Thinking and decision making

We are constantly bombarded by information. As we have already learned, to cope with so much information, we often choose not to process it by not paying attention to it. However, when we pay attention to the stimuli around us, we engage in a process known as thinking. Thinking is the process of using knowledge and information to make plans, interpret the world, and make predictions about the world in general.

There are several components of thinking - these include problem-solving, creativity, reasoning, and decision-making. For this chapter, we will focus on decision making which is defined as the process of identifying and choosing alternatives based on the values and preferences of the decision-maker. Decision-making is needed during problem-solving to reach the conclusion. Problem-solving is thinking that is directed toward solving specific problems by means of a set of mental strategies. The concepts of problem-solving, decision-making, and thinking are very much interconnected. For the IB when discussing either decision-making or problem-solving, you are also addressing the goals of understanding "thinking and decision-making."

The Dual Process Model of Thinking and Decision Making

The face here on your left demonstrates a clear emotion. Which one is it? When you look at the photo, you do not have to do a lot of thinking about how this person feels - she is clearly disgusted.

However, what if I were to ask you the following question:

A mountain goat attempts to scale a cliff sixty feet high. Every minute, the goat bounds upward three feet but slips back two. How long does it take for the goat to reach the top?

This question is not as easy as the first. If you have done problems just like this before, you may have a quick answer, but for most people, it will take a little bit of time to work out the answer - which is fifty-eight minutes. Although his net progress each minute is one foot, he reaches the top on the fifty-eighth minute just before he would normally slip back two feet.

The two questions above show that different kinds of problems require different ways of thinking. The Dual Process Model of thinking and decision-making postulates that there are two basic modes of thinking - what Stanovich and West (2000) refer to as "System 1" and "System 2."

System 1 is an automatic, intuitive, and effortless way of thinking. System 1 thinking often employs heuristics - that is, a ‘rule’ used to make decisions or form judgments. Heuristics are mental shortcuts that involve focusing on one aspect of a complex problem and ignoring others (Lewis, 2008). This ‘fast’ mode of thinking allows for efficient processing of the often complex world around us but may be prone to errors when our assumptions do not match the reality of a specific situation. These errors may have greater consequences in our day-to-day lives because system 1 thinking is expected to create a greater feeling of certitude – certainty that our initial response is correct.

Gilbert and Gill (2000) have argued that we become more likely to use System 1 thinking when our cognitive load is high - that is, when we have lots of different things to think about at the same time, or we have to process information and make a decision quickly.

System 2 is a slower, conscious, and rational mode of thinking. This mode of thinking is assumed to require more effort. System 2 starts by thinking carefully about all of the possible ways we could interpret a situation and gradually eliminates possibilities based on sensory evidence until we arrive at a solution. Rational thinking allows us to analyze the world around us and think carefully about what is happening, why it is happening, what is most likely to happen next, and how we might influence the situation. This mode of thinking is less likely to create feelings of certitude and confidence.

Characteristics of System 1 and System 2 thinking

| System 1 | System 2 |

| Context-dependent - focuses on existing evidence and ignores absent evidence | Abstract |

| Concerns everyday decision making | Conscious reasoning |

| Generates impressions and inclinations. | Logical and reliable |

| Not logic-based and prone to error | Slow and requiring effort |

| Operates automatically and quickly with little or no effort | Transfers information from one situation to a new situation. |

It is important to remember that we often use both of these systems when addressing a problem. System 1 will reach a quick conclusion and then System 2 will go into further analysis to hopefully reach a "more correct" conclusion. Because System 1 is activated before System 2 can do its work, often System 1 interferes with the effectiveness of System 2.

Research in psychology: Wason 1968

One example of research that supports the dual-process model is based on the Wason selection task.

One example of research that supports the dual-process model is based on the Wason selection task.

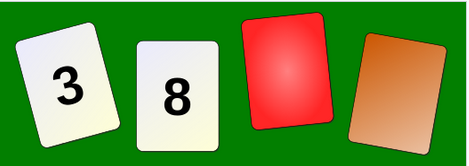

The image to the left is an example of the task. Participants would be shown this set of cards and asked the following question: Which card(s) must be turned over to test the idea that if a card shows an even number on one face, then its opposite face is red?

If you are like most people you will choose the cards with the number "8" and the "red" card. But this is incorrect. We make this decision based on what Wason called matching bias - that is, in an abstract problem, we tend to be overly influenced by the wording (or context) of the question. In this case, the words "even number" and "red."

First, if you guessed "8" and "red", here is an explanation of why that answer is not correct.

- If the 3 card is red, that doesn't violate the rule. The rule makes no claims about odd numbers.

- If the 8 card is not red, it violates the rule. So, this card is the correct choice.

- If the red card is odd, that doesn't violate the rule. The rule is not "if the card is red on one face, then its opposite side is an even number."

- If the brown card is even, it violates the rule.

Evans and Wason (1976) found that when asked why they chose the cards that they did, they were not able to clearly explain their choices.

The Wason selection task provides important evidence for the dual-process model. Most people make the decision of which cards to choose without any reasoning - but as an automatic response to the context of the question. Wason (1968) found that even when he trained people how to answer this question, when he changed the context, the same mistakes were made. For example, can you solve this one?

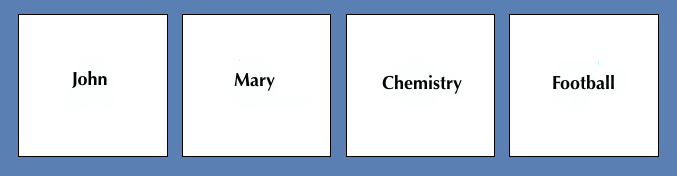

Which cards would you have to turn over in order to prove if the following statement is true? If there is a male's name on one side of the card, then there is an IB subject on the other side of the card.

Many people would choose John and Chemistry. But you would need to turn over John and Football.

If you got this wrong, this shows how powerful System 1 can be. It can interfere with System 2, even when you have learned the "right way to do things."

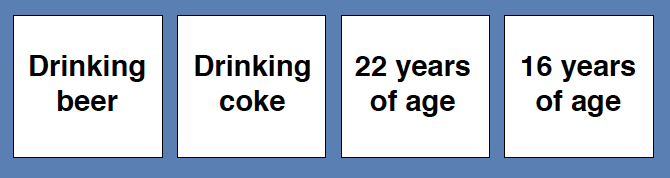

Griggs and Cox (1982) found that when the task is not abstract, we do not tend to show a matching bias. Try to solve this final logic puzzle.

Which cards would you have to turn over in order to prove if the following statement is true? If a person is drinking beer, then that person must be over 18 years old.

If you chose "drinking beer" and "16 years of age," then you are correct. Researchers have found that when the task is not abstract, 75% of people are able to correctly answer the question. When the task is not abstract, System 1 works just fine in solving the problem.

Biological evidence supports what we see in the Wason Selection Task by showing that different types of processing may be located in different parts of the brain. Goel et al (2000) had participants carry out a logic task similar to the ones above. In some cases, the task was abstract in nature (for example, an odd number and a matching colour). In contrast, some of the tasks were "concrete" in nature (for example, drinking beer and under 18). The researchers had the participants decide on the correct choices while in an fMRI. Although there were many common areas of the brain that were active in solving the problems, there was a clear difference. When the task was abstract, the parietal lobe was active; when the task was concrete, the left hemisphere temporal lobe was active. The parietal lobe is often associated with spatial processing. This seems to indicate that the brain processes these two types of information differently - and thus may be seen as support for the model.

ATL: Inquiry

One of the ways that researchers study how people make decisions is to have them think aloud. This is a special type of interview often called a verbal protocol. Theoretically, this is an important way for researchers to "see" what people are thinking.

One of the ways that researchers study how people make decisions is to have them think aloud. This is a special type of interview often called a verbal protocol. Theoretically, this is an important way for researchers to "see" what people are thinking.

But how easy do you think it is for people to explain what they are thinking?

To find out, carry out the following verbal protocol on a friend or family member.

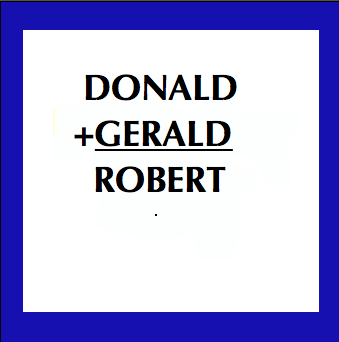

Give the participant a piece of paper with the following problem written on it in the following format.

In addition, give them the following instructions. Please find the numerical value of each letter in this problem. Each letter is assigned a value from zero to nine. None of the numbers 0 - 9 may be used for more than one letter. To get you started, D = 5.

In addition, give them the following instructions. Please find the numerical value of each letter in this problem. Each letter is assigned a value from zero to nine. None of the numbers 0 - 9 may be used for more than one letter. To get you started, D = 5.

Please solve the problem "out loud." Explain your strategy to me so that I can understand how you are solving this puzzle.

After having completed the puzzle, consider the following questions.

1. How easy was it for your participant to think aloud while solving the problem? Why do you think that this is true?

2. Do you think that training people to "think aloud" would be helpful to researchers? Why or why not?

Strengths

There is biological evidence that different types of thinking may be processed in different parts of the brain.

The Wason selection task and other tests for cognitive biases (see the next part of this chapter) are reliable in their results.

Limitations

The model can seem to be overly reductionist as it does not clearly explain how (or even if) these modes of thinking interact or how our thinking and decision-making could be influenced by emotion.

The definitions of System 1 and System 2 are not always clear. For example, fast processing indicates the use of System 1 rather than System 2 processes. However, just because processing is fast does not mean it is done by System 1. Experience can influence System 2 processing to go faster.

Checking for understanding

Which of the following statements is true about thinking, decision making and problem solving?

Mary believes that she is an excellent math student. In fact, her favourite unit is statistics. However, when she is asked to critically evaluate the data of an experiment in psychology class, she does not know how to do it. How does the Dual Process model explain this?

System 1 thinking does not transfer well to new situations. It is possible that Mary is doing well in mathematics, but she may not really understand the maths that she is studying. Instead, she has developed strategies for solving problems in a way that produces low effort cognitive processing - that is, System 1 thinking.

If I meet two students from your school and they are brilliant psychology students, I may then conclude that your school must have an amazing psychology program. This conclusion follows a simple “rule of thumb” or a mental short-cut called a

When are we more likely to use System 1 thinking?

Which of the following is not a characteristic of System 1 thinking?

Which of the following statements is true about the Wason selection task?

Which of the following is not a characteristic of System 2 thinking?

According to Goel et al (2000), which part of the brain may be responsible for processing abstract problems?

Which of the following is not a limitation of the Dual Process Model?

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team