GAD: Psychological treatments

Psychotherapy involves face-to-face interactions with a therapist. It is seen as more personal than drug therapy and can be individualized to meet the needs of the client. Generally, psychotherapy is more focused on addressing a person's life situation and subjective understanding of his or her psychological problems.

Psychotherapy involves face-to-face interactions with a therapist. It is seen as more personal than drug therapy and can be individualized to meet the needs of the client. Generally, psychotherapy is more focused on addressing a person's life situation and subjective understanding of his or her psychological problems.

Psychological treatments for anxiety disorders often combine cognitive and behavioural approaches in order to address how people respond to anxiety and how they think about it. Two treatments commonly used to treat generalized anxiety disorder are cognitive-behavioural therapy [CBT] and applied relaxation [AR].

Cognitive-behavioural therapies

Cognitive-behavioural therapies are based on the idea that anxiety stems from negative thinking patterns that can be changed. People with GAD may be helped to identify beliefs that, for example, they hold relating to future danger and/or threats. Then, through a series of techniques collectively referred to as cognitive restructuring, they can be encouraged to challenge and ultimately disconfirm these maladaptive beliefs, leading to a reduction in distress and physiological symptoms. For example, people may be encouraged to confront anxiety-provoking situations in order to learn that negative outcomes are not guaranteed.

Cognitive-behavioural therapies are based on the idea that anxiety stems from negative thinking patterns that can be changed. People with GAD may be helped to identify beliefs that, for example, they hold relating to future danger and/or threats. Then, through a series of techniques collectively referred to as cognitive restructuring, they can be encouraged to challenge and ultimately disconfirm these maladaptive beliefs, leading to a reduction in distress and physiological symptoms. For example, people may be encouraged to confront anxiety-provoking situations in order to learn that negative outcomes are not guaranteed.

Intolerance of uncertainty is common in people with GAD, meaning they feel unable to cope in unpredictable situations, which then become a source of anxiety. They also tend to hold positive beliefs about the value of worrying as a way of dealing with anxiety. Thus, CBT practitioners encourage people to recognize that worrying about things over which they have no control is futile whilst fostering problem-solving skills that can be used to address worries.

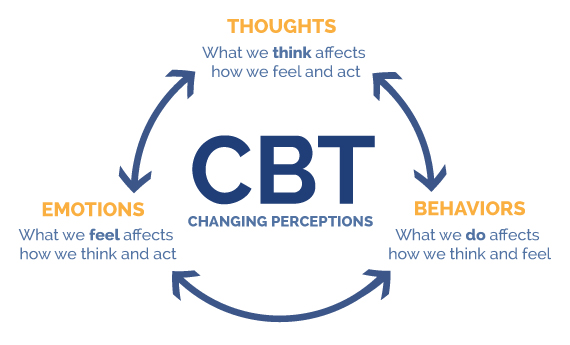

These therapies are based on the assumption that we repeat thought patterns and behaviours that serve some function or purpose; if they are rewarding in some way they will be maintained. Thus, CBT often begins with a functional analysis, where the therapist helps individuals to determine what purpose worrying serves and then helps them to meet this need in some other way. During the functional analysis, the therapist will help the person to explore the types of situations that trigger anxiety, examining the intensity of the anxiety under different circumstances and the consequences of anxiety. CBT also involves an element of psychoeducation - that is, teaching the person about the relationship between thoughts, feelings, bodily symptoms, and behaviours - and how changing the way we think can change how we feel and how we behave.

Critical thinking: Catastrophizing

One of the cognitive distortions that is common in people with anxiety disorders is catastrophic thinking. Catastrophizing is a cognitive distortion that prompts people to jump to the worst possible conclusion, usually with very limited information or objective reason to despair. When a situation is upsetting, but not necessarily catastrophic, they still feel like they are in the midst of a crisis.

The following video looks at how you might use some simple CBT techniques to try to change your thinking pattern. What do you think would be the limitations of such an approach?

The video looks at how you might use some simple CBT techniques to try to change your thinking pattern. What do you think would be the limitations of such an approach?

The approach assumes that we can be rational in our approach to our thinking and behaviour. However, there are several reasons why this may not be true - including cognitive load (too much on our minds) and ego depletion (a feeling of being overwhelmed and lacking self-efficacy). The techniques also do not account for context and environmental factors. It also focuses on a single approach to anxiety - assuming that it is soley a cognitive phenomenon. This does not account for the role of biological arousal. In that case, it may be that simply thinking differently may not be enough to stop the future onset of such panic attacks, but it may help to cope with them when they do happen.

Evaluating CBT

In a random controlled trial including 26 people with GAD, Ladouceur et al. (2000) found a significant difference in symptom reduction between people who had received CBT and a matched wait-list control group. The difference was significant both for self-reported symptoms and for ratings made by clinicians and significant others, i.e. friends and family of the participants. 77% of the participants in the CBT group no longer met the criteria for GAD post-treatment and this difference was still significant 6 and 12 months after treatment had concluded.

Another study examined the extent to which CBT was helpful in supporting patients who wished to discontinue their use of long-term anxiolytic medication. Gosselin et al. (2006) compared CBT with another psychological therapy called non-directive therapy (NDT) and found CBT to be more effective in reducing symptoms and was more likely to lead to complete remission. The sample comprised 61 people who had been using benzodiazepines for over 12 months. 75% of the CBT group managed to stop taking their medication completely following therapy, compared with only 37% of the NDT group. Results were maintained up to 12 months later, with no one returning to medication.

Applied relaxation

Applied relaxation was initially developed by Lars-Göran Öst (1987) as a treatment for phobias and panic disorder, but is now commonly used in the treatment of GAD. This therapy combines progressive muscle relaxation [PMR], a technique that allows people to achieve a state of deep relaxation, in as little as 20 - 30 seconds. The term reciprocal inhibition is helpful here; this is the understanding that it is not possible to be tense and relaxed at the same time since each response is associated with the opposing branches of the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic) that cannot be activated simultaneously.

The therapy is based on the principle that physiological, cognitive, emotional, and behavioural aspects of anxiety are interlinked, thus reducing activation in any one of these areas will lead to a reduced response in the other three areas. By this reasoning, changes in the muscular response should trigger cognitive, emotional, and behavioural changes too. Hayes-Skelton and Roemer (2013) explain that by changing our responses to anxiety cues (i.e relaxing rather than tensing our muscles) we can trigger a downward spiral into relaxation as opposed to intensifying the feelings of panic and negative thinking.

Progressive muscle relaxation

Watch the following video to learn the technique of progressive muscle relaxation. PMR is a helpful tool that you can use in your own life.

1. How does the narrator describe progressive muscle relaxation?

PMR is an exercise that reduces anxiety in the body by slowly tensing and relaxing each muscle, providing an immediate feeling of relaxation.

2. What does he say is necessary in order to achieve the best results?

Frequent practice.

3. How should you start the exercise?

By sitting or lying in a comfortable position, eyes closed, take some slow, deep breaths, try holding your breath, and as you let it out slowly imagine the tension leaving your body. Focus on the air as it fills your lungs and as it is released.

4. What does the narrator say about getting distracted while you are focusing on your breathing?

This is normal; if your mind starts to wander try and bring it back to the present moment.

5. What is the next stage of PMR? What order should you tense the muscles in?

Next, you should tense the muscles in your body one at a time, starting with your toes and feet and moving up your legs, stomach, back, shoulders, arms, hands and fingers, neck and face. Each time you tense and release you should concentrate on the tension leaving your body, whilst being sure to carry on with the deep breathing.

6. What is the final stage of PMR?

Once you have tensed each area of your body, tense all the muscles together and then let them go and feel the tension leave your body. Then open your eyes.

Öst wanted to turn PMR into a ‘portable coping skill’ that could be used away from the therapy room and in any real-life setting that might trigger anxiety. Once the person has learned the techniques explained in the video above, they can then relax muscles in increasingly large groups, thus reducing the overall time required to reach a state of deep relaxation. A final part of the exercise involves repeating the word ‘relax’ in your head as you relax your body so that the word itself becomes associated with actual bodily relaxation. In time, pairing the word and the action will mean that the word alone will be enough to make the person feel relaxed.

Having mastered PMR, the therapist will teach individuals to become aware of tension in their bodies throughout the day, e.g. while walking or working at the computer. They will be taught how to relax muscles that are not required for the activity and asked to practice body scanning as many as 15 - 20 times a day; this involves paying close attention to each area of the body in quick succession, checking for areas of tension, which should then be released.

The second important part of the therapy is helping people to identify early warning signals that indicate the onset of escalating anxiety. The individual may be encouraged to keep a diary between sessions in order to record situations that elicit negative thoughts and emotions. Once the cues have been identified, the person can be trained to initiate PMR as a coping strategy in the face of their personalized anxiety cues, stopping anxiety in its tracks.

Mindfulness

Assumes that automatic reaction patterns (habits) that are done without attention or thought can contribute to poor mental health.

Focuses on cognitive de-centering by noticing present events

Emphasis on accepting the present moment's internal events to reduce struggle with one's own thoughts and feelings

Relaxation therapy

Assumes that chronic stress and/or an overactive stress response leads to poor mental health.

Focuses on the relaxation of muscle tension.

Emphasis on changing the present moment's internal events.

Evaluating Applied Relaxation

Numerous studies have supported the efficacy of AR as a treatment for GAD, demonstrating that it is similar in efficacy to CBT. This, said, CBT may be more effective than AR over the longer term. For example, Borovec and Costello (1993) used a wide range of anxiety measures, including The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (you can find online copies of these questionnaires here and here). Twelve months after treatment, 69% of the AR group reduced their scores on six to eight of these tests by more than 20% compared with 84% in the CBT group. They also measured the percentage of people who scored within one standard deviation of the mean of a normative sample (people in the general population) on each of their eight anxiety measures, again finding that twelve months after treatment ended CBT still outperformed AR.

Allegiance effects

One problem affecting the validity of efficacy studies is allegiance effects - that is, therapists may have a personal affiliation with one type of therapy over another. For example, a therapist may have taken numerous training courses focusing on a certain type of therapy because they feel that it is the best, thus they have developed an allegiance with that particular therapy and will expect it to be more effective than other forms of therapy. Allegiance effects can reduce internal validity in efficacy studies as symptom reduction may be a consequence of differences in the way the therapist interacts with clients when delivering one type of therapy over another.

Dugas et al. (2010) attempted to combat this issue in their comparison of CBT and AR. 65 participants were randomly assigned to either the CBT group, the AR group, or a wait-list control group. Participants all received 12 one-hour sessions delivered by a psychodynamic therapist, who followed the CBT and AR manuals to ensure the therapies were delivered appropriately. She was also supervised once a week in the early stages by experts in each therapy. Choosing a therapist who was not an expert in either therapy decreased her allegiance to either therapy. Furthermore, external validity was increased as in the real world therapists are not all experts in the therapies they are delivering; often studies are criticized as the therapists are so highly trained that the results are not generalizable to general practice. In this study, people who had received CBT were much improved following treatment compared with the waiting list group, whereas those in the AR group were only marginally improved. The researchers followed up with their participants three times post-treatment, at 6, 12, and 24 months. They found that the CBT group continued to improve over the follow-up period, whereas this was not the case for the AR group. Given the additional rigorous controls in this study, it suggests that CBT really is more effective than AR in treating people with GAD.

As AR directly targets physiological symptoms of anxiety, as opposed to cognitive or emotional symptoms, Donegan and Dugas (2012) decided to re-examine CBT and AR, this time focusing specifically on the type of symptoms that were most reduced by each therapy. As expected they found that CBT was better at reducing worry-related symptoms, but AR was better at reducing somatic (bodily) symptoms. This suggests that people who are particularly struggling with the physiological effects of anxiety may find more relief from AR.

While cognitive therapy and applied relaxation appear to be the most effective treatments for GAD, Fisher (2006) argues that only 50-60% achieve full recovery following psychological treatment, meaning that these therapies provide a way of learning to cope with and manage symptoms as opposed to a cure.

ATL: The Mindfulness debate

Like AR, mindfulness-based therapy has also had mixed results. In the age of Coronavirus, the Economist magazine published an article with the title, Mindfulness is useless in a pandemic. Why is it that mindfulness is considered by some to lead to higher levels of anxiety and depression?

Like AR, mindfulness-based therapy has also had mixed results. In the age of Coronavirus, the Economist magazine published an article with the title, Mindfulness is useless in a pandemic. Why is it that mindfulness is considered by some to lead to higher levels of anxiety and depression?

Farias et al. (2020) carried out a meta-analysis of 55 studies of the use of mindfulness in adult samples. The researchers excluded research that had deliberately set out to find negative effects.

The researchers calculated the prevalence of people who experienced negative effects within each study. They then calculated the average and adjusted for the study size.

They found that about 8 percent of people who tried meditation had experienced an unwanted effect, including increased anxiety, panic attacks, and thoughts of suicide.

However, there are many studies out there that appear to support the use of mindfulness to reduce anxiety. Why do you think that there is this debate in psychology? Do some of your own research and, based on your evaluation of the research, draw your own conclusion.

Why do you think that there is this debate in psychology? Do some of your own research and, based on your evaluation of the research, draw your own conclusion.

The debate in psychology has many aspects. First, mindfulness is not a standardized practice. There are many different definitions of what is meant by "practicing mindfulness." In addition, there are some that feel that mindfulness is linked to religion and spirituality. Others do not. This may mean that the actual variable being measured is difficult to operationalize. Finally, many of the psychologists who study mindfulness also practice it. This raises the potential for researcher bias. Much of the research on mindfulness lacks a strong methodological design and has not been replicated. This does not mean that mindfulness may not be effective in the treatment of anxiety, but that we have to be cautious when drawing conclusions.

CBT clients have lower relapse rates than those treated by drug therapy. Rush et al. (1977) suggests that the higher relapse rate for those treated with drugs is because patients in a cognitive therapy program learn skills to cope with their disorder that the patients given drugs do not.

Individualized therapy can focus on the specific thinking patterns or concerns of the client. It is not a "generic treatment" like drug therapy. The client receives attention and support which results in a supportive relationship that is often absent in drug therapy.

It can sometimes be the case that the symptomology of the disorder is so strong that it negatively affects the ability to carry out psychological therapy.

CBT does not address the past experience of the client nor does it address the potential biological nature of the disorder. Thus, CBT may be focusing more on current symptoms than on the causes of the disorder.

There are some ethical concerns about the use of individualized therapies. In directive therapies, the therapist is making judgments about the "rationality" of the client's thinking.

Psychological treatments take a lot of time to start showing improvement.

There are some concerns that individualized therapy is based on individualistic and not collectivistic cultural norms. Research needs to be done to determine the extent of the cross-cultural application of the therapy.

Checking for understanding

Which of the following is not specifically related to GAD?

Answer: Thought-action fusion is more commonly associated with obsessive compulsive disorder although this is not to say that people with GAD may not occasionally present with similar thought patterns. The other three options are all typical aspects of the GAD diagnosis.

Which of the following is not part of cognitive-behavioral therapy?

Answer: Progressive muscle relaxation is part of applied relaxation, not CBT. The other three options are all standard aspects of CBT for GAD.

What is the purpose of functional analysis?

Answer: Functional analysis serves to reveal the purpose of worry in terms of when it happens and what it achieves. The disconfirmation of false beliefs is part of cognitive restructuring, teaching about the links between thoughts, actions, emotions and bodily symptoms is part of the psychoeducation element of CBT. Achieving a state of deep but rapid relaxation is a primary goal in AR therapy.

What is the correct term for a control group that does not undergo treatment at the same time as the experimental group but will be treated in the future?

Answer: Wait-list control groups are commonly used in efficacy studies for ethical and methodological reasons. From a ‘protection from harm’ point of view, it is not ethical to withhold a treatment that the researchers believe will relieve symptoms. But from a methodological point of view, a control group who do not receive therapy is important in order to determine the extent to which symptoms may change simply as a consequence of the passing of time. The waitlist control group may or not be monitored as part of the study when they start receiving treatment at a later date.

Which of the following was not a way of increasing internal validity in Ladouceur et al. (2000)?

Answer: Ladouceur et al. (2000) was a random control trial meaning participants are randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups, thus eliminating the effects of participant variability as a confounding variable. Allegiance effects were not controlled for in this study, this was part of the AR study by Dugas et al. (2010). Ladouceur et al. (2000) did use triangulation, in that they collected data about symptoms reduction from the participants, the clinicians and the significant others thus enhancing internal validity. This leaves the correct answer to this question. The follow-up study, whilst important for assessing relapse and remission rates is not a way of increasing internal validity, which is the extent to which changes in the DV are a consequence of the IV.

Gosselin et al. (2006) compared CBT and which other form of treatment for generalized anxiety disorder?

Answer: Non-directive also known as person-centered therapy was the other form of therapy that was used in the Gosselin et al. (2006) study. This is where the therapist guides the client to find their own answers to their problems, rather than actively challenging and setting tasks to help with specific goals.

Which of the following terms relates to Applied Relaxation?

Answer: Decentering and acceptance are part of mindfulness, which is increasingly used as part of cognitive therapy with variable results. Reciprocal inhibition is an important principle relating to AR, and refers to the fact that we cannot be tense and relaxed at the same time as these states are regulated by different branches of the nervous system which cannot both be active at the same time.

In Dugas et al (2010) the therapist was trained in which type of therapy?

Answer: The therapist in this study was trained in psychodynamic therapy, meaning this was the therapy to which she had the greatest allegiance. This meant she should not feel more aligned with either of the therapies that she was delivering in the research study, thus controlling for allegiance effects that might otherwise have decreased the internal validity of the study’s findings.

According to Rush et al. (1977), why do drug treatments lead to higher relapse rates than psychological therapies?

Answer: Rush et al. (1977) believed that psychological treatments were less likely to result in relapse than drug treatments as they teach people coping skills. The other answers are all important considerations when evaluating both biological and psychological treatments though. For example, it is certainly true that side effects can reduce compliance in people taking medication and this needs careful monitoring on the part of the practitioner. The severity of symptoms is an important confounding variable when looking at relapse rates and many studies ensure groups are carefully matched so this does not decrease their internal validity. A final issue in efficacy studies is that participants must ultimately choose the therapy they wish to trial and socio-cultural differences between people, which affects the treatment pathway that they choose, may also affect their experience of remission and relapse.

What percentage of people do not achieve a complete remission following psychological treatment for GAD according to Fisher (2006)?

Answer: Fisher (2006) suggests that 50-60% of people with GAD experience complete recovery following treatment with psychological therapies, this means that 40-50% do not achieve complete remission. These people may be helped via the use of drug treatments or other strategies including important lifestyle changes, support from indigenous healers and religious leaders, or spiritual/alternative therapies.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team