Bandura (1961)

One of the great classic experiments of social psychology was carried out by Albert Bandura. The study has come to be known as the Bashing Bobo study. The study was investigating whether children could learn aggressive behaviour by watching the behaviour of adults.

One of the great classic experiments of social psychology was carried out by Albert Bandura. The study has come to be known as the Bashing Bobo study. The study was investigating whether children could learn aggressive behaviour by watching the behaviour of adults.

The study is quite complex and has a lot of detail. The summary below gives you more detail than you need for the exam. However, it gives you the full picture of what was done.

The study can be used to discuss social cognitive theory - as well as ethics and research methods in the study of the individual and the group.

Bandura’s approach was an extension of Behaviourism and basically sees people as being shaped by their life experiences. It looks at how we are affected by the rewards and punishments that we experience every day. Bandura's social cognitive learning theory argued that we do not learn only by receiving awards and punishment - but instead, we can learn through observation. When we observe others receive a reward, then we may imitate that behaviour with the goal of getting the same reward. This is known as vicarious reinforcement.

His study is a classic, although you will see that there are some ethical concerns with how the study was carried out.

In this study, Bandura set out to demonstrate that if children are passive witnesses to an aggressive display by an adult, they will imitate this aggressive behaviour when given the opportunity. More specifically, the study made the following predictions:

- children exposed to aggressive models will reproduce aggressive acts resembling those of the models.

- children will imitate the behaviour of a same-sex model to a greater degree than a model of the opposite sex

Thirty-six boys and 36 girls aged between 37 and 69 months were tested. The mean age was 52 months. They used one male adult and one female adult to act as role models.

The study had three major conditions: a control group, a group exposed to an aggressive model and a group exposed to a passive model. The children who were exposed to the adult models were further sub-divided by their gender, and by the gender of the model that they were exposed to. In other words, there were three independent variables. A summary of the groups is shown in the table below.

The eight experimental conditions

| 6 boys with same-sex model - aggressive condition | 6 boys with opposite sex model - aggressive condition | 6 girls with same sex model - aggressive condition | 6 girls with opposite sex model - aggressive condition |

| 6 boys with same-sex model - non-aggressive condition | 6 boys with opposite sex model - non-aggressive condition | 6 girls with same-sex model - non-aggressive condition | 6 girls with opposite sex model - non-aggressive condition |

This is quite a complicated design that appears to cover a lot of different possibilities. However, the number of children in each group is quite small, and the results could be distorted if one group contained a few children who are normally quite aggressive. the researchers tried to reduce this problem by pre-testing the children and assessing their aggressiveness. They observed the children in the nursery and judged their aggressive behaviour on 5-point rating scales. The rating scales assessed the child's level of physical aggression, verbal aggression and aggression towards inanimate objects

A composite score for each child was obtained by adding the results of the ratings. It was then possible to match the children in each group so that they had similar levels of aggression in their everyday behaviour. The observers were the experimenter (female), a nursery school teacher (female) and the model for male aggression. The study reports that the first two observers were “well acquainted with the children”.

A disadvantage of using rating scales in this way is that different observers see different things when they view the same event. This might mean that the ratings will vary from one observer to another. To check the inter-rater reliability of the observations, 51 of the children were rated by two observers working independently and their ratings were compared. The high correlation that was achieved (r = 0.89) showed these observations to be highly reliable, suggesting that the observers were in close agreement about the behaviour of the children.

The children were tested individually. In stage one they were taken to the experimental room which was set out for play. One corner was arranged as the child’s play area, where there was a table and chair, potato prints and stickers, which were all selected as having high interest for the children. The adult model was escorted to the opposite corner where there was a small table, chair, blocks, mallet and Bobo (an inflatable doll). The experimenter then left the room.

In the non-aggressive condition, the model played with the blocks in a quiet manner, ignoring Bobo. In the aggressive condition, the model started to play with the blocks, but after one minute turned to Bobo and was aggressive to the doll in a scripted way. The aggression was both physical (for example, “raised the Bobo doll, picked up the mallet and struck the doll on the head”) and verbal (for example, “Pow!” and “Sock him in the nose!”) After 10 minutes the experimenter returned and took the child to another games room.

In stage two, the child was subjected to “mild aggression arousal.” The child was taken to a room with attractive toys, but after starting to play with them, the child was told that these were the experimenter’s very best toys and she had decided to reserve them for the other children.

Then the child was taken to the next room for stage three of the study. The experimenter stayed in the room “otherwise a number of children would either refuse to remain alone or would leave before termination of the session.” In this room, there was a variety of toys, both non-aggressive (three bears, crayons, and so forth) and aggressive toys (for example, a mallet, dart guns and a three-foot Bobo). The child was kept in this room for 20 minutes and their behaviour was observed by judges through a one-way mirror. Observations were made at five-second intervals giving 240 response units for each child.

The observers recorded three measures of imitation in which they looked for responses from the child that were similar to the display by the adult model:

imitative for physical aggression

imitative for verbal aggression

imitative non-aggressive verbal responses.

In addition, they recorded three types of aggressive behaviour that were not imitation of the adult model: punching Bobo, non-imitative physical and verbal aggression and aggressive gun play.

By looking at the results we can consider which children imitated the models, which models they imitated and whether they showed a general increase in aggressive behaviour rather than a specific imitation of the adult behaviours.

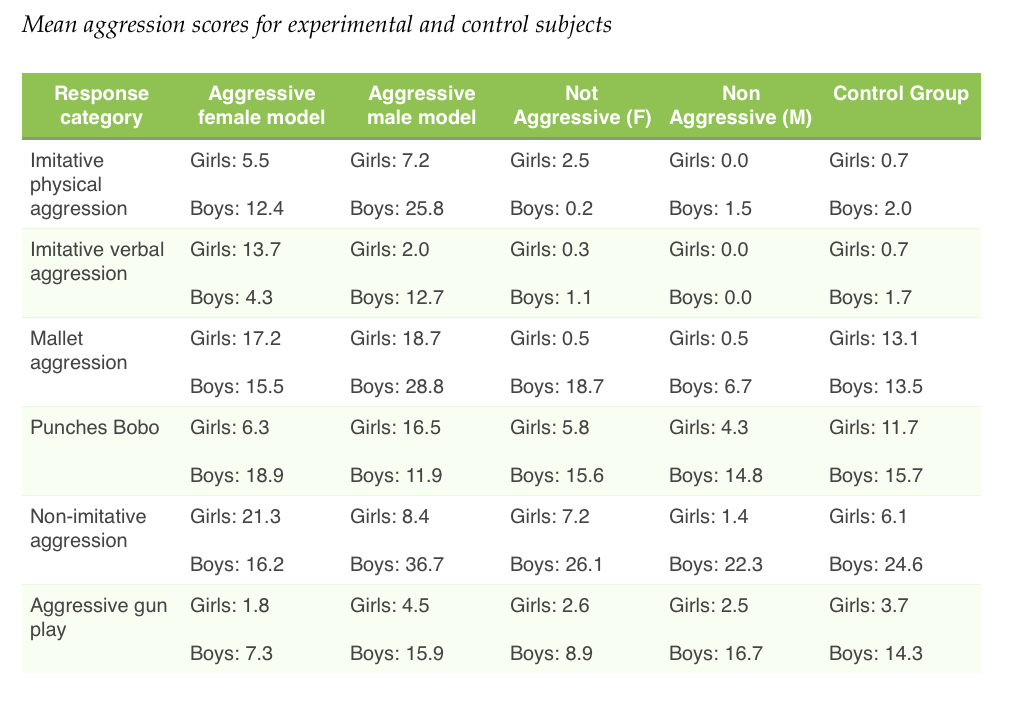

The results are summarised in a chart:

The results above show that:

the children who saw the aggressive model made more aggressive acts than the children who saw the non-aggressive model;

boys made more aggressive acts than girls;

the boys in the aggressive conditions showed more aggression if the model was male than if the model was female;

the girls in the aggressive conditions also showed more physical aggression if the model was male but more verbal aggression if the model was female;

the exception to this general pattern was the observation of how often they punched Bobo, and in this case, the effects of gender were reversed.

The study is an experiment using a matched pairs design. This means that the researchers controlled for the child's level of agression in the different groups.

The sample size was very small. In addition, these were all children of people working at Stanford university. It is difficult to generalize from such a sample.

The study shows that aggression may be learned, but it does not study whether aggression is innate. It is not truly a counter-argument to the theory that aggression has biological origins.

The study is ethically problematic - exposing children to adult violence against the Bobo. The study is cross-sectional, looking only at aggression exhibited as a result of seeing the adult hit the Bobo. It did not monitor long-term effects on the children. It can be argued that the children experienced undue stress and there was a potential for long-term psychological effects on their behaviour.

The situation is highly controlled and it is not normal for children to be left alone with strangers in this way. The study lacks ecological validity.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team