Rosmarin et al (2010)

The following study can be used to support the socio-cultural explanation of OCD, specifically the role of religiosity with regard to scrupulosity.

The following study can be used to support the socio-cultural explanation of OCD, specifically the role of religiosity with regard to scrupulosity.

This study focuses on Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jews. It is an interesting study as the results are not as the researchers initially expected.

Scrupulosity involves intrusive, blasphemous thoughts and imagery, leading to obsessive fears of punishment, e.g. going to Hell. Compulsions may involve repetitive prayer, excessive confession and reassurance-seeking from religious authorities, and avoidance of situations that might lead to sinful behaviour.

Research has shown that scrupulosity is often resistant to treatments that are effective in reducing symptoms in non-religious type OCD, making this an important area for further study. Given that up to a third of people with OCD are affected by some religious-oriented symptoms, it is critical that new treatment pathways are explored. In some highly religious populations, this figure is much higher.

It has been suggested that scrupulosity is particularly resistant to treatment due to the way other people in the person’s in-group respond to them; they may be commended for their dedication, thus reinforcing their behaviour yet further. Also, such behaviours may be normalized in the community and not seen as a cause for concern. This may make people less likely to seek help from secular mental health practitioners and fail to engage fully with therapy when they do. The researchers suggest that if there is evidence to support this assertion, then it may be helpful to raise awareness of the condition within the affected communities.

The study aimed to examine whether Orthodox Jewish people recognize scrupulosity as a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder. It was hypothesized that since Orthodox Jews value more rigid adherence to the religious texts and rituals than non-Orthodox Jews, they may be less willing to label scrupulosity as a type of OCD or seek help outside of the religious community.

It was predicted that non-Orthodox Jews would be equally likely to label symptoms as OCD and recommend treatment by a mental health practitioner, regardless of whether the symptoms were of a religious nature or not.

The study was an experiment using an independent samples design. 70 Orthodox and 23 non-Orthodox Jews were randomly allocated to one of two conditions. In the experimental condition, they read a vignette describing a 19-year-old man with moderate to severe symptoms of a religious nature - relating to prayer and rituals. The control group read about a similar character who was obsessed with safety and engaged in compulsive checking. Thus, the IV was whether the OCD symptoms were of a religious nature or not.

The dependent variables were the participants’ thoughts about how likely it was that the person in the vignette had OCD and if they showed the behaviours shown by the person in the vignette, the likelihood of seeking professional help from a therapist rather than a religious leader. The participants' religiosity was also measured by a questionnaire about the frequency of prayer and synagogue attendance.

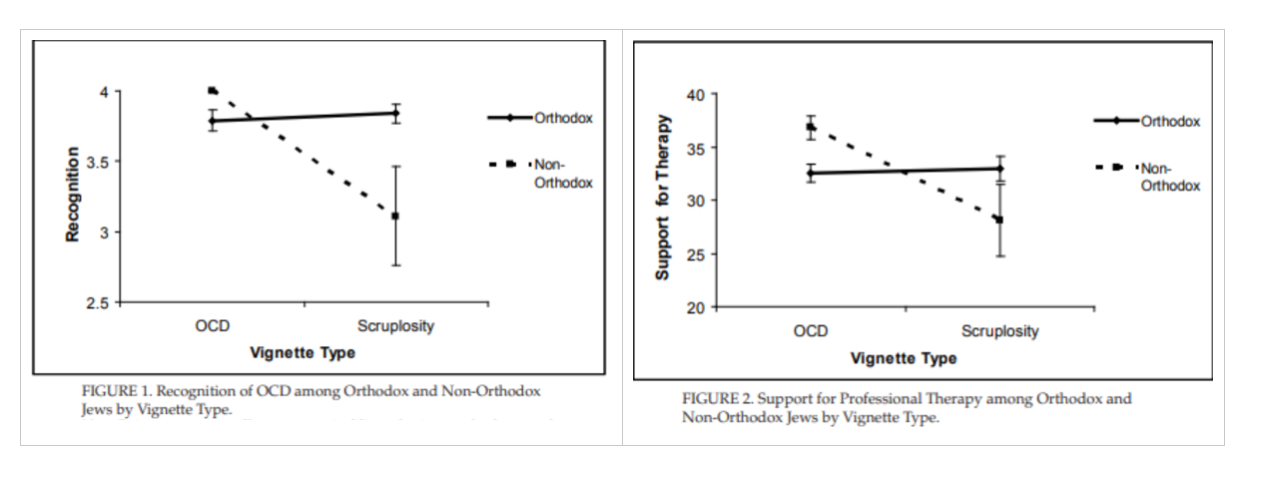

Contrary to expectation, Orthodox Jews were equally likely to recognize both the non-religious and religious vignettes as OCD (82% and 84%), yet non-Orthodox Jews were less likely to recognize the religious vignette as symptomatic of OCD than the non-religious vignette, (44% versus 100%). Figure 1 illustrates this trend, but as you can see there is more variation in the attitudes of the non-Orthodox group than the Orthodox group with regard to the scrupulosity group, suggesting a greater degree of uncertainty.

Orthodox Jews were also equally likely to recommend professional treatment for both scrupulosity and non-religious OCD, whereas non-Orthodox Jews were less likely to recommend professional treatment for scrupulosity compared to non-religious OCD. As with the previous findings, figure 2 also illustrates the greater degree of variation in the non-Orthodox sample's opinions regarding the treatment of scrupulosity.

As Orthodox Jews are more familiar with the expectations for religious observance, they may be more likely to recognize abnormal or excessive behaviour than non-Orthodox Jews. Another possible explanation is that non-Orthodox Jews are more concerned about insulting deeply religious people by labeling their behaviour abnormal. The researchers note the importance of consulting with religious leaders in order to be able to distinguish scrupulosity in a valid and reliable manner, as without a deep understanding of normal cultural and religious practices, errors could easily be made.

Internal validity should have been relatively strong as the researchers analyzed the make-up of the two groups and found no differences in terms of gender, college education, or age. The only difference was in the degree of religiosity as expected according to their self-identification as Orthodox or non-Orthodox.

To assure the validity of the vignettes, researchers asked three Orthodox and three non-Orthodox OCD researchers to check them; all agreed that the two characters both met the criteria for OCD, and each case was equally severe. The researchers also checked with three Orthodox rabbis who agreed that the behaviour described in the scrupulosity vignette was excessive and not in line with Orthodox Jewish standards.

Participants were recruited via the internet and snowball sampling, meaning the findings may not be generalizable to Ultra-Orthodox Jews, some of whom do not use the internet.

Non-Orthodox Jews raised in Orthodox families were deliberately excluded. This means that the findings cannot be generalized to people who have become less rigid in their religious observance over time; this may be an interesting group for consideration.

The sample comprised nearly twice as many females as males meaning making it difficult to draw conclusions about the extent to which male Orthodox Jews are able to differentiate between scrupulosity and OCD; it would be useful to replicate the study with an all-male sample.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team