Braun et al. (2011)

This study can be used to support the use of biological treatments and to evaluate psychological treatments and/or biological explanations for anxiety disorders. It could also be used when answering HL Extension questions on the role of animal research in understanding human behaviour, as well as Paper 1 SAQs on agonists and inhibitory neurotransmitters.

This study can be used to support the use of biological treatments and to evaluate psychological treatments and/or biological explanations for anxiety disorders. It could also be used when answering HL Extension questions on the role of animal research in understanding human behaviour, as well as Paper 1 SAQs on agonists and inhibitory neurotransmitters.

The original paper can be accessed here.

Animal models have played a pivotal role in advancing our understanding of the etiology and treatment of anxiety disorders for many years. Like others before it, this study makes use of rats. Despite being smaller and simpler, their brains share many structures and neurochemicals with our own, making it possible to extrapolate the findings to humans. This said, rats and humans exhibit anxiety in different ways. Creativity is required to find valid species-specific ways to elicit fear; countless clever designs have been developed over the years.

This study uses two anxiety-inducing mazes in order to evaluate the anxiolytic effect of diazepam (valium), a benzodiazepine that the researcher hypothesized would reduce the impact of the anxiogenic maze environment. Diazepam is a GABA agonist that helps restore calm following anxiety triggered by excitatory neurotransmitters. It binds to subunits on GABAA receptors allowing negatively charged chloride ions to flood into the postsynaptic cell, leading to hyperpolarization and decreasing the likelihood of a subsequent action potential. The effect on behaviour is thus one of sedation and a reduction in fearfulness.

This video describes the two mazes used in this study and briefly explores how they are used in experiments such as this.

Male adult rats, aged 60 and 80 days, were each observed once in either an elevated plus-maze or an elevated zero-maze. The mazes were exactly like those shown in the video (above); the plus-maze was elevated by 50 cm and the zero maze by 72 cm and 1 cm ‘curbs’ were provided on the arm areas to prevent rats from falling off and injuring themselves. All trials were conducted in the same dimly lit room. Rats were either placed in the center of the plus maze and in a dark section of zero-maze and allowed to explore for 5 minutes whilst their behaviour was filmed by an overhead camera. Mazes were thoroughly cleaned and sanitized between rats.

Dependent variables included how long the rats spent in the dark before venturing into the light (start latency), rate of head dipping (a behaviour associated with decreased fear and anxiety), percentage of time spent in the open, and the number of entries into closed areas.

The independent variable was whether or not the rats received diazepam before exploring the mazes. Rats randomly allocated to the experimental group received 5 mg of diazepam dissolved in a saline solution, while untreated control rats received the same quantity of saline solution without diazepam.

All cages were accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, were of an appropriate size, and contained wood chip bedding suitable for the species. Food and water were readily available at all times. The temperature was set at 21 degrees and the lights went on and off on a 14-hour cycle. The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

The rats placed in the zero-maze spent more time in the open zones, dipped their heads more, had lower start latencies, and entered the closed areas less than the rats placed in the plus maze, suggesting that the zero-maze did not induce as much anxiety as the plus-maze.

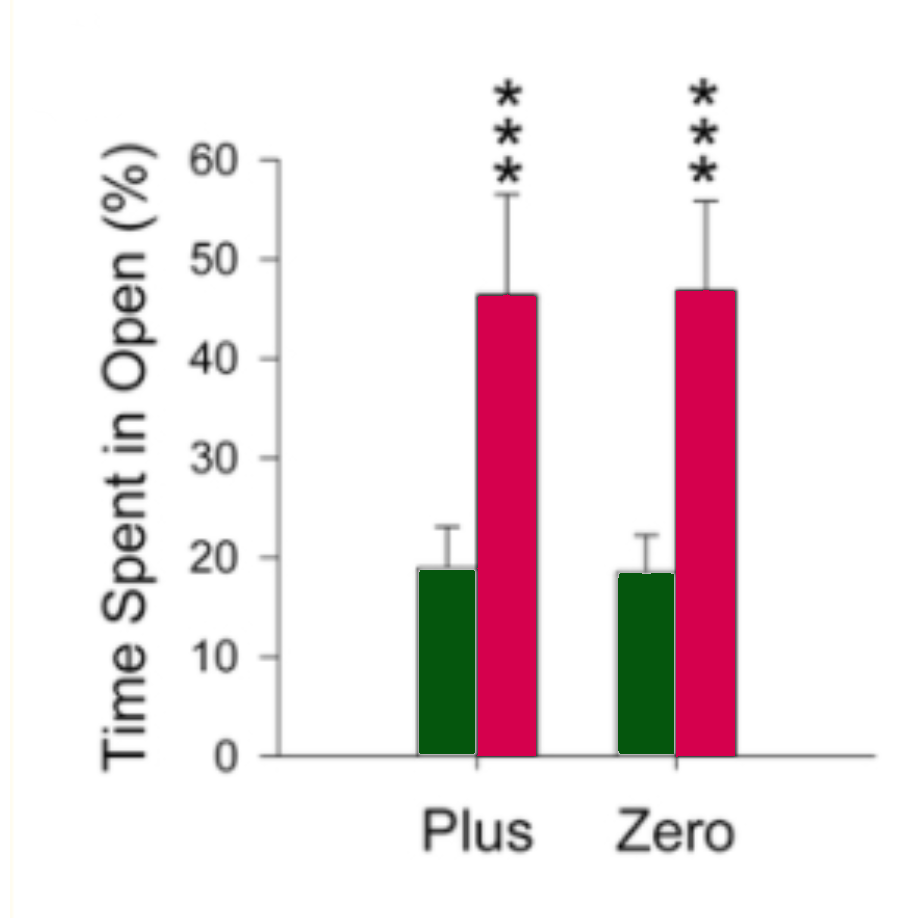

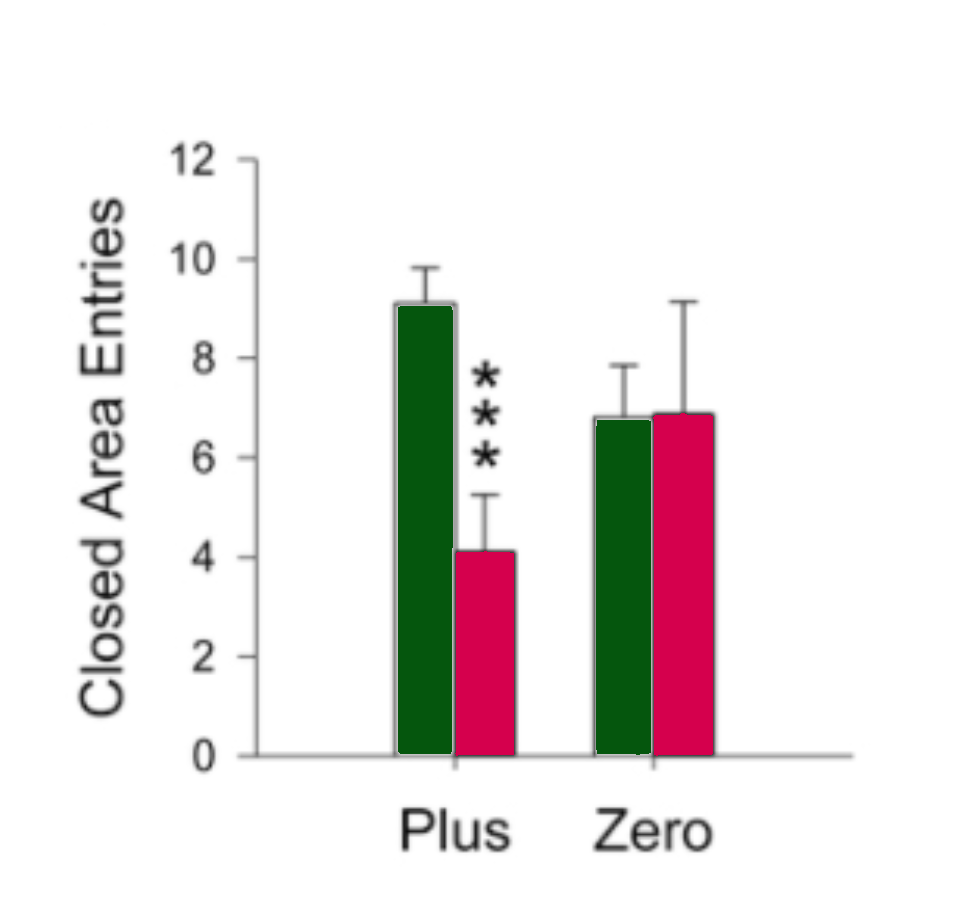

As illustrated by the two graphs below, the treated rats spent more time in the open zones of both mazes compared with the saline control rats (p ≤ 0.001), suggesting the drug had an anxiolytic effect that emboldened the rats to spend more time in the more anxiogenic areas of the mazes. Head dipping and start latencies were not significantly different in the diazepam group compared with the control group.

|

Strengths include the rats being allowed to become accustomed to the place where they would be observed a week before the study commenced. Stress resulting from an unfamiliar environment was therefore minimized. In addition, rats were only handled when their bedding needed changing, further minimizing unnecessary stress. These were important controls that increased internal validity.

The study followed all necessary ethical guidelines. For example, the rats were initially housed in pairs as they are very social animals. This said, they were separated three days before the study began in order to minimize disruption to the remaining cagemate when animals were removed for testing. Not only did this reduce stress making the study more ethical, but it also increased internal validity as stress could have affected behavior in the maze.

Limitations include the duration of the study; rats were observed once following a single injection meaning long-term effects of diazepam were not explored. For example, unpleasant side effects could increase feelings of anxiety and social withdrawal over time.

Although animal models are helpful in observing behavioural effects of certain drugs in the absence of demand characteristics or expectancy effects, this also oversimplifies the significance of taking medication in humans. In humans, the decision to take medication is one that may affect a person's sense of self. In addition, both cognitive and social factors play a role in the treatment of anxiety that is not relevant to animal models.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team