Crum (2011)

Biological research has shown that hormones play a key role in our feelings of hunger and satiety. Health psychologists argue that when the feedback loops that lead to hunger and satiety are somehow disrupted, this may lead to obesity or other disordered eating patterns. Biologists discuss these disruptions as a fault of some biological mechanism.

Biological research has shown that hormones play a key role in our feelings of hunger and satiety. Health psychologists argue that when the feedback loops that lead to hunger and satiety are somehow disrupted, this may lead to obesity or other disordered eating patterns. Biologists discuss these disruptions as a fault of some biological mechanism.

Crum et al (2011), however, argue that cognition may be a mediating factor. This study may be used to discuss a cognitive explanation of obesity, as well as research methods and ethical considerations in health psychology.

A video of the experiment is included below.

Ghrelin is a hormone secreted in the gut that travels to the brain through the bloodstream and binds to receptor sites on the hypothalamus. Ghrelin works on a positive feedback loop - that is, when our energy levels are low, ghrelin is secreted as a way to let us know that we have to eat something. Ghrelin produces a feeling of hunger. As we begin eating and our energy levels rise, the level of ghrelin falls, leaving us feeling satisfied or satiated. One of the biological theories of obesity is based on the failure of this positive feedback mechanism.

Research has shown that our cognition affects the way our brain interacts with food. For example, Plassmann et al (2008) found that manipulating the cost of wine to be more expensive can result in heightened activity in the pleasure centers of the brain. Cognitive psychologists also argue that the way we think about food may act as a mediating factor on ghrelin levels.

Crum et al (2011) carried out a study to see if one's perception of the number of calories in a milkshake would affect their body's response and their subjective feeling of satiety (fullness).

The sample was made up of 46 participants who were recruited by posting fliers in the local community. The participants were asked to take part in a "shake tasting study." The participants were between 18 and 35-years-old and were all within a normal range of body mass – that is, there were no obese participants. 78% of the sample was made up of university students.

The participants were asked to attend two tasting sessions that were one week apart. In this repeated measures design, in one visit they drank the "indulgent shake" - which they were told had 620 calories; in the second session, they were given the "sensible shake" with only 140 calories. However, they were actually the same shake, with 380 calories. The only difference was how many calories the participants believed were in the shake. Prior to the experiment, they were asked to not eat any breakfast before showing up for their 8 am meeting with the researchers.

The study was counterbalanced so that some drank the indulgent shake the first week and some drank the sensible shake the first week. The participants also had three tests to measure their ghrelin levels - one at the beginning to measure the baseline level of ghrelin, one just before consuming the shake (the anticipation condition) and one after consuming the shake. They were also asked how they liked the shake, how attractive it looked, how enjoyable it was and whether they thought it was a healthy choice. This was done to make sure that they had the appropriate mindset. Finally, they were asked whether they felt "full" after drinking it.

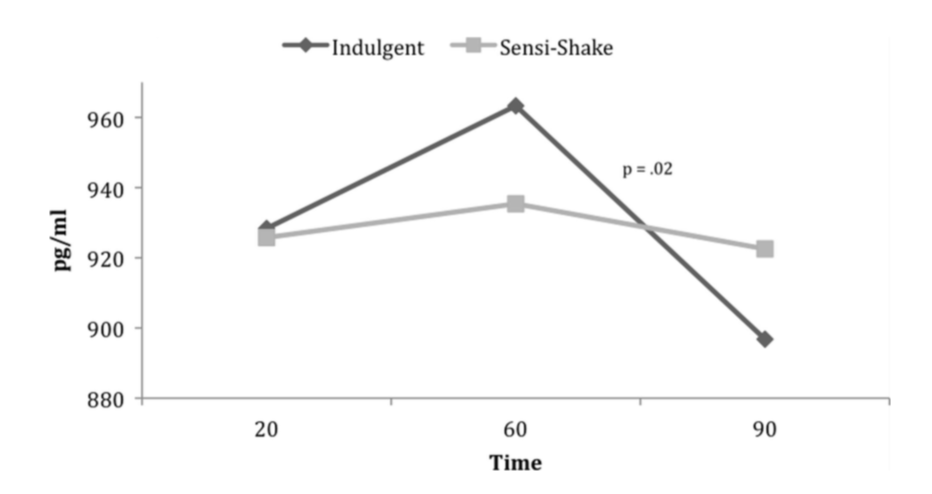

The following graph shows the levels of ghrelin over time.

There was no significant difference between the groups for anticipation – it was all due to consumption.

There was no significant difference between the groups for anticipation – it was all due to consumption.

When the participants thought that they were drinking the indulgent shake, they had a steep decline in ghrelin after consumption, whereas when they drank the "sensible shake," ghrelin levels remained relatively flat. The participants' reporting on satiety was consistent with what they believed they were consuming, rather than the nutritional value of what they consumed.

The study is experimental. The independent variable is manipulated and the dependent variable is measured, allowing the researchers to establish a cause and effect relationship.

The study used deception. This is an ethical concern but was done to avoid expectancy effects.

The study was counterbalanced. This was done to make sure that simply having one shake before the other did not have an effect on the results.

The study has interesting implications for healthy eaters. For example, a breakfast cereal might be a good source of fiber but still have a high level of sugar. Believing that the cereal is healthy may mean that the feeling of satiety does not happen as quickly as if we focused on the sugar content, leading us to consume more of the cereal. This combination of good news with poor nutritional value may be dangerous.

The sample size is relatively small. The study would need to be replicated to establish the reliability of the data.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team