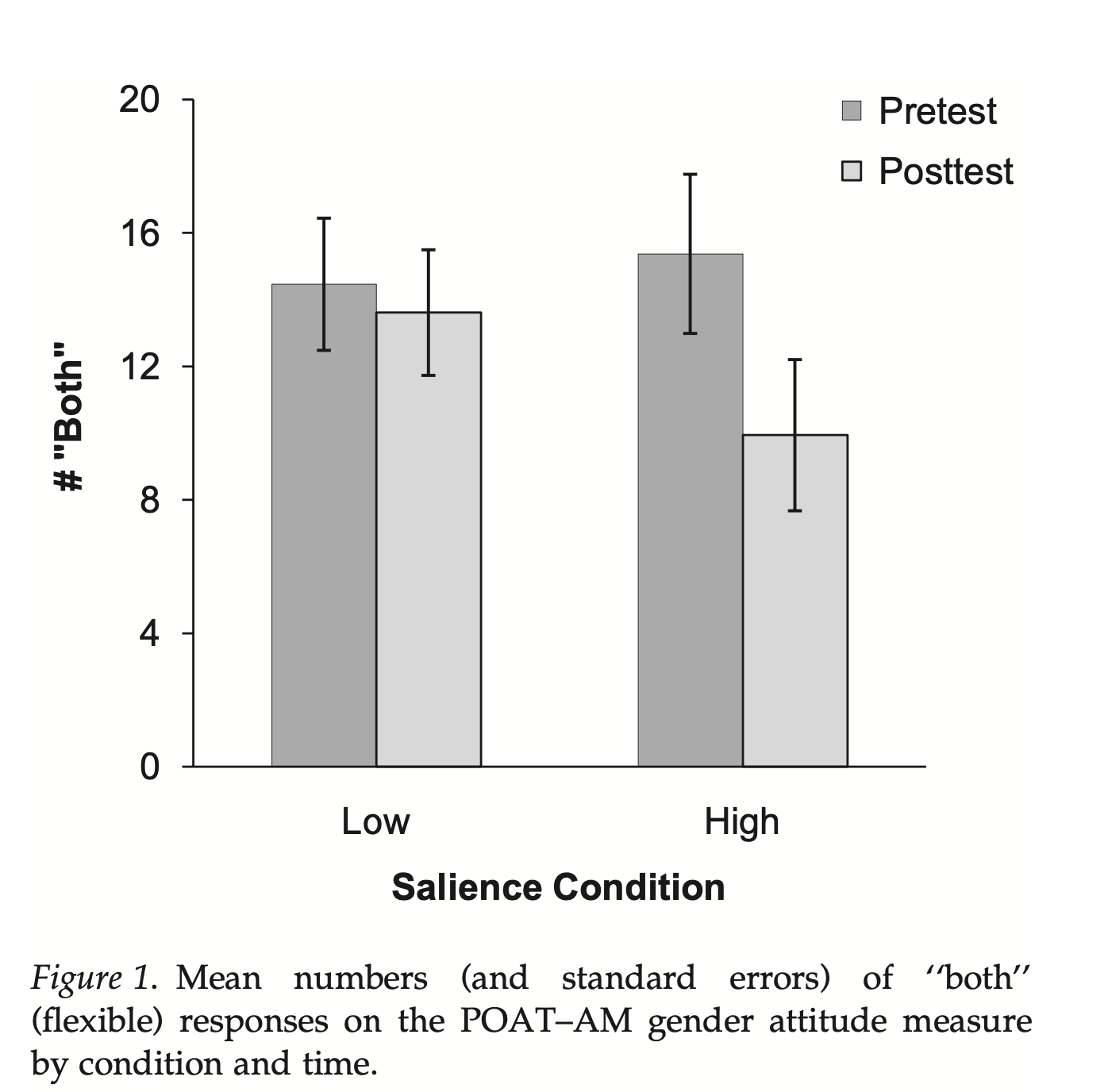

The study used a pre-test/post-test design. To begin, each child completed a gender attitude test (POAT-AM) to measure their “gender flexibility.” They were shown pictures of activities or occupations, and for each item asked if boys, girls, or both boys and girls ‘‘should’’ perform it. The test included 22 culturally masculine (e.g, be a firefighter), 20 culturally feminine (e.g., play with dolls), and 24 neutral (e.g., fly a kite) items by pointing to one of three cards to show who they believed should do the activity. The test calculated the number of ‘‘both men and women’’ responses. Lower numbers of ‘‘both’’ responses indicate a higher number of gender stereotypes.

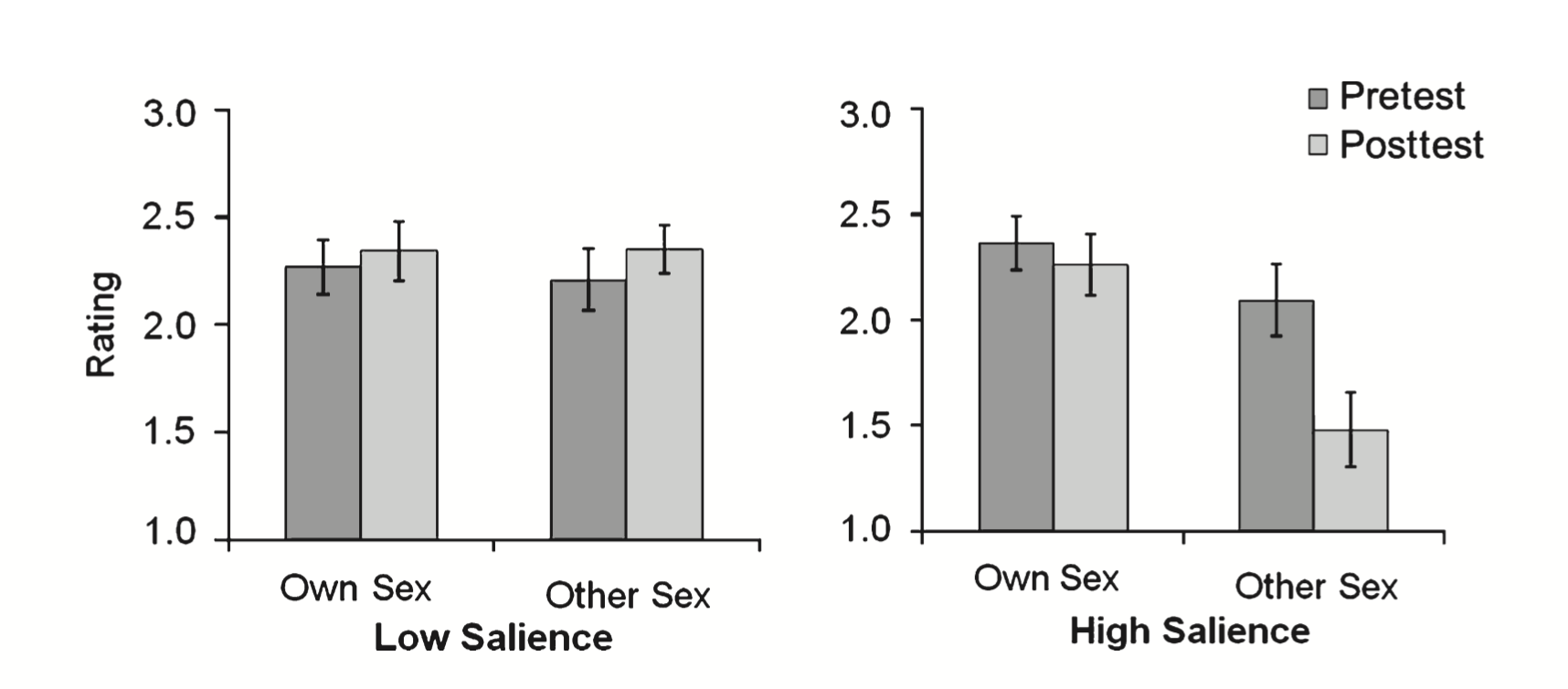

A second measure was taken by observing their play to determine to what extent they played with same-sex vs opposite-sex peers.

The schools were randomly allocated to one of two conditions.

The high salience condition: Children were made aware of their gender by having them line up by sex, posting separate boys’ and girls’ bulletin boards, and the teachers’ use of gender-specific language (e.g., ‘‘I need a girl to pass out the markers’’ and ‘‘Good morning boys and girls’’). Teachers were instructed not to set up competitive activities between the boys and girls.

Low salience condition: Teachers were given no instructions about changing their behavior. This served as the control group.

It is important to note that in both preschools, it was the policy to avoid gendered language. Children in both conditions had experienced similar classroom environments prior to the study.

The study lasted for two weeks. The results can be seen below.

In this first graph, you can see that in the pre-test, both groups had a similar number of "both" responses when looking at images of activities/occupations on the POAT-AM gender attitude test. However, after the two-weeks of high gender salience, there was a significant decrease in the number of "boths" - meaning that the children had more gender stereotypes.

In the graph below, you can see how the amount of time playing with the opposite gender changed over a period of two weeks. In the low salience condition, there is no significant change. However, in the high gender salience condition, play with the "out-group" decreased significantly.

After two weeks, children in the high salience condition showed significantly increased gender stereotypes and decreased play with other-sex peers.

After the study, the children participated in a debriefing program administered by both teachers and experimenters. This debriefing program was included in an effort to counteract any possible increase in stereotyping and to help children understand prejudice and stereotypes.

The study was experimental - that is, an independent variable was manipulated and more than one dependent variable was measured. This was also done in the children's natural environment. The study is a field experiment. The study has high ecological validity, but since the environment cannot be strictly controlled, the study has low internal validity.

The study suffers from sampling bias. The preschool in this study was not free. So, the participants are most likely middle to upper-class children. In addition, the preschools had a policy of gender neutrality in the classroom. This was perfect for the experiment, but this means that the parents of these children were most likely of a certain education level as well as shared a set of values. This may make it more difficult to generalize the findings beyond the sample.

The study does indicate a cause and effect relationship, but it is not really possible to measure the child's level of salience, even though the study set up situations in which this was the goal.

Although the study did use the debriefing to counteract any negative effects of the two-week experiment, there are ethical concerns about undue harm to the children; that is, it may not be possible to reverse their newly developed behaviours.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team