Culture and cognition

Culture has many effects on our behaviour, our attitudes, and our cognitive processes. Culture plays a role in the creation of our schema - and these, in turn, affect what we remember. However, it also affects how we remember. The following chapter explores how culture affects the cognitive process of memory.

Culture has many effects on our behaviour, our attitudes, and our cognitive processes. Culture plays a role in the creation of our schema - and these, in turn, affect what we remember. However, it also affects how we remember. The following chapter explores how culture affects the cognitive process of memory.

Research in psychology: Cole and Scribner (1974)

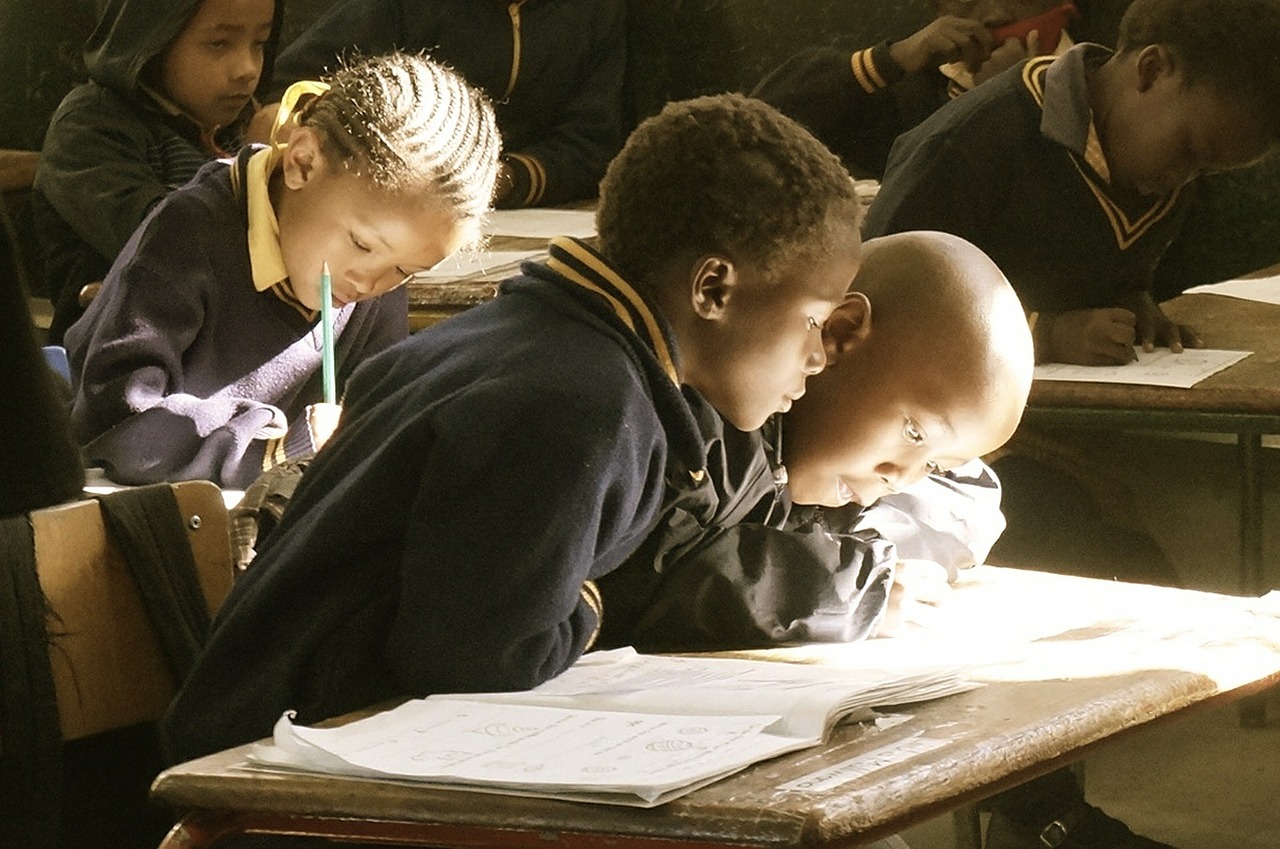

Cole & Scribner used an emic approach to see how culture could affect memory. They wanted to see the effect that schooling would have on the strategies that children used to memorize lists of words.

Cole & Scribner (1974) studied the development of memory among tribal people in rural Liberia compared to children in the US. They looked at both Liberian children in school and those that were not attending school. To overcome the barriers of language and culture, these researchers observed everyday cognitive activities before conducting their experiments and worked closely with the university-educated local people who acted as experimenters.

The aim of the study was to see if culture had a different effect on how one memorizes. They were given a free-recall task people, in which they were shown a large number of objects, one at a time, and then asked to remember them. This kind of memory is called “free” recall because people are free to recall the items in any order they wish.

Below is a list of the 20 objects used in several of Cole and Scribner’s studies. The list shows that the objects appear to fall into four distinct categories. To make sure that the list was not too ethnocentric - and thus, foreign to the Liberian participants - the researchers ran a pilot study to make sure that Liberian participants were familiar with the words.

| The word list used in research by Cole and his colleagues | |

Plate Calabash Pot Pan Cup | Cutlass Hoe Knife File Hammer |

Potato Onion Banana Orange Coconut | Trousers Singlet Head tie Shirt Hat |

The researchers found that unlike the children in school, the children who were not attending school showed no regular increase in memory performance after the age of 9 or 10. These participants remembered approximately ten items on the first trial and managed to recall only two more items after 15 practice trials. The Liberian children who were attending school, by contrast, learned the materials rapidly, much the way schoolchildren of the same age did in the United States.

School-children in Liberia and the United States not only learned the list rapidly but used the categorical similarities of items in the list to aid their recall. After the first trial, they clustered their responses; for example, they would recall items of clothing, then items of food, and so on. The non-schooled Liberian participants did very little clustering, indicating that they were not using the categorical structure of the list to help them remember.

In a later trial, the researchers varied the recall task so that the objects were now presented in a meaningful way as part of a story. The unschooled children recalled the objects easily and actually chunked them according to the roles they played in the story.

Memory studies like these invite reflection. It seems that even although the ability to remember is universal, strategies for remembering are not universal. Generally, schooling presents children with a number of specialized information-processing tasks, such as organizing large amounts of information in memory and learning to use logic and abstract symbols in problem-solving. It is questionable whether such ways of remembering have parallels in traditional societies like the Kpelle children studied by Cole and Scribner. The conclusion is that people learn to remember in ways that are relevant for their everyday lives, and these do not always mirror the activities that cognitive psychologists use to investigate mental processes.

A quasi-experiment carried out by Kearins (1981) investigated why Aboriginal children tend to score low on Western verbal intelligence tests. As a traditional society, Aboriginal people used to spend most of their lives in the desert. Their survival depended to a large extent on their ability to store or encode enormous amounts of environmental or visual information. Kearins wanted to see how the Aboriginal people's spatial memory compared to those of non-Aboriginal Australian children.

Kearins (1981) had a sample of forty-four adolescents aged 12 - 16 years (27 boys, 17 girls) of desert Aboriginal origin and 44 adolescents (28 boys, 16 girls) of white Australian origin. Kearins placed 20 objects on a board divided into 20 squares. Aboriginal and white Australian children were told to study the board for 30 seconds. Then the objects were gathered together and placed in a pile in the center of the board and the children were asked to place the objects on the board in the same arrangement. The results showed that the Aboriginal correctly relocated more objects than did white Australian children. It appears that their way of life has a significant impact on how and what they remember. Cole & Scriber's study showed, children learned memory strategies through their formal education - but education is not only "in school" but by the way that we are raised by our parents. Kearins argues that the first generation settled parents raised their children in a way that reflects the traditional lifestyle and values - and this, in turn, affects the way that they learn.

Here you can read a more detailed description of Kearins (1981) study.

ATL: Thinking critically

1. Why is this study considered a "quasi-experiment?" What are the limitations of this method?

2. If the children were not raised in the desert, how do you think that the parents may have taught them this skill?

3. Do you think that you could develop the same skills that the Aboriginal children showed in this study? How would you go about learning this skill?

1. Why is this study considered a "quasi-experiment?" What are the limitations of this method?

The children could not be randomly allocated to conditions. They were separated based on their cultural heritage. The limitation of the method is that a cause-and-effect relationship cannot be determined.

2. If the children were not raised in the desert, how do you think that the parents may have taught them this skill?

It is most likely that this skill was learned indirectly - through observational learning. However, it could also have been learned through participatory learning - that is, play activities between parent and child where feedback was given to the child to help them improve their skills.

3. Do you think that you could develop the same skills that the Aboriginal children showed in this study? How would you go about learning this skill?

Some students will argue that they could not learn this skill. The question is why they would not be able to. Answers will vary.

A final example of the role of culture in cognition is a study by Kulkofsky et al (2011). The researchers studied five countries - China, Germany, Turkey, the UK, and the USA - to see if there was any difference in the rate of flashbulb memories in collectivistic and individualistic cultures. There were 274 adults from the five different countries.

Participants were given five minutes to recall as many memories as they could of public events in their lifetime. They were then given a memory question which was similar to the one used by Brown & Kulik (1977). These questions included where they had learned of the event, what time of day it was and what they were doing when they heard about it. They were then asked questions about the importance of the event - including how personally important it was, how surprised they were and how often they had spoken about it since it happened. All questionnaires were provided in the native language of the participants.

The researchers found that in a collectivistic culture like China, personal importance and intensity of emotion played less of a role in predicting flashbulb memories, compared with more individualistic cultures that place greater emphasis on an individual's personal involvement and emotional experiences. Because focusing on the individual's own experiences is often de-emphasized in the Chinese context, there would be less rehearsal of the triggering event compared with participants from other cultures - and thus a lower chance of developing a flashbulb memory. However, it was found that if the event was of national importance, then there was no significant difference in the creation of flashbulb memories.

You can read more about Kulkofsky et al (2011) here.

Checking for understanding

Why could we consider Cole & Scribner’s study an emic approach?

An emic approach takes culture into consider when designing materials for a study.

What were Cole & Scribner’s findings regarding cognition?

The study is cross-sectional - that is, there was no study of the children "over time." The study examined the role of schooling in teaching students "chunking strategies." Children who did not go to school did not automatically learn the list of words by chunking (or categorizing) them in lists. This appears to be a skill that is learned.

Why is Kearins’ study of memory in Aborigines considered a quasi-experiment?

The participants were allocated to groups based on whether they were Aboriges or Australians - and their performance on the task was compared. A true experiment would be able to randomly allocate participants to either condition. There is an independent variable - culture - but this cannot be manipulated by the research. Hence the term "quasi-experiment."

How does Hofstede’s theory of individualistic vs collectivistic cultures explain Kulkofsky’s findings with regard to flashbulb memory?

When thinking about world events, it is normal in individualistic societies to focus on yourself - whereas in collectivistic cultures the focus would be more on the community or country.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team