Evaluating experiments

Psychologists often use experiments because they are a way to establish a cause and effect relationship. This is done by manipulating an independent variable and measuring the effect on a dependent variable while attempting to control other variables that could influence the outcome.

Psychologists often use experiments because they are a way to establish a cause and effect relationship. This is done by manipulating an independent variable and measuring the effect on a dependent variable while attempting to control other variables that could influence the outcome.

One of the limitations of an experiment could be that a variable was not controlled. A variable that influences the results of an experiment is called an extraneous variable.

An example of an extraneous variable could be a trait of a participant that was not controlled for. If I am testing to see if music has an effect on one's ability to recall a list of 20 words, but I didn't check to see if all were native English speakers, then the fact that in one group I had significantly more non-native speakers could be a confounding variable. Extraneous variables can also be with the materials in the study. For example, it may be that the words were all one-syllable, which may have made them more easily recallable. This could then be seen as an extraneous variable that may have affected the results, rather than the IV that I was manipulating - that is, listening to music.

Failure to control for extraneous (confounding) variables means that the internal validity of a study is compromised - that is, we cannot be sure that the study actually tested what it claims to test and the results may not actually demonstrate a link between the independent and dependent variable.

Methodological considerations

Methodological considerations have to do with the design and procedure of the experiment. Discussing methodological considerations is one of the key evaluative strategies when discussing research.

One concern that researchers have is what is called participant biases - or demand characteristics. This is when participants form an interpretation of the aim of the researcher's study and either subconsciously or consciously change their behavior to fit that interpretation. This is more common in a repeated measures design where the participants are asked to take part in more than one condition of the independent variable. However, it may also occur in an independent samples design. Participant biases are also a problem in observations and interviews.

There are at least four different types of participant biases.

Expectancy effect is when a participant acts a certain way because he wants to do what the researcher asks. This is a form of compliance - the participant is doing what he or she is expected to do. Often, simply knowing that you are in an experiment makes you more likely to do something that you would never do in normal life. And this is where experiments can be problematic.

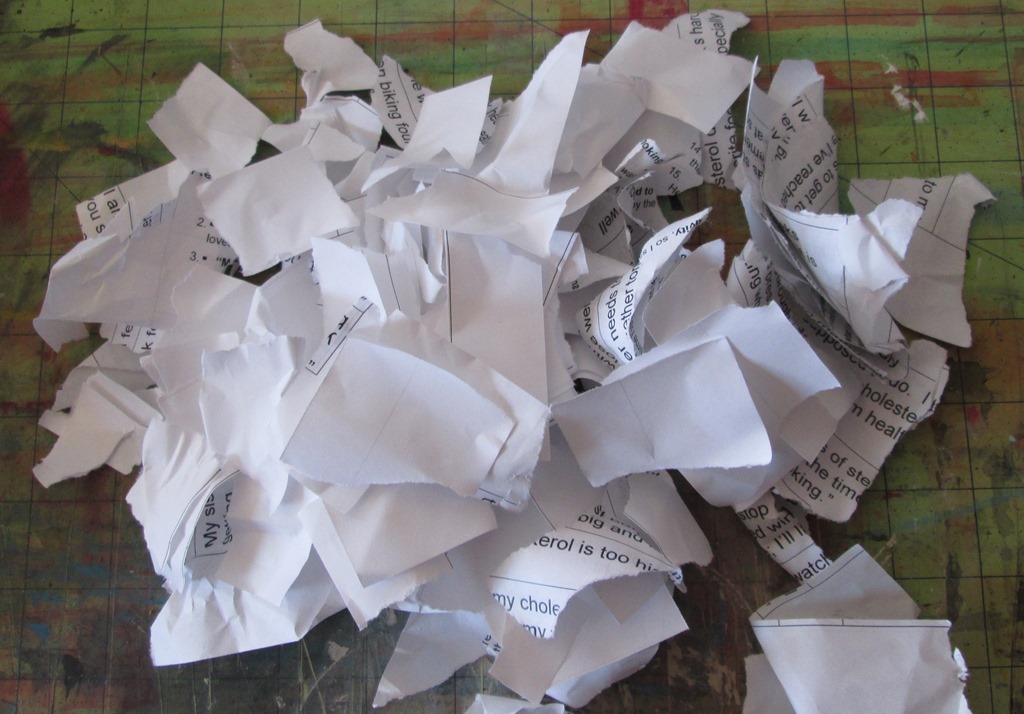

Orne (1962) carried out a simple study to test the effect of demand characteristics. Participants were asked to write solve addition problems of random numbers. There were 224 numbers per page. Each time they completed a page, they were asked to tear up the sheet into at least 32 pieces and then move on to the next page in the pile. There were 2000 sheets of paper in the pile. The researcher told them to keep working until they were told to stop. In spite of how boring the task was - as well as how useless the task obviously was - the participants continued for several hours because they were "doing an experiment."

Orne (1962) carried out a simple study to test the effect of demand characteristics. Participants were asked to write solve addition problems of random numbers. There were 224 numbers per page. Each time they completed a page, they were asked to tear up the sheet into at least 32 pieces and then move on to the next page in the pile. There were 2000 sheets of paper in the pile. The researcher told them to keep working until they were told to stop. In spite of how boring the task was - as well as how useless the task obviously was - the participants continued for several hours because they were "doing an experiment."

Not everyone who "figures out" an experiment will try to please a researcher. The screw you effect occurs when a participant attempts to figure out the researcher's hypotheses, but only in order to destroy the credibility of the study. Although this is not so common, there are certain types of sampling techniques that are more likely to lead to this demand characteristic. For example, if you are using an opportunity sample made up of students who give consent, but feel that there was undue pressure on them to take part, then the screw you effect is more likely. This may be the case when professors at university require students to take part in studies to meet course requirements - or even in your internal assessment... The screw you effect may also happen when the researcher comes across as arrogant or condescending in some way and the participants then decide to mess up the results. Hopefully, this will never happen to you....

Participants usually act in a way that protects their sense of self-esteem. This may lead to the social desirability effect. This is when participants react in a certain way because they feel that this is the "socially acceptable" thing to do - and they know that they are being observed. This may make helping behaviour more likely; or in an interview to determine levels of prejudice and stereotyping, participants may give "ideal" answers to look good, rather than express their actual opinion.s

Finally, sometimes participants simply act differently because they are being observed. This is a phenomenon known as reactivity. The change may be positive or negative depending on the situation. In an experiment on problem solving, a participant may be very anxious, knowing that he is being watched and then make more mistakes than he usually would under normal situations. You can probably imagine that reactivity plays a significant role in interviews - especially clinical interviews - where the interviewee may demonstrate anxiety, overconfidence or paranoia as a result of being observed.

Controlling for demand characteristics

1. Use an independent samples design. By not being exposed to both conditions, participants are less likely to figure out the goal of the experiment.

2. During the debriefing, be sure to ask the participants if they know what was being tested. If they answer yes, this may have an influence on the results.

3. Deception is often used in experiments in order to avoid demand characteristics; however, this may lead to ethical problems if the deception leads to undue stress or harm of the participant.

Another limitation of experiments is what is called order effects. Order effects are changes in participants' responses that result from the order (e.g., first, second, third) in which the experimental conditions are presented to them. This is a limitation of a repeated measures design; for example, testing to see if music affects one's ability to memorize a list of words and the participants are exposed to a series of different types of music.

Another limitation of experiments is what is called order effects. Order effects are changes in participants' responses that result from the order (e.g., first, second, third) in which the experimental conditions are presented to them. This is a limitation of a repeated measures design; for example, testing to see if music affects one's ability to memorize a list of words and the participants are exposed to a series of different types of music.

There are three common order effects that affect the results of a study.

First, there are fatigue effects. This is simply the fact that when asked to take part in several conditions of the same experiment, participants may get tired or they may get bored. In either case, they may lose motivation to try their best or their concentration may be impaired, influencing the results.

One of the limitations of the proposed "effects of different types of music on learning a list of words" study is called interference effects. This is when the fact that you have taken part in one condition affects your ability to take part in the next condition. For example, in an experiment you are asked to memorize a list of twenty words in silence. Now, with music playing, you are asked to memorize a different list of words. The researcher may find that some of the words on the list may be the same as those on the first list. This is an example of an interference effect influencing your final results.

Finally, when we ask participants to do a task repeatedly, we may see that they improve as a result of practice effect. For example, if I want to see how long it takes participants to solve a SUDUKO puzzle under different conditions, it is possible that they are faster in later conditions because they are simply getting better at doing the puzzles because of the practice effect.

Controlling for order effects

1. One control is called counter-balancing. This is when you vary the order in which the conditions are tested. For example, in condition A, participants are asked to recall a list of twenty words without music. In condition B, they are tested with music. Participants are randomly allocated to group 1 or 2. Although this is still a repeated measures design, group 1 is tested first with condition A and then condition B. In group 2, they are tested first with condition B and then with condition A. If order effects did not play a role in the research, then the results should be the same for both groups.

2. There needs to be a long enough pause between conditions.

3. Often researchers use a filler task in order to clear the "mental palette" of the participants. This controls for interference effects. For example, after being shown the first list of words without music, the participants are asked to recall as many words as possible. The researcher then has the participants count backwards by 3 from 100. Then the second condition is administered.

Another methodological consideration is the influence of researcher biases on the results of a study. Researcher bias is when the beliefs or opinions of the researcher influence the outcomes or conclusions of the research. There are several ways that this may occur.

First, there is the problem of confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is when a researcher searches for or interprets information in a way that confirms a preexisting belief or hypothesis. For example, if a researcher is observing children on a playground and believes that boys are more aggressive than girls, the researcher may record more examples of such aggression and not pay attention to aggressive female behaviour.

Another form of researcher bias is the questionable practice of p-hacking. This is when a researcher tries to find patterns in their collected data that can be presented as statistically significant, without first positing a specific hypothesis. For example, I am doing a study of the effect of music on the ability to memorize a list of words. The original plan was that I would have participants listen to different types of music and compare them to silence. However, the study demonstrated no significant data. However, if I apply data to a range of different potential combinations of variables, I finally find: Participants who listened to Moravian folk music recalled significantly more words than those that listened to hip-hop at p ≤ 0.05. However, the study was not designed to test any difference between these two variables, and so there is a concern about the validity of the results.

Another question which should be asked is - who funded the study? It is possible that study you are reading demonstrates funding bias. There is also the problem in psychology that often only studies with results are published. This leads to what is referred to as publication bias.

The problem of funding bias

Although it is tempting to always accuse any study funded by a drug company, government or corporation as being biased, it is important that we can actually establish that the study was biased. After all, funding for research has to come from somewhere. One specific instance of bias that should always raise a red flag is when a drug company or corporation carries out a meta-analysis.

Although it is tempting to always accuse any study funded by a drug company, government or corporation as being biased, it is important that we can actually establish that the study was biased. After all, funding for research has to come from somewhere. One specific instance of bias that should always raise a red flag is when a drug company or corporation carries out a meta-analysis.

In a study by Ebrahim et al (2016), the researchers wanted to measure the extent to which funding bias would affect meta-analyses of anti-depressant drug studies. The researchers looked at 185 meta-analyses evaluating antidepressants for depression published between January 2007 and March 2014. They found that 29% of the meta-analyses had authors who were employees of the assessed drug manufacturer, and 79% had sponsorship or authors who were related to a drug company. Only 31% of the meta-analyses drew negative conclusions about anti-depressant drugs. Meta-analyses done by a employee of a drug company that produced the assessed drug were 22 times less likely to have negative statements about the drug than other meta-analyses.

Controlling for researcher biases

1. Researchers should decide on a hypothesis before carrying out their research. They should not go back and adjust their research hypothesis in response to their results, but instead run another experiment to test the new hypothesis.

2. To control for confirmation bias, researchers can use researcher triangulation to improve inter-rater reliability. As a researcher, I work as a team where we are all observing the children on the playground. If we all observe the same level of aggression in males and females, it is likely that we have avoided confirmation bias.

3. A double-blind control is the standard control for researcher bias. In a double-blind control, the participants are randomly allocated to an experimental and a control group. The participants are not aware which group they are in. In addition, a third party knows which participants received which treatment - so the researcher who will examine and interpret the data does not who received which treatment.

Finally, there are other ways that the validity of a study may be compromised, besides the effect of confounding variables.

Internal validity may also be affected by the construct validity of a study - that is, investigating if the measure really is measuring the theoretical construct it is suppose to be. This has to do with the operationalization of the variables. If you are doing a study of attitudes of Europeans about Americans, asking them if they watch US films, own an iPhone, watch CNN or wear American designer clothes would not be a good measure of "pro-American attitudes." There are several problematic constructs in psychology - including intelligence, communication, love and aggression.

Internal validity may also be affected by the construct validity of a study - that is, investigating if the measure really is measuring the theoretical construct it is suppose to be. This has to do with the operationalization of the variables. If you are doing a study of attitudes of Europeans about Americans, asking them if they watch US films, own an iPhone, watch CNN or wear American designer clothes would not be a good measure of "pro-American attitudes." There are several problematic constructs in psychology - including intelligence, communication, love and aggression.

It is also important to discuss the external validity of a study. External validity is the extent to which the results of a study can be generalized to other situations and to other people. There are two key ways of assessing external validity. One is to determine whether the sample is biased. If the sample is not representative of the population that it is drawn from, then the results are not generalizable to that population and the study lacks external validity. This is also known as population validity.

The second way in which external validity can be assessed is to consider the ecological validity of a study. The basic question that ecological validity asks is: can the results of this study be generalized beyond this situation? Often in laboratories the situation is so highly controlled, it does not reflect what happens in real life - so, we cannot say that it would predict what would happen under normal circumstances and lacks ecological validity. It can also be that the situation was so artificial that it does not represent what usually happens in real life - for example, being asked to shock a stranger in a lab situation or watching a video of a car crash rather than actually observing one in real life.

Finally, whenever we discuss research we should always consider the ethics of the experiment. When researchers do not follow ethical protocols, the research cannot be (or should not be) replicated. This means that the results cannot be shown to be reliable.

ATL: Thinking critically

Please read the following study. Do you think that we can trust the results of this study? Use the vocabulary above when discussing the limitations of the study.

A researcher was interested in the effects of alcohol on perceptions of physical attractiveness of the opposite sex. To study this, he used students from two of his classes, a senior seminar for psychology majors which met one evening a week from 6 - 9pm, and a freshman introductory psychology class, which met two mornings a week at 10 am.

A researcher was interested in the effects of alcohol on perceptions of physical attractiveness of the opposite sex. To study this, he used students from two of his classes, a senior seminar for psychology majors which met one evening a week from 6 - 9pm, and a freshman introductory psychology class, which met two mornings a week at 10 am.

Because the seniors were all at least 21 and thus legally able to drink in the USA, he assigned them all to the condition that received 6 ounces (2 deciliters) of alcohol mixed in with 20 ounces (6 deciliters) of orange juice. The freshman were assigned to the “placebo” alcohol condition, in which they received 6 ounces (2 deciliters) of tonic water (which tastes like alcohol) mixed in 20 ounces (6 deciliters) of orange juice. However, they believed that they were really being served alcohol as part of the psychological study.

Students were invited to participate in the study if they had a free hour after their class with the professor. The professor conducted the study on a Thursday, on a day when the introductory class had an exam. Students drank either the “alcohol” or the placebo drink, waited 30 minutes in a lounge for the alcohol to take effect, and then sat at a computer and performed a five-minute task in which they rated various faces of the opposite sex on physical attractiveness.

The group that had received alcohol rated the faces as more attractive than the group that did not receive alcohol and the professor concluded that alcohol makes people of the opposite sex appear more attractive.

Potential limitations of the study

- The participants are not randomly allocated to conditions.

- There is a sampling bias as all of the participants are students and they are all young. They may not reflect the behaviours of older people.

- There are potential confounding variables. The students take the test at different times of the day. The seniors take it after a test - when they may be sleep deprived and thus the alcohol may have a greater influence on their behaviour. There is also no control on the drinking habits of the students. This may play a role in the influence of alcohol in the experimental group.

- There is a chance that the students in the younger group will guess the goal of the experiment. In the US it is illegal to serve alcohol to minors. Although some may think (wrongly) that is "ok" in the name of science, others may figure it out and then either play along (expectancy effect) or intentionally screw up the experiment because they were hoping for a free drink (screw you effect).

- The researcher has deceived the participants in the placebo group. This is an ethical problem.

- Finally, rating the attraction of an image on a computer is very different from rating attractiveness in real life. This study lacks ecological validity and thus external validity.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team