Technology, emotion, and cognition

We now live in a world of "breaking news", social media, and 24-hour news coverage. When something bad happens, our phones alert us and we are often able to watch events happen live.

We now live in a world of "breaking news", social media, and 24-hour news coverage. When something bad happens, our phones alert us and we are often able to watch events happen live.

What has the availability of this technology done to our memories? Has technology and our emotional reaction to what we see led to a higher rate of flashbulb memories? Is the constant access to information actually creating traumatic memories that could have an effect on our mental health?

Flashbulb memories

Before discussing the role of technology in flashbulb memories, we should review the important components of the theory. Although Brown and Kulik (1977) argued that surprise was the key to flashbulb memories, modern adaptations of the theory recognize that the theory is much more complex than they proposed.

Before discussing the role of technology in flashbulb memories, we should review the important components of the theory. Although Brown and Kulik (1977) argued that surprise was the key to flashbulb memories, modern adaptations of the theory recognize that the theory is much more complex than they proposed.

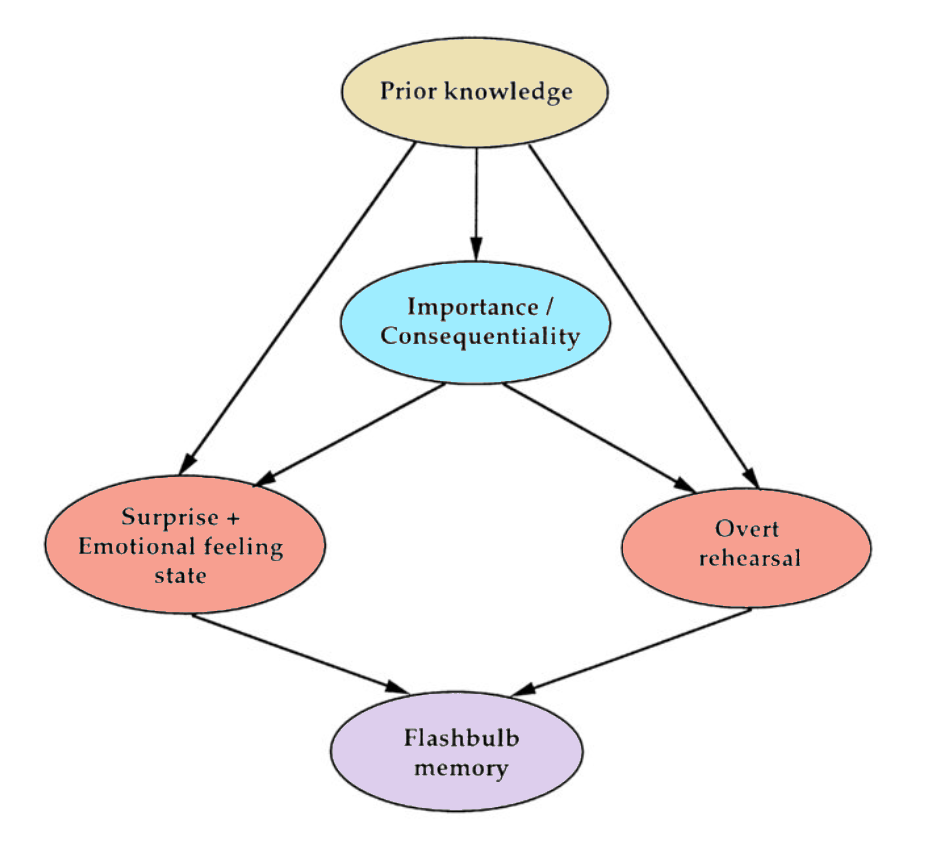

Our prior knowledge and experience play a key role in what will actually be a flashbulb memory. This helps us to determine whether an event is important to us - and it will also determine the level of surprise or emotion in our reaction to the news. If the event is important, we will discuss this with others or ruminate (think a lot about) this event, thereby engaging in overt rehearsal. It is the combination of these variables that may lead to a flashbulb memory.

The question is whether "reception context" should also be considered a variable in this model.

Does the reception context make a difference?

How we hear the news, known as the reception context, may make a difference in how we recall the news. A study by Schaefer et al (2011) wanted to see if there was a difference in memories of the 9/11 terrorist attacks depending on whether people heard the information on television or from another person. Obviously, when we first hear news from another person, visual images are absent. The researchers wanted to know just how important these visual images are in the creation of flashbulb memories.

The sample was made up of 38 students from the University of Winnipeg (mean age 20.3). They were asked to do a free recall of when they heard the news about the terrorist attack both 28 hours after the event and then again six months later. They were not told at the time of the first recall task that they would be tested again six months later.

The participants were divided into two groups: immediate and delayed viewing of television coverage of the event. Those in the immediate group (n = 27) saw the event live on television or turned on television within minutes of hearing the news. Those in the delay condition (n = 11) saw the event on television hours after being informed.

The responses were coded by two independent research assistants who were blind to the hypotheses. They coded the responses for nine canonical categories: time, location, what they were doing, informant, presence of others, clothes worn, first thought, feelings, what they did immediately thereafter.

The quantity of information provided in the initial and follow-up reports, based on the number of canonical categories and word length, did not differ with regard to reception context. However, the delayed viewing of images resulted in less elaborate and less consistent accounts over the 6-month interval.

The problem with 9/11 FBM research

The terrorist attack of 9/11 led to a lot of research on flashbulb memories. However, we have to be cautious in our interpretation of the research. Because there is no way to control the amount of media exposure over time, many of the studies have low internal validity. In the case of national tragedies, anniversaries of the tragedy receive more media coverage which then encourages overt rehearsal. 9/11 has intense media coverage every anniversary; meanwhile, personal tragic events, such as the death of a loved one, would not.

The terrorist attack of 9/11 led to a lot of research on flashbulb memories. However, we have to be cautious in our interpretation of the research. Because there is no way to control the amount of media exposure over time, many of the studies have low internal validity. In the case of national tragedies, anniversaries of the tragedy receive more media coverage which then encourages overt rehearsal. 9/11 has intense media coverage every anniversary; meanwhile, personal tragic events, such as the death of a loved one, would not.

The initial "breaking news" media coverage may play a critical role in encoding a flashbulb memory, but it may be the annual reinforcement of this memory that actually plays a role in its vividness and accuracy over time.

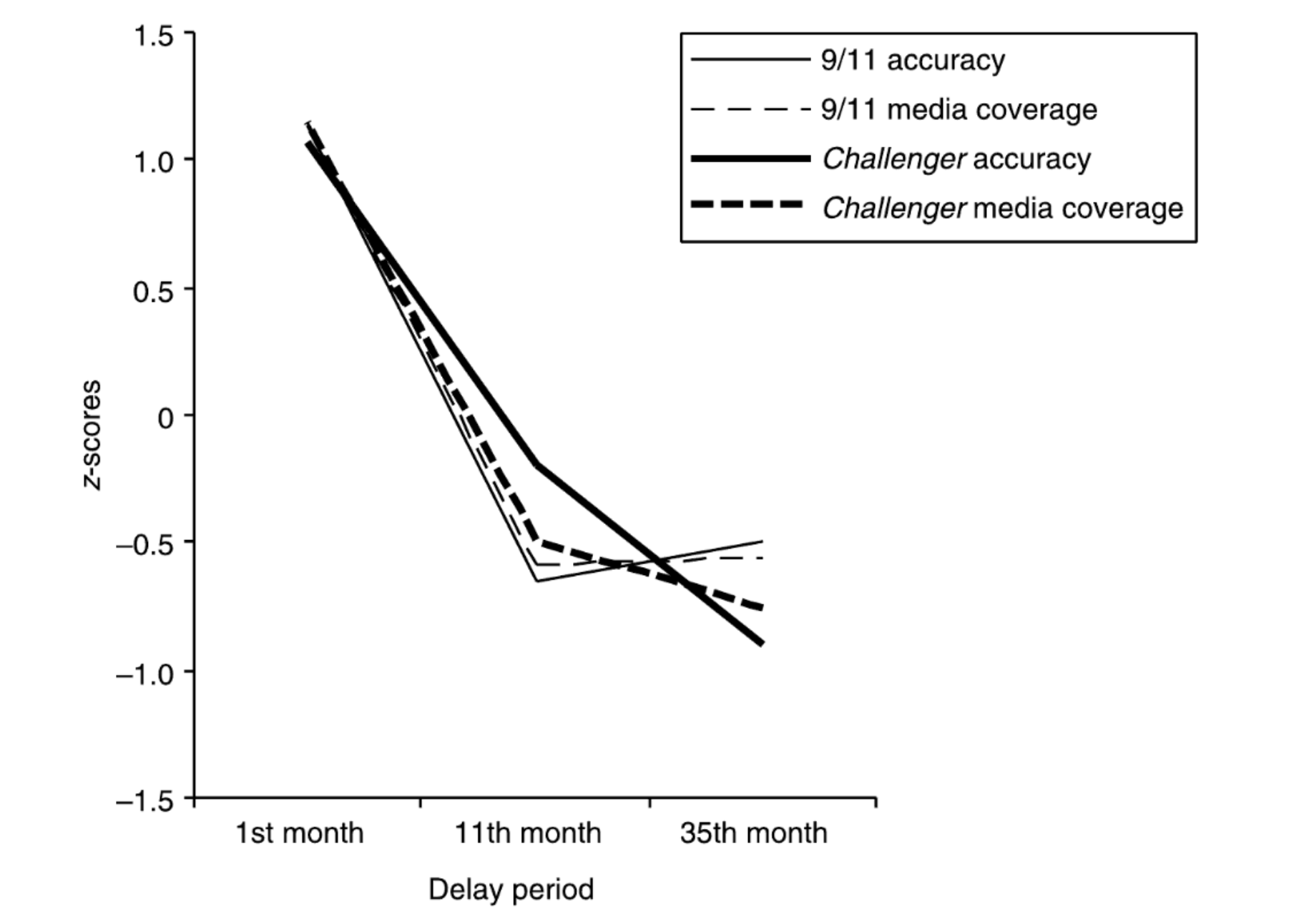

Hirst et al (2008) looked at two different national tragedies in the US - the Challenger disaster that was famously studied by Neisser and Harsh (1992) and the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The researchers wanted to see if there was a correlational between the amount of media coverage and the accuracy of their memories of the event.

As you can see from the graph to the left, there was a higher level of accuracy in the 9/11 memories; however, there was also more media coverage of the 9/11 attacks over the three years following the event.

As you can see from the graph to the left, there was a higher level of accuracy in the 9/11 memories; however, there was also more media coverage of the 9/11 attacks over the three years following the event.

Looking at the model at the top of the page, you can see that in this case, it may be that emotion played a key role in the formation of the memory - and the media's annual reminder of this emotional event results in overt rehearsal that leads to the flashbulb memory. It is not possible for researchers to say that the initial exposure to the media alone was responsible for the accuracy or vividness of the memories.

Does social media make a difference?

Berntsen (2009) argued that another potential factor in the development of a flashbulb memory is when an event activates one’s social identity. This would lead to a sense of a heightened personal significance of the event, an emotional reaction to the event, and rehearsal of that event within one’s social group. Therefore, one would expect social media sites would enhance vividness and confidence in the accuracy of memories.

As social media is still a relatively new phenomenon - and it takes time to measure the accuracy of flashbulb memories - there is very little research done on this question. Talorico et al (2017) carried out a study to see if the reception context would make a difference in the vividness and accuracy of memories of the assassination of Osama bin Laden - the mastermind behind the 9/11 attacks. She and her team compared the memories of those who learned about the assassination through television, social media, or another person.

The sample consisted of 329 psychology students. They were asked to recall how they heard about the event and what they remembered two days after the assassination and then again either 7, 42, 224, or 365 days later. After two days, the findings were that television exposure was strongest both in accuracy and the vividness of the memory. For accuracy of recall, personal communication was the weakest; for vividness, it was social media. When examining the consistency of flashbulb memory over time (up to one year later), the reception context did not make a difference.

Could the effect of technology be indirect?

When looking at the model above, could technology be responsible for another variable - international significance? Today when there is a national tragedy, the news media sends out the "breaking news" around the world. But in addition, there is also feedback - both in social media and in television news - that shows international support and a sense of solidarity which reaffirms our emotions and gives meaning to our national tragedy. Gandolphe and El Haj (2016) argue that this variable plays a key role in the creation of flashbulb memories.

When looking at the model above, could technology be responsible for another variable - international significance? Today when there is a national tragedy, the news media sends out the "breaking news" around the world. But in addition, there is also feedback - both in social media and in television news - that shows international support and a sense of solidarity which reaffirms our emotions and gives meaning to our national tragedy. Gandolphe and El Haj (2016) argue that this variable plays a key role in the creation of flashbulb memories.

On 7 January 2015 at about 11:30 am, two gunmen forced their way into the offices of the French satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo in Paris. They killed 12 people and injured 11 others. On 11 January, about two million people, including more than 40 world leaders, met in Paris for a rally of national unity, and 3.7 million people joined demonstrations across France. The phrase Je suis Charlie became a common slogan of support on social media with many people replacing their profile picture with the slogan.

Gandolphe and El Haj (2016) recruited a sample of 235 participants of French nationality and living in France to answer a web-based questionnaire. It also asked participants not to search for answers on the Internet for information about the event. The questionnaire asked about the participants' memory of the event, vividness, and predictors of flashbulb memory.

The researchers found that:

- The vividness of flashbulb recall was strongest for those that had seen more visual imagery of the event.

- Those that felt that the event was of international importance had more detailed and vivid memories.

- There was a correlation between the rating of the international importance of the event and the number of people with whom discussions were held about the attack.

In the case of the Charlie Hebdo attack, international importance seems to play an important role as the attacks led to an international debate about freedom of expression and speech, not to mention international condemnation of terrorism and solidarity with the victims - all of which was facilitated by television and social media.

Why does this matter?

It appears that technology may play a role in the creation of flashbulb memories. The images that we see in the media lead to a strong emotional response and overt rehearsal of the event. This research may play a significant role in a disorder that is linked to our inability to filter memories of trauma - PTSD. Research indicates that it is not just that we learn about an event by watching visual images on the television or computer screen, but it also matters which images we are seeing.

Ahern et al (2002) wanted to investigate the role that viewing graphic television images may play on PTSD. The researchers wanted to see if this would play a more significant role than the amount of time exposed to the media.

Their sample was made up of 1008 adult residents of Manhattan. They carried out a telephone survey in which the participants' exposure to media and symptoms of PTSD were discussed. The findings showed that specific disaster-related television images were associated with PTSD and depression. They found that participants who had repeatedly seen “people falling or jumping from the towers of the World Trade Center” had a higher prevalence of PTSD (17.4%) and depression (14.7%) than those who did not (6.2% and 5.3%, respectively).

In addition, the personal relevance of media coverage played a role in mental health. For participants who were personally affected by the attacks - for example, they lost a family member - there was a correlational between the frequency of television viewing and the prevalence of PTSD. For those participants who were not personally affected by the attacks, there was no association between the frequency of television viewing and PTSD.

Read More: https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/abs/10.1521/psyc.65.4.289.20240

Read More: https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/abs/10.1521/psyc.65.4.289.20240

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team