Ebbinghaus (1885)

One of the earliest studies of memory and forgetting was done by Hermann von Ebbinghaus. Although I don't recommend using this study on an examination because it is so old, it is a good example of early psychological research. The study has many methodological concerns.

One of the earliest studies of memory and forgetting was done by Hermann von Ebbinghaus. Although I don't recommend using this study on an examination because it is so old, it is a good example of early psychological research. The study has many methodological concerns.

In addition, this is a good study to know about because so many people like to say, "You know, you only remember 25% of what you learn in school." Understanding this study informs us of where this myth comes from - and actually shows us that the idea that we remember 25% of something is testimony to just how incredible our brains really are!

When we talk about memory, we often neglect to mention the concept of "forgetting." There is a difference between failure to recall a word from a list of words and "forgetting." Forgetting implies that we once knew that word was on the list, but now we can no longer recall that word. Why is it that we forget a memory?

There are basically two theories as to why we forget. The first is that memories decay over time. In other words, if you don't lose it, you lose it. However, there is much debate about whether this theory is really supportable. How many of us can remember the words to a song we have not heard in a very long time? Or the plot of a book we read years ago? Of course, it may have to do with the type of memory that we have created - e.g. episodic vs. declarative - but even then, at the age of 55 I can still remember the formula for photosynthesis and the French poem "Le Corbeau et le Renard." Trust me; I don't need to use these memories very often - if ever!

The other theory is that we forget things because of interference. This means that memories are unable to be retrieved because of interference from similar information acquired before or after their formation. For example, the use of leading questions as seen in the study by Loftus and Palmer.

Ebbinghaus's classic study wanted to control for one of the factors that helps us to remember information - meaning. He wanted to see just how much we would forget over time if the information that we were trying to remember had no inherent meaning. You can see why I think that remembering 25% of something without meaning is a darn good accomplishment of the human brain!

Ebbinghaus carried out a very simple experiment. First, he created a list of three-letter nonsense words, for example: DIF, LAQ, RYC, NED, ....

The goal was to create a list of words with no meaning so that the personal significance of a word would have no influence on the likelihood of recall. In many ways, Ebbinghaus's study foresaw the Levels of Processing Theory.

After creating the list, he then tested himself on the list. Yes, he was the only participant in this study! This is often referred to as an auto-experiment.

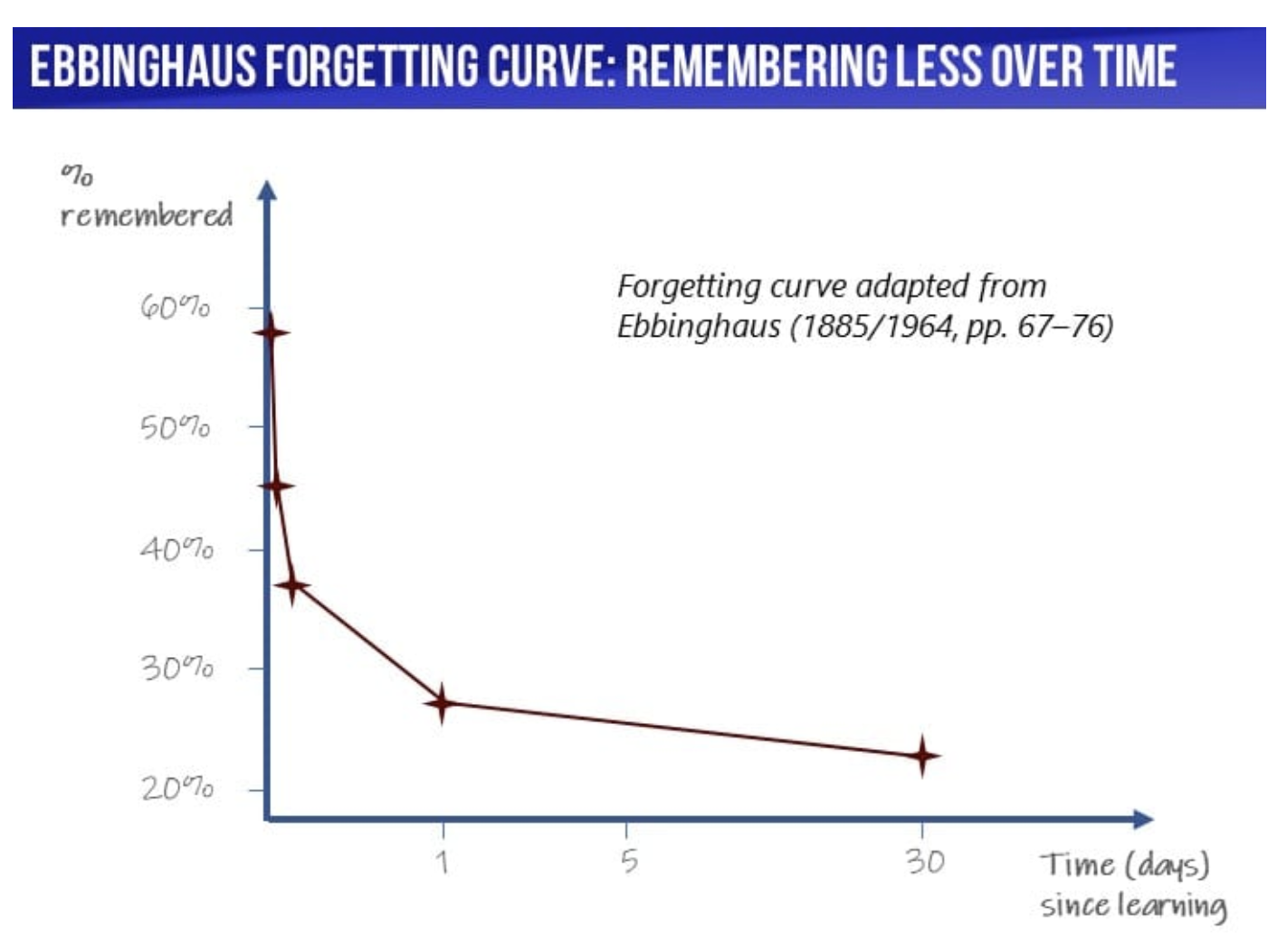

He had two important findings. First, he found that memory decayed over time. In fact, over a very quick period of time! He cound that after only 20 minutes, he could only recall roughly 60% of the list and by the end of the first day he was down to only 28%. Be he also found that his recall leveled off at around 25%.

Secondly, he found that he could improve his recall through spaced repetition. In other words, repeated rehearsal of the list over time. It is important, then, not just to cram for an exam, as this would still see the forgetting curve in action after only 20 minutes! Instead, more frequent revision over time results in a stronger recall of information.

The fact that Ebbinghaus designed and carried out the study on himself makes this study highly problematic. However, the study has been replicated and the results have been shown to be reliable.

The study has controlled for the meaning of the words, removing an important variable that often confounds studies of memory.

Although the control for meaning may increase the internal validity of this study, it definitely lowers the ecological validity of the study. How often do we have to learn completely meaningless material in school?

The study seems to support the idea of memory decay that will be an important part of the Multi Store Model. However, attempts to study the long-term decay of memories is problematic as there are so many other variables that could account for forgetting. In addition, although we know that neural pruning takes place, there is very limited evidence that this is responsible for the loss of specific memories.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team