Eugene Pauly (Squire, 1992, 2002)

The case study of HM is only one case study that can teach us about the nature of memory. Another study that changed the way that we understand the way that memories are developed is the case study of Eugene Pauly [EP]. The research was carried out by Squire and his team at MIT.

The case study of HM is only one case study that can teach us about the nature of memory. Another study that changed the way that we understand the way that memories are developed is the case study of Eugene Pauly [EP]. The research was carried out by Squire and his team at MIT.

The case study of EP can be used to address the following content in the biological approach:

Localization of function

Research methods & techniques to study the brain and behaviour.

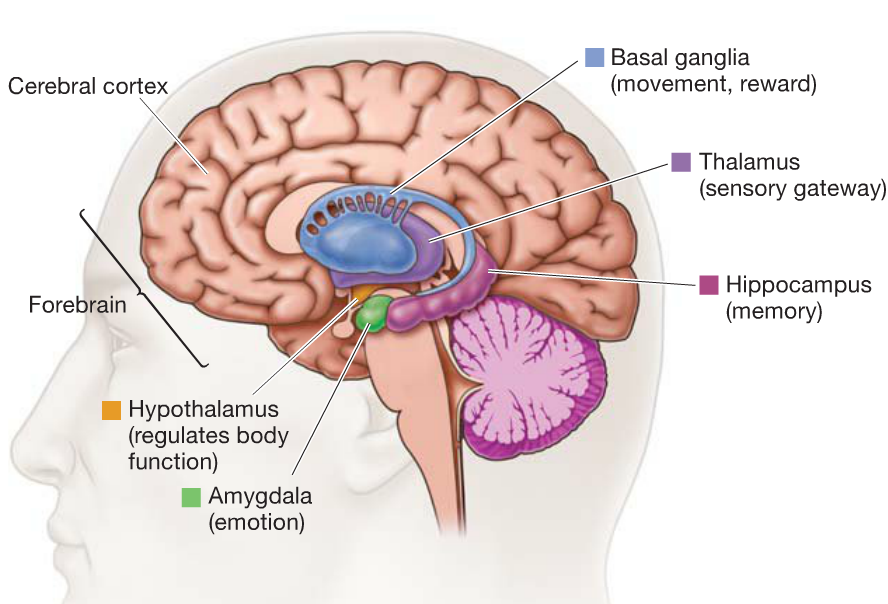

In 1992 Larry Squire and his team were introduced to one of the most interesting cases of amnesia since the famous HM study. At the age of 70, Eugene Pauly was diagnosed with viral encephalitis. His physical recovery was amazing, but his cognitive impairment was very significant. He had large lesions on his medial temporal lobe, the part of the brain responsible for the formation of long-term memory. Both the amygdala and the hippocampus were completely destroyed.

When he returned home with his wife, the results of this cognitive impairment began to show. He couldn't remember the day of the week, the names of nurses or doctors or friends. He had trouble following a conversation but could talk about topics that interested him. Often he would repeat the same story or comment several times in a single afternoon. He would often forget what he had already done and as a result, he would eat breakfast several times in a single day.

Although he could not form new declarative memories, he could recall and discuss most of the events of his life that happened prior to 1960. - three decades earlier.

Unlike HM, he was still socially functional. Whenever someone walked in the room, he would introduce himself and ask them about their day.

Squire carried out a series of interviews with EP at his home. During one interview he asked EP to draw a map of his home. He was not able to do it. However, EP excused himself and got up to go to the toilet. How could a man that could not draw a map of his home find the bathroom on his own? When sitting in the living room, he could not identify which door led to the kitchen. But if Squire asked him to get him something to eat, he immediately got up and headed for the kitchen.

This was a behaviour not seen in HM. It led Squire and his team to carry out a case study that would deepen our understanding of how memory works.

A case study triangulates in order to establish the credibility of the findings. In this case study, Squire & his team carried out several different methods:

- Interviews with EP and his family; for example, EP was unable to describe how he would travel from his home to locations in his neighbourhood that he visits with his wife

- Psychometric testing: for example, IQ testing - which proved no impairment of intelligence.

- Observational studies - watching how EP solved problems or behaved on memory tasks. For example, EP could not remember a string of numbers

- MRI: found that the anterior temporal lobe was the most damaged - including the amygdala and hippocampus.

One of the important tests done was the Autobiographical Memory Interview. The AMI is a structured interview that asks for detailed information about three periods of life: childhood, early adult life, and recent life. Within each of these periods EP’s memory was tested for both personal semantic knowledge (e.g., What was your home address while attending high school?) and autobiographical memory (e.g., Describe an incident that occurred while you were attending elementary school). The accuracy of all his responses was verified by at least two family members. For the recent time period, EP performed extremely poorly. He did better at answering questions about his early adult life, but his scores were still below the control scores. In contrast, EP performed normally when answering questions about his childhood, scoring nearly as high as the highest-scoring control subjects.

Another important finding was an experiment in which Squire took 16 different objects and glued them on cardboard rectangles. He then organized the objects in 8 pairs. On the bottom of one of the objects in each pair was written the word "correct." EP had to choose between the two with the goal that with rehearsal, he would be able to consistently choose the "correct" object. However, he couldn't remember which objects were correct. The experiment was repeated twice a week for months. On each day that the experiment was repeated, there were 40 pairings.

The findings were surprising. After 28 days he was choosing the correct object 85% of the time; after 36 days he was right 95% of the time. He would even turn the objects over on his own, even though he didn't remember that there would be a sticker there, as he could not recall ever doing the task.

Squire wanted to see if this was true learning - that is, that Pauly actually remembered the objects, or whether there was something else happening. He then asked EP to put all the "correct" objects in a pile. He was unable to do so. He could only select the correct object from the consistent pairings.

What was happening?

In the early 1990s, researchers at MIT had found that rats with damage to the basal ganglia had problems learning how to run a maze. The rats were put into a t-maze. There was a barrier that was raised and then they would seek out the "reward" - which was a piece of chocolate. The rats would wander through the maze, sniffing and licking at the maze, trying to determine where the food may be. Prior to the experiment, wires were implanted into the brains of the rat in order to measure brain activity while the rat ran the maze. While searching for the chocolate, the brain was highly active; there were particularly high levels of activity in the basal ganglia as well as in other parts of the brain, such as the frontal cortex.

The rats ran the maze repeatedly. The researchers found that over time, the mental activity decreased in the frontal lobe, but was still active in the basal ganglia.

Several tasks that rely on procedural memories make this transition from involving an active frontal lobe to simply an active basal ganglia. Although the actual process is complex and not fully understood, when we are learning to do a task it is often cognitive in nature. So, when I first learn to drive a car, I need to think an awful lot about what I am doing. But remember, thinking takes up a lot of energy. Our brains have adapted in a way that minimizes the amount of energy that it needs to expend. Over time, the task is no longer cognitive, but what is referred to as an associative task. But chunking together a series of movements or behaviours, the task becomes automatic. The more common word we use for associative tasks is "habits."

MRI indicated that EP's basal ganglia were undamaged.

This explains why EP could find the kitchen and the bathroom. It also explained why he was able to make breakfast and other tasks that were "routine." Of course, this also explains Squire's experiment with the pairing of objects.

It also explains another phenomenon that EP's wife reported. EP was able to take a walk around the block by himself, since his wife had taken him on a daily walk around the block after his surgery. She would even follow him around the block to make sure that he was ok, but he was able to find his way home without any problems. When he was asked from any point on his walk where he lived, he would say he didn't know, but since the task was associative - or a habit - he was able to simply walk home. However, occasionally there was a problem. If the sidewalk was being repaired and he had to leave his familiar path, EP would get lost. Returning to our example of driving a car - even when we drive a long time, bad weather or heavy traffic forces us to concentrate more. The task reverts from associative to cognitive. When this happened to EP, he did not have the capacity to solve the problem as his memory was only procedural. Once the familiar pattern was changed - as when Squire asked him to put the objects in piles - he was unable to complete the task.

The conclusions of this case study show us that memory is more complex than initially believed and that the creation of memories is not solely dependent on the hippocampus. Even with hippocampal damage, tasks may be learned - even though the individual may not remember learning the task. In the case of HM, he was taught to draw using a mirror, but he never remembered learning this. This was the result of the role of the basal ganglia.

However, the research also showed that habits need to be triggered. A cue leads to a routine. When EP was cued to play the object identification game, the routine was triggered, telling the brain to go into automatic mode.

The case study is a reminder that there are different types of memory that have different biological roots. A reminder that Atkinson & Shiffrin's Multi-Store model is overly simplified.

However, as with all case studies, there are questions about the generalizability of the findings.

Subscriber's contribution

A big thank you to Basma Wehbe for finding this great video about EP!

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team