Cognitive approach to anxiety

The cognitive approach to explaining anxiety disorders focuses on how people process information. Individuals with anxiety disorders tend to focus on threat-relevant information in their environment. For example, when speaking in a group, a socially anxious individual is likely to notice threatening facial expressions (e.g., anger) rather than neutral expressions. They may also be more likely to interpret a negative facial expression as indicative of a person’s disgust with the speaker rather than the content of the conversation. This misinterpretation of the situation - a form of cognitive bias - is believed to be the root of anxiety disorders.

The cognitive approach to explaining anxiety disorders focuses on how people process information. Individuals with anxiety disorders tend to focus on threat-relevant information in their environment. For example, when speaking in a group, a socially anxious individual is likely to notice threatening facial expressions (e.g., anger) rather than neutral expressions. They may also be more likely to interpret a negative facial expression as indicative of a person’s disgust with the speaker rather than the content of the conversation. This misinterpretation of the situation - a form of cognitive bias - is believed to be the root of anxiety disorders.

Cognitive biases

Clark (1986) used the term catastrophizing to explain the thinking patterns of people with panic disorder. Catastrophizing is a cognitive distortion where a person exhibits an exaggerated sense of negativity, assuming the worst outcomes and interpreting even minor problems as major calamities. Catastrophising also results in a belief that one's own personal risk is higher than that of others.

Butler and Mathews (1983) hypothesized that anxious individuals overestimate subjective personal risk. They presented negative (or unpleasant) and positive (or pleasant) statements of events to highly anxious individuals and control participants. All participants were asked to subjectively rate the statements on a 0–8 scale of future probability, where 0 = “not at all likely” and 8 = “extremely likely.” Anxious individuals significantly overestimated subjective personal risk for negative events when compared with controls, especially if those events were self-referent

Another way to show that people with anxiety disorders are focused on personal risk to perceived threats is by measuring the level of interference in the Stroop test, in which individuals are shown threat-related words and control words printed in different ink colors. Individuals are asked to name the ink color of the word. Significant delays in color naming are thought to measure a high level of attention to the word stimuli. Research has shown a substantial delay in naming colors of threat-related words in samples of people with general anxiety disorder (Taghavi et al, 2003).

Inquiry: Can a computer game cure anxiety?

One of the ways that we can support a theory of the origins of a disorder is to see if therapies based on those theories actually make a difference. Watch the following video on Cognitive Bias Modification therapy.

What do you think about the speaker's argument? Dig a bit deeper into this therapy. You can find the app he is talking about at this site. Do you think that this is just a way to get people to buy an app - or do you think that there is some legitimacy to the claims in the video?

Be able to discuss how you would use this app to test the theory that cognitive biases are the cause of anxiety disorders.

What do you think about the speaker's argument? Dig a bit deeper into this therapy. You can find the app he is talking about at this site. Do you think that this is just a way to get people to buy an app - or do you think that there is some legitimacy to the claims in the video?

Have students look for studies of the effectiveness of cognitive bias modification apps. You may want to give them the links below (see the next textbox).

There is some legitimacy to the research, but the research overall on this method is mixed.

Be able to discuss how you would use this app to test the theory that cognitive biases are the cause of anxiety disorders.

One of the problems of testing the effectiveness of an app like this is that there are so many variables that may affect one's level of anxiety. Carrying out a field study with the app means a lack of internal validity, which means that a cause and effect relationship is difficult to determine. It means that a positive effect may not be attributed solely to the use of the app; a lack of a positive effect also may not be attributed to the app.

Cognitive bias modification resources

Amir, N., Weber, G., Beard, C., Bomyea, J., & Taylor, C. T. (2008). “The effects of a single-session attention modification program on response to a public-speaking challenge in socially anxious individuals.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 860-868.

Michael Browning, Emily A. Holmes, Susannah E. Murphy, Guy M. Goodwin, and Catherine J. Harmer (May 15, 2010) “Lateral Prefrontal Cortex Mediates the Cognitive Modification of Attentional Bias” Biol Psychiatry. 67(10): 919–925.

Amir, N., Beard, C., Burns, M., and Bomyea, J. “Attention modification program in individuals with generalized anxiety disorder”. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009; 118: 28–33

The role of control

In addition to cognitive biases, one's sense of control over their situation - and especially with regard to being able to control their own fears - plays a critical role in anxiety disorders.

Key study: Telch and Harrington (2011)

Telch and Harrington (2011) wanted to see the role that one's sense of control would play in panic attacks.

Telch and Harrington (2011) wanted to see the role that one's sense of control would play in panic attacks.

For the study, they used a sample of 79 introductory psychology students, 45 men and 34 women between the ages of 18 and 29, who participated for partial class credit at the University of Texas at Austin. None of the participants had a history of panic attacks.

The participants were labeled as "high" or "low" risk for panic attacks based on their scores on the Anxiety Sensitivity test. The test measures their self-reported anxiety as a response to physical symptoms - eg. heart beating rapidly or feeling faint.

The study was a 2 x 2 factorial design. That means that there were two independent variables manipulated by the researchers. First, participants for both the high and the low anxiety groups were randomly allocated to either the "relaxation" group or the "arousal" group. In each of those groups, participants would be asked to breathe in a gas. In one case, they breathed room air and in the other, they breathed air with a 35% concentration of carbon dioxide. Each group was exposed to both gasses. The experiment was counter-balanced.

In the relaxation condition, they were read the same instructions as in the other condition, except they were told that they may experience various physical feelings of relaxation, such as lightheadedness, a slight tingling in the extremities, or a sense of floating or being detached from your body.

The arousal condition was told that they may experience rapid breathing, heart rate acceleration, sweating, and dizziness or lightheadedness.

They were told to breathe in and then hold their breath for five seconds while the experimenter counted - and then exhale. They were then asked to fill in two forms - the API and SUDS.

The API is a 17-item inventory for assessing symptoms associated with panic attacks. Examples include, “Do you feel faint?”, “Are you afraid of dying?”, “Do you feel detached from part or all of your body?”, and “Do you have palpitations?”

The SUDS is a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not disturbed at all) to 100 (the worst imaginable experience) used to measure self-reported fear, anxiety, and breathlessness.

In addition, during the experiment, the participants' heart rate was monitored through the use of a wrist monitor microcomputer.

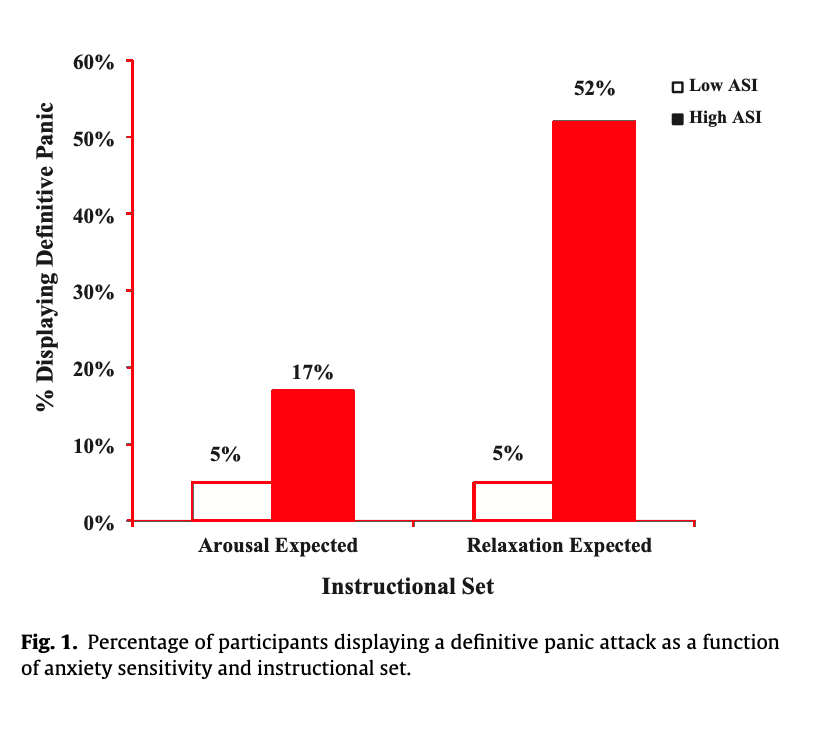

Figure 1 Percentage of panic attacks (Telch and Harrington, 2011)

You can see in the graph on the left that when arousal was expected - that is, the individuals could prepare for the feelings of arousal from the carbon dioxide, in both the low and the high anxiety participants the frequency of panic symptoms was relatively low. However, in the case where they were expecting to relax and were then experiencing unexpected symptoms, those with high levels of anxiety started to panic. It was the lack of control over their situation which is believed to have led to their panic response.

Another study on the role of perceived control was carried out by Sanderson, Rapee, and Barlow (1989). In this study, patients with actual panic disorder were the participants. The participants were asked to breathe in carbon dioxide. They were also told that a light went on and they could turn a dial to regulate the level of carbon dioxide. However, this was not true. The dial had no function at all.

The participants were randomly allocated to one of two conditions. In the "high control" condition, the light went on as soon as they started to breathe in. In this case, they had the perception that had the ability to regulate the flow of carbon dioxide. In the "low control" condition, the light never came on. 80% of the low control group had a panic attack, whereas only 20% of the high control group did. As all of the participants in this study breathed in carbon dioxide and experienced arousal as a result, we can see that is the cognitive aspect of control which played a greater role in their panic attacks rather than physiological factors.

Strengths

- Experimental research has been used to support the role of cognitive factors in anxiety disorders.

- Practical application of the theories has led to successful treatments that have improved some people’s lives.

Limitations

- For ethical reasons, people with actual anxiety disorders are often not used in research. As a result, "anxiety" or "panic symptoms" are measured, rather than actually diagnosed anxiety disorders.

- Correlational research means that causation cannot be established and bidirectional ambiguity cannot be resolved. It is unclear whether the thinking patterns are the cause or the result of anxiety disorders.

- The Treatment Aetiology Fallacy – that is, the mistaken notion that the success of a treatment reveals the cause of the disorder.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team