Zhang, Winterich & Mittal (2010)

One of the applications of cultural dimensions is in marketing. It is important to know who your customers are and how their cultural dimensions may affect the choices they make. Zhang, Winterich & Mittal (2010) wanted to see the relationship between power-distance and impulse buying. Power distance is believed to be linked to self-control, so that cultures with high power distance may display less impulsive buying.

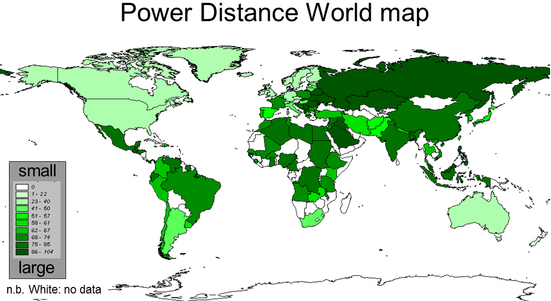

One of the applications of cultural dimensions is in marketing. It is important to know who your customers are and how their cultural dimensions may affect the choices they make. Zhang, Winterich & Mittal (2010) wanted to see the relationship between power-distance and impulse buying. Power distance is believed to be linked to self-control, so that cultures with high power distance may display less impulsive buying. Power distance is the extent to which the less powerful members of a culture expect and accept that power is distributed unequally. In other words, they accept that society is hierarchical and they have a place in that hierarchy.

In cultures with high power distance, one's position in the hierarchy is respected. Those higher up in the hierarchy have power and privileges that others do not. Titles are important and pay is often linked to status. There is also a rigid system of communication. It would not be expected, for example, that a boss would consult with his employees before making a decision, but rather with people who are of a similar position in the hierarchy. With regard to schools, teachers are seen as "authorities" in their subject.

In cultures with low power distance, hierarchies are for convenience. Independence is valued and superiors are seen as coaches and facilitators. Bosses often delegate decision-making to others and rely on team feedback. Employees expect to be consulted and not like a "top-down" approach in the workplace. Communication between individuals is informal. In schools, teachers are seen as learning coaches.

There were two studies carried out by Zhang, Winterich, and Mittal (2010).

Study 1

Participants were 97 undergraduate students from a large U.S. university. The study was an independent sample design.

The participants carried out a sentence-completion task with the goal of making power distance more salient. Participants formed meaningful sentences from sets of scrambled words. The words in each condition either provoked a high or low sense of power distance. To make sure that the feelings were salient, there were three questions at the end of the task about power hierarchies. Participants who demonstrated that, in fact, they were high PD or low PD were then asked to go on to the second part of the experiment. It was found that in 90 percent of the cases, the priming was successful.

Participants were told the following: Imagine that you are at a store and have $10 cash. You can buy as many or as few of the products listed below, or none at all. After the study is completed, one participant in each session will be randomly selected and the participants will receive whatever they have chosen in this study. If you are selected and you decide to buy nothing, you will get $10. If you are selected and decide to purchase something, you will get those items and the remaining money, totaling $10. The products were a serving of Oreo cookies for $.75, a bag of potato chips for $1.00, a bag of gummy candies for $1.50, a serving of Cheetos for $.75, a Snickers bar for $.75, and a bottle of cola for $1.50.

The researchers found that power distance predicted the amount of money spent. Those in the high PD condition spent less money and bought fewer items.

Study 2

As it could be that power distance is linked to self-control, so the list of items on the list above may seem to be unnecessary. Therefore, the researchers wanted to test to see if vice products (unhealthy) lead to higher levels of impulse buying than virtue products (healthy) in cultures with lower levels of power distance.

Participants were 170 undergraduate students from a large U.S. university. 38% of the sample was female. The tasks were the same as in the previous study, but the items to be purchased included three vice and three virtue products. The vice products were a Snickers bar, potato chips, and regular cola. The virtue products included a granola bar, apple, and orange juice. The dollar amount spent and the quantity bought served as the dependent variables.

For vice products, those with high power distance spent less. The mean spent on vice products in the high power distance group was 66 cents compared to $1.09 in the low power distance group. For virtue products, those with high power distance spent more, although this difference was not significant. For vice products, participants with high power distance bought fewer items. For virtue products, power distance did not influence the number of items bought.

The researchers showed that Power-distance influences impulsive buying of vice products, both in terms of the amount spent and the number of items purchased. If Power-distance influences unplanned buying in general, it should affect purchases of both vice and virtue products. However, this is not the case. This study supports the hypothesis that differences in power-distance result in different levels of self-control associations, which influence impulsive buying.

The study is an experiment that can be easily replicated. The ability to replicate the findings would make the findings reliable.

The researchers tested individuals on their level of power distance, rather than assuming that because they were Americans that they would have low power distance. This is important because it controls for researcher bias and the ecological fallacy.

In addition to priming the participants, the researchers gave each participant a series of questions to verify that the priming had actually been effective. This is an important control for this experiment, increasing its internal validity.

The studies used only American participants. Overall, the culture is low in power distance. This may not reflect what would happen if the study were replicated in a country with very high power distance.

The greatest criticism of this study would be its artificiality. The nature of the task under controlled conditions is not how most of us shop. The idea of getting a little extra cash and then being given a basket of goods to choose from controls variables really well, but it does not reflect what really happens when people get extra money. First, it is not clear how salient power-distance would be in the process of spending money. Would the participants show the same behaviour if they were in a grocery market? A lot of impulse buying today takes place on the Internet. This study does not take into consideration the deindividuation - that is, the sense of anonymity - that the Internet can promote.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team