Understanding Milgram (1963)

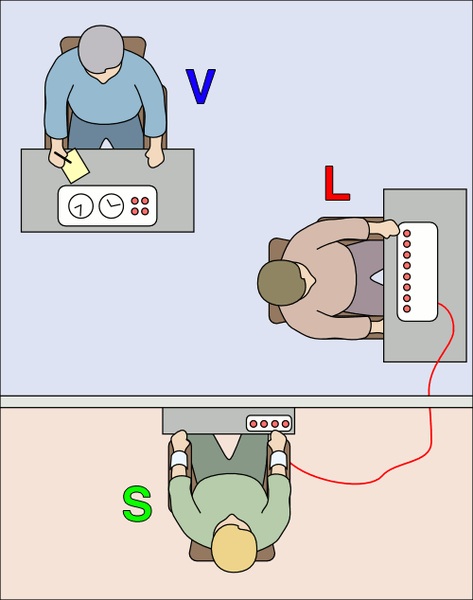

Even though obedience is not part of the IB Psychology curriculum, many students study Milgram's (1963) classic study as part of their study of ethical considerations in the sociocultural approach. The study offers students a rich opportunity for discussing issues such as undue stress or harm, informed consent, deception, anonymity, debriefing and the right to withdraw.

Even though obedience is not part of the IB Psychology curriculum, many students study Milgram's (1963) classic study as part of their study of ethical considerations in the sociocultural approach. The study offers students a rich opportunity for discussing issues such as undue stress or harm, informed consent, deception, anonymity, debriefing and the right to withdraw.

On exams and in extended essays, it is commonly argued by students that, “Milgram explained how the Holocaust was able to happen.” As a person who has devoted a good part of his life to the study and teaching of the Holocaust, it makes me sad to see that students think that it is so easy to apply a study to explain such a complex historical event.

Limitations of the Milgram experiment in explaining the Holocaust

Stanley Milgram had a deep interest in the Holocaust. His family had immigrated to the United States from Romania and Hungary after World War I. After the Second World War, relatives who had survived Nazi concentration camps stayed with the Milgram family in New York for a time. And it was the trial of Adolph Eichmann that inspired his famous experiment. So, it makes sense that we tend to associate this study with an explanation of why the Holocaust happened.

It is important to note what Milgram himself wrote about the difference between his study and the Holocaust:

The maintenance of obedience in our subjects is highly dependent on the face-to-face nature of the social occasion and its attendant surveillance. The forms of obedience that occurred in Germany were in far greater degree dependent upon the internalization of authority – to resist Nazism was itself an act of heroism, not an inconsequential decision, and death was a possible penalty. Penalties and threats were forever around the corner, and the victims themselves had been thoroughly vilified and portrayed as being unworthy of life or human kindness. Finally, our subjects were told by authority that what they were doing to their victim might be temporarily painful but would cause no permanent damage, while those Germans directly involved with the annihilations knew that they were not only inflicting pain, but were destroying human life. So, in the final analysis, what happened in Germany between 1933 and 1945 can only be fully understood as the expression of a unique historical development that will never again be precisely replicated (pp 176 – 177).

Here are some things to consider when looking at the study’s ability to be generalized to the Holocaust. You may want to ask your students to brainstorm the differences between the study and the actual historical event as a way to help them to see the problems with generalizing from laboratory research to the "real world."

- The study lacks mundane reality and ecological validity.

- The historical evidence on the spontaneity, initiative, enthusiasm and pride with which the Nazis degraded, tortured, and killed their victims is not compatible with the concept of obedience, and simply has no counterpart in the behavior that Milgram observed in his studies. (Fenigstein 1998, p 68)

- Historians have refuted Milgram’s theory of the agentic state. The theory implies that individuals “didn’t really know what they were doing” and were "simply following orders." There are, however, several examples of celebrations after the slaughters, photographs taken in which the soldiers posed with the dead, and examples of sadistic cruelty that exceed simply following orders.

- There is a widespread belief - based on statements at Nuremberg – that the Nazis had no choice but to obey orders. Historians have shown this is not the case (see Browning). The study masks the role of one’s personal choices and goals. Staub argues that the motivation to obey often comes from a desire to follow a leader, to be a good member of a group. Guided by shared cultural dispositions and the shared experience of difficult life conditions, people join rather than simply obey out of fear or respect.

- The study does not address the role of indoctrination. A long process of indoctrination is not possible within the course of an experiment. Many of the Nazi perpetrators were young men. They had been raised in a world in which Nazi values were the only moral norms they knew.

- The Jews had been dehumanized by propaganda. In the Milgram experiment the participants were led to believe that they could have been in the place of the learner. This was never part of the reality of the Holocaust.

- The study does not address the well documented “escalation of violence” that took place. In many ways, compliance techniques – such as the “foot in the door” – are a better explanation.

- The agentic state theory is unfalsifiable. This is not the hallmark of a high quality theory.

- Milgram does not explain effectively why certain authority figures command higher levels of obedience than others.

- Milgram does not effectively explain why some people find it easier to resist obedience than others. This may mean that dispositional factors do play a significant role in one’s behavior – which is not the message that usually comes from the Milgram study.

Recommended reading

Miller, Arthur G [ed] (2004). The Social Psychology of Good and Evil. The Guilford Press.

Staub, Ervin (2002). The Roots of Evil. Cambridge University Press

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team