Biases in thinking and decision making

Although System 1 thinking is an efficient way to process the information we receive from the world around us (meaning that it is fast and uses minimal effort) it is also prone to errors because it depends on assumptions about the world which are sensible but which do not always match the complexities of the real world which are difficult to predict! These assumptions are often referred to as heuristics – a ‘mental shortcut’; it is usually a simple rule which is applied with little or no thought and quickly generates a ‘probable’ answer.

Although System 1 thinking is an efficient way to process the information we receive from the world around us (meaning that it is fast and uses minimal effort) it is also prone to errors because it depends on assumptions about the world which are sensible but which do not always match the complexities of the real world which are difficult to predict! These assumptions are often referred to as heuristics – a ‘mental shortcut’; it is usually a simple rule which is applied with little or no thought and quickly generates a ‘probable’ answer.

Demonstrating the existence of heuristics is a good way to provide empirical support for a distinct intuitive, fast, and effortless system 1 mode of thinking. Understanding common errors in the way people think about the world can be useful as it helps us to anticipate poor decision-making and take steps to improve it.

Heuristics can result in patterns of thinking and decision-making that are consistent, but inaccurate. These patterns of thought are usually described as cognitive biases. However, it is important to note that some cognitive biases are not dependent on a heuristic – for example, the bias may be the result of an individual trying to protect self-esteem or trying to fit into a group. For this text, the term "cognitive bias" will be used as a general term to include heuristics.

There are many different examples of cognitive biases that we could discuss. We will look at three biases: anchoring bias, peak-end rule, and framing effect. You do not need to master all three of these for your exams; you should be able to discuss one or more of them.

Anchoring bias

Anchoring Bias is the tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the "anchor") when making decisions. During decision-making, anchoring occurs when individuals use an initial piece of information to make subsequent judgments.

Anchoring Bias is the tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the "anchor") when making decisions. During decision-making, anchoring occurs when individuals use an initial piece of information to make subsequent judgments.

A good example of this is when you go to buy something in the market in Marrakesh, Morocco. When you walk into the shop and see that beautiful lamp that you never knew you had always wanted, it is time to start bargaining. When you ask the shop owner for the price, the price he gives you becomes an anchor for your negotiation.

If he starts off the price at 100 USD, you will then judge the price that you pay based on that first price. If you end up paying 60 USD for the lamp, you will feel that you were successful in your bargaining. If he starts off with 250 USD, you will be thrilled if you are able to pay only 140 USD! (Wow, you must be a tough bargainer!) But the reality is that unless you are an avid lamp collector, you have no personal understanding of the value of the lamp. Your decision to buy the lamp, and your subsequent sense of satisfaction with the price, all comes down to the first piece of information you received - the original price quoted by the shop owner.

Anchoring bias is not just about shopping. Englich and Mussweiler (2001) found that anchoring bias could play a significant role in determining sentencing in courtrooms. For their study, they used 19 young trial judges (15 male and 4 female) – with an average age of 29.37 and with an average of 9.34 months of experience. They were given a scenario of a rape case, including the demand from the prosecutor for either a 34-month sentence or a 2-month sentence. When told that the prosecutor recommended a sentence of 34 months, participants recommended on average eight months longer in prison than when told that the sentence should be 2 months – for the same crime.

One of the original studies on anchoring bias was done by Tversky & Kahnemann (1974). In this study, high school students were used as participants. Participants in the “ascending condition” were asked to quickly estimate the value of 1 X 2 X 3 X 4 X 5 X 6 X 7 X 8. Those in the “descending condition” were asked to quickly estimate the value of 8 X 7 X 6 X 5 X 4 X 3 X 2 X 1. Since we read from left to right, the researchers assumed that group 1 would use "1" as an anchor and predict a lower value than the group that started with "8" as the anchor. The expectation was that the first number seen would bias the estimate of the value by the participant. The researchers found that the median for the ascending group was 512; the median for the descending group was 2250. The actual value is 40320.

Research in psychology: Strack and Mussweiler (1997)

The aim of Strack and Mussweiler's (1997) study was to test the influence of anchoring bias on decision-making. The researchers used an opportunity sample of 69 German undergraduates recruited from the university canteen at lunchtime; they were asked if they would take part in a general knowledge questionnaire. The participants answered questions on a computer screen. Each question had two components.

The aim of Strack and Mussweiler's (1997) study was to test the influence of anchoring bias on decision-making. The researchers used an opportunity sample of 69 German undergraduates recruited from the university canteen at lunchtime; they were asked if they would take part in a general knowledge questionnaire. The participants answered questions on a computer screen. Each question had two components.

In one part of the experiment, participants were given an implausible anchor to see if it would have an effect. In other words - even if we know the suggestion is outlandish, does it still have an effect on our judgment?

The participants were randomly allocated to one of two conditions. In each condition, participants were asked one of the following questions:

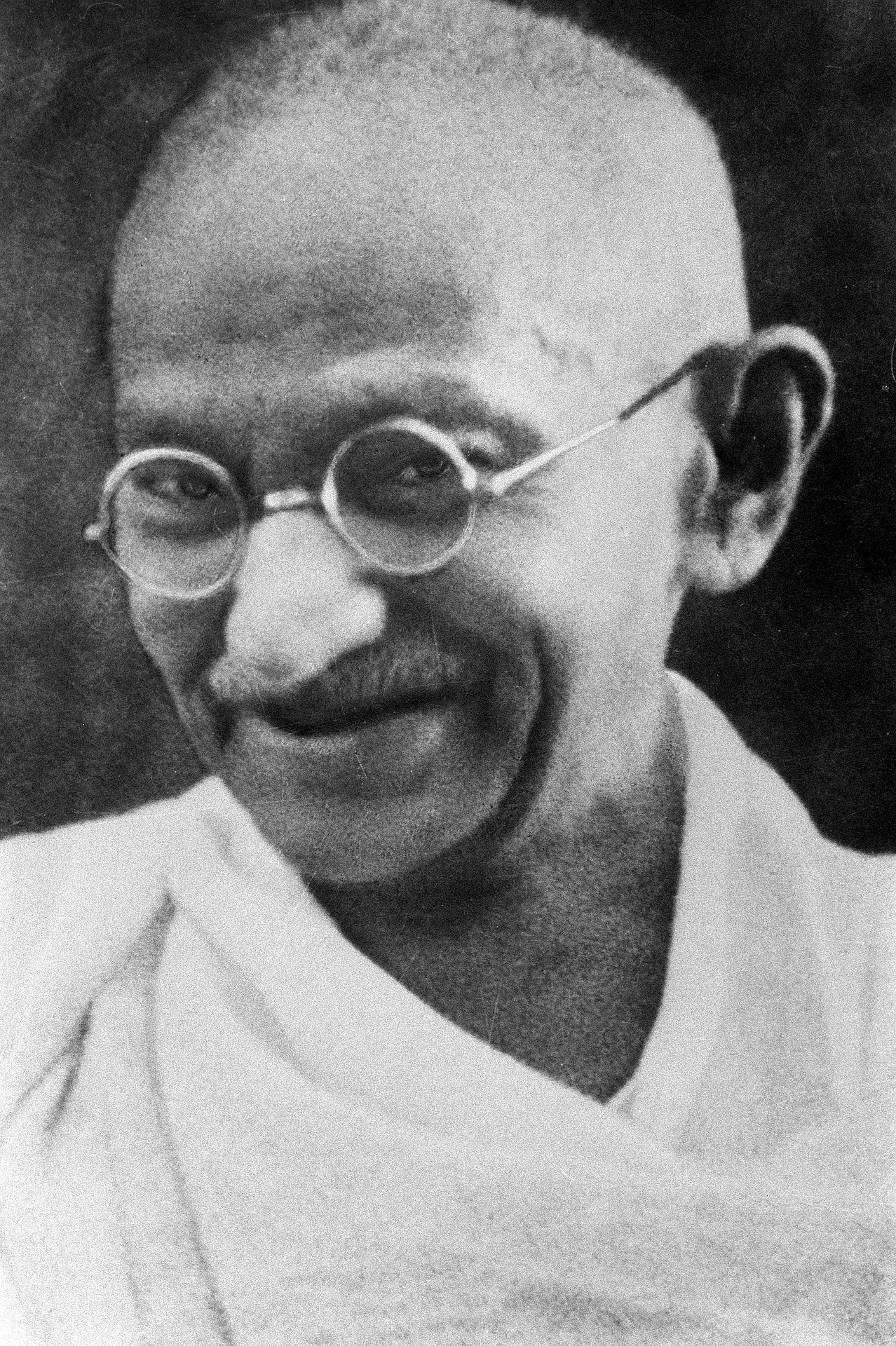

- Did Mahatma Gandhi die before or after the age of 9? [low anchor, implausible]

- Did Mahatma Gandhi die before or after the age of 140? [high anchor, implausible]

After the participants indicated their answers, they were asked to provide an estimate of how he was when he died. The actual question was:

- How old was Mahatma Gandhi when he died?

The actual answer is 78.

The data below shows the mean values for the estimated ages in response to the Mahatma Gandhi question:

| High Anchor | Low Anchor | |

| Implausible Anchor value | 66.7 | 50.1 |

Even though the anchor presented was outlandish, it clearly influenced the participants' estimates. It is interesting to note that the low anchor (9) appears to have been more influential than the high anchor (140). This could reflect the belief that the high anchor is in fact impossible, rather than implausible.

Peak-end rule

The peak-end rule is a heuristic in which people judge an experience largely based on how they felt at its peak (i.e., its most intense point) and at its end, rather than based on the total sum or average of every moment of the experience. The effect occurs regardless of whether the experience is pleasant or unpleasant. It is not that other information aside from that of the peak and end of the experience is forgotten, but rather it is not used in reaching a decision or judgment.

I caught myself using this heuristic during Prague’s annual restaurant festival. A bunch of friends and I went to dinner. On the way home, we talked about the restaurant and I said, “I wasn’t very impressed by the meal.” My friends started to laugh. They said, “John! You were smitten by the soup. You must have said five times how great it was! You were not happy that a man at the next table lit up a cigar and when you asked him if he could please not smoke, he yelled at you and told you that he was there first. But, then came the main course. You said that you thought the main course was perfectly presented and amazing both in texture and taste. You only complained that the dessert wasn’t what you expected.” Aha. I had employed the peak-end rule. First, the altercation with the other customer (a peak - or, to be honest, a trough!) influenced my perception of the evening as a negative one. In addition, the fact that I was disappointed at the end of the dinner meant that my perception of the whole dinner was rather negative. The flip side could have been true. A mediocre dinner with a great dessert can be a really positive memory.

We often use this with movies as well. Think about the films we watch. We are more likely to recommend a movie that has a slow start but an amazing ending than a movie that has an amazing start but a rather lame ending.

In one of the original studies on the peak-end rule, Kahnemann et al (1993) asked participants to hold their hand up to the wrist in painfully cold water until they are invited to remove it. With their free hand, participants recorded how strong the pain was with 1 finger being little to no pain and 5 fingers being strong pain. The researchers used a repeated measures design. The two conditions were:

Condition 1: 60 seconds of immersion in water at 14 degrees Celsius. End the end of the 60 seconds the experimenter instructed them to take their hand out.

Condition 2: 90 seconds of immersion. The first 60 seconds the same as Condition 1. At the end of 60 seconds, the researcher opened a valve that allowed slightly warmer water to flow into the tub. The water temperature rose by about 1 degree Celsius.

The participants were then told that there would be one more trial - either a repeat of Condition 1 or a repeat of Condition 2. Now, if you look at the two conditions, it makes sense that Condition 1 is the smarter choice. Both conditions have the same level of pain for 60 seconds - but after that time, Condition 1 gets a warm towel while Condition 2 gets a slight decrease in pain for an extra 30 seconds.

80% of the participants chose the second condition! This is a clear example of the peak-end rule. The fact that the second trial was longer was not taken into account by the participants (something called duration neglect). They were basing their choice on how the condition ended, rather than making an overall assessment of the pain.

So, how can we use this? This heuristic is particularly problematic in the study of relationships. Much of the research done is retrospective - for example, research on marriages that fall apart often is carried out only “after the fact.” This means that the research is open to memory distortion on behalf of the participants. In a study of why a relationship ended, the researcher may ask the participant to rate the level of disclosure in the relationship. If the couple was estranged during the last year of the relationship, it is very possible that due to the peak-end rule, the perception will be that disclosure was “always a problem” in the relationship, when in fact, the relationship may have been quite healthy for a significant amount of time that the couple was together.

Framing effect

Prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979) describes the way people choose between alternatives that involve risk, where the probabilities of outcomes are known. The theory states that people evaluate these losses and gains using heuristics. One of those heuristics is the framing effect, in which people react to choices depending on how they are presented or "framed." People prefer certain outcomes when information is framed in positive language, but prefer less certain outcomes when the same information is framed in negative language. In simple terms, when we expect success we prefer a definite win rather than a possible win, but when things look bad we will gamble on an uncertain defeat rather than a definite loss.

Research in psychology: Tversky and Kahneman (1986)

Tversky & Kahneman (1986) aimed to test the influence of positive and negative frames on decision making. The researchers used a self-selected (volunteer) sample of 307 US undergraduate students.

Tversky & Kahneman (1986) aimed to test the influence of positive and negative frames on decision making. The researchers used a self-selected (volunteer) sample of 307 US undergraduate students.

Participants were asked to make a decision between one of two options in a hypothetical scenario where they were choosing how to respond to the outbreak of a virulent disease. For some of the participants, the information was framed positively while for others it was framed negatively.

The scenario read as follows:

Imagine that the U.S. is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume that the exact scientific estimate of the consequences of the programs is as follows.

In condition 1, the participants were given the "positive frame." Their choices were the following:

If Program A is adopted, 200 people will be saved.

If Program B is adopted, there is a 1/3 probability that 600 people will be saved, and a 2/3 probability that no people will be saved.

In this condition, 72% of the participants chose Program A, whereas only 28% chose program B.

In condition 2, the participants were given the "negative frame." Their choices were the following:

If Program C is adopted 400 people will die.

If Program D is adopted there is a 1/3 probability that nobody will die, and a 2/3 probability that 600 people will die.

In this condition, 22% of the participants chose Program C and 78% chose Program D.

It is important to note that all four options, (A, B, C, and D) are effectively the same; 200 people will survive and 400 people will not.

The results clearly demonstrate the influence of the frame. Where information was phrased positively, (the number of people who would be saved) people took the certain outcome, (option A) and avoided the possibility of a loss in the less certain option (option B). By contrast, when the information was phrased in terms of people dying (a negative frame) people avoided the certain loss (option C) and took a chance on the less certain option D.

It is important to consider cultural differences in thinking and decision-making. For example, a recent meta-analysis (Wang et al, 2016) of research on loss aversion tasks like the one above has shown that people from more individualistic cultures are more risk-averse than those from a collectivist culture.

Critical thinking about cognitive biases

A quick Google search will show you that there are many more cognitive biases than the three that are discussed in this chapter. These show that we often use System 1 thinking that does not spend the time to examine carefully what our options are in order to make "informed choices." But it is difficult to measure the actual use of such biases in real-life situations. Remember the example of buying a lamp in the market. It is possible that an anchor may play a key role in determining how much you are willing to pay for the lamp - but in this naturalistic situation, there are also other factors: how much money I have to spend, the amount of time I am willing to spend bargaining, my emotional state at the time of the purchase, whether I like the shop owner or my past experience in buying lamps. And that is not a complete list.

Remember, too, that we are not very good at explaining our thinking processes. Since heuristics are often used unconsciously, our explanation as to how we decided what was the best price to pay is most likely a rationalization, rather than a true reflection of our thinking processes.

Much of the research in this chapter is done with Western university student samples under highly controlled - and rather artificial - conditions. Many of the questions given to the students would be of little interest to them and were not asked in a way that was natural. The studies lack ecological validity as well as cross-cultural support - assuming that cognitive biases are universal.

ATL: Communication

It is clear that cognitive biases can affect our decision-making - sometimes in a negative or disadvantageous manner.

First, make a list of the key decisions that are made by teenagers in your community.

Second, think about how one of the cognitive biases in this chapter may affect one of those decisions and write a cautionary tale that warns others of the pitfalls of cognitive biases in decision making.

Checking for understanding

Which of the following is not a valid criticism of Englisch and Mussweiler's study on the role of anchoring bias in courtroom sentencing?

The study used the same scenario in both conditions (high and low anchor), so extraneous variables were controlled for. Although there is always the possibility that participant variability may influence the results, this does not appear to be the case in this study. But this is also why this study would need to be replicated. With only 22 participants in each condition, the data may not be highly reliable.

Which of the following is a correct statement of the findings of Strack and Mussweiler's (1997) study of anchoring bias?

In this study, this could be because the high-value anchors were seen as too unlikely, so they had little effect on the person's judgment.

Which theory of memory could be used to explain peak-end rule?

Explanation: Peak-end rule argues that we remember information that is both distinct (peaks) and which is the most recent (end).

Which of the following statements is true regarding the framing effect?

Which of the following is not a valid criticism of Tversky and Kahneman's (1981) study of loss aversion?

The study has actually be replicated many times, so the results are reliable. But there is a question whether the two options given in each condition are really the same - and whether it is the language used, rather than the frame itself, that leads to the results that are obtained.

In Strack and Mussweiler's (1997) study of anchoring bias, the results are reported as means. What would be the best suggestion for the researchers?

The median would give us a better understanding of the data. As these are simply guesses, they are not true measures. The data is actually "ordinal" in nature. The mean may also distort the value based on outliers. Since there is more than one IV - both the size of the anchor and the plausibility of the anchor - you cannot carry out a Mann Whitney U test. The researchers carried out an ANOVA to test the significance - which was p < 0.05.

What does it mean to say that Carerre & Gottman's study was prospective in nature?

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team