Is Broca still relevant today?

There are many classic studies in psychology that are now getting quite old. One such study, by Paul Broca, is 160 years old. The original study did have an impact on what we understand about language and the brain, but considering how much we have learned about the brain in just the past 10 years, this study is not the best choice for an IB exam. In fact, the IB has repeatedly given feedback that studies from the 19th century should not be used on exams. They do not earn up to full marks unless they demonstrate a modern understanding of the behaviour being discussed. So, what if you really like Broca? What should you be able to discuss in order to access top marks in an essay on localization of function?

There are many classic studies in psychology that are now getting quite old. One such study, by Paul Broca, is 160 years old. The original study did have an impact on what we understand about language and the brain, but considering how much we have learned about the brain in just the past 10 years, this study is not the best choice for an IB exam. In fact, the IB has repeatedly given feedback that studies from the 19th century should not be used on exams. They do not earn up to full marks unless they demonstrate a modern understanding of the behaviour being discussed. So, what if you really like Broca? What should you be able to discuss in order to access top marks in an essay on localization of function?

The original study

The following is a translation of the original study of Tan. As you can see, the original publication was very short and lacked many details.

Mr. Broca, on the occasion of this report, presented the brain of a fifty-one-year-old man who died in his care at Bicêtre hospital, and who had lost the use of speech for the past twenty-one. As the specimen is to be deposited at the Dupuytren museum, and the complete report is to be published in the Bulletin de la Société anatomique, we restrict ourselves to giving here a short summary of the case, which is quite similar to some of those given by Mr. Auburtin at the last meeting.

When the patient was admitted to Bicêtre, at the age of 21, he had lost, for some time, the use of speech; he could no longer pronounce more than a single syllable, which he ordinarily repeated twice at a time; whenever a question was asked of him, he [p. 236] would always reply tan, tan, in conjunction with quite varied expressive gestures. For this reason, throughout the hospital, he was known only by the name of Tan.

At the time of his admission, Tan was perfectly able-bodied and intelligent. After about 10 years, he began to lose the movement of his right arm, then the paralysis spread to the lower limb of the same side, so much so that, for six or seven years, he continually stayed in bed. For some time it has been reported that his sight was weakening. Finally, those who have had a particularly close relationship with him have remarked that his intelligence has dropped off a lot in recent years.

April 12, 1861, he was transferred to the care of hospital surgery for an immense, widespread gangrenous inflammation [phlegmon], which affected the full extent of the right lower limb (the paralysed side), from the heel up to the buttock. It was then that Mr. Broca saw him for the first time. The study of this unfortunate, who could not speak and who, being paralysed in the right hand, could not write, presented some difficulty. It was noted, however, that general sensation was maintained; that the left arm and leg obeyed the will; that the muscles of the face and of the tongue were at no point paralysed, and that the movements of this last organ were perfectly free.

The state of intelligence could not be exactly determined, but there is evidence that Tan understood almost everything that was said to him. Not able to express his ideas or his desires other than by the movement of his left hand, he often made incomprehensible gestures. The numerical responses were the ones he made best, by opening or closing his fingers. He would indicate, without error, the time on a watch to the second. He knew exactly how many years he had been in Bicêtre, etc. [p. 237] However, many questions to which a man of normal intelligence would have found the means to respond by gesture, remained without intelligible response; other time the response was clear, but did not answer the question. Undoubtedly, then, the intelligence of the patient had been affected to a great degree [atteinte profonde], but he maintained certainly more of it than was needed for talking.

The patient died April 17, 1861. At the autopsy, the dura mater was found to be thickened and vascularised, covered on the inside with a thick pseudo-membranous layer; the pia mater thick, opaque, and adherent to the anterior lobes particularly the left lobe. The frontal lobe of the left hemisphere was soft over a great part of its extent; the convolutions of the orbital region, although atrophied, preserved their shape; most of the other frontal convolutions were entirely destroyed. The result of this destruction of the cerebral substance was a large cavity, capable of holding a chicken egg, and filled with serous fluid. The softness had spread up to the ascending fold of the parietal lobe, and down to the marginal fold of the temporal-sphenoidal lobe; finally, in the depths, [it spread to] the region of the insula and the extraventricular nucleus of the striate body; it was the lesion of this last organ which was responsible for the paralysis of the movement of the two limbs of the right side. However, it suffices to cast a glance at this paper to recall that the principal home and the original [primitif] seat of the softness, is the middle part of the frontal lobe of the left hemisphere; it is there than one find the most extensive lesions -- the most advanced and the oldest. The softness progressed very slowly to the adjoining parts and one can regard it as certain that it was there for a very long period. [p. 238] during which the illness did not affect the convolutions of the frontal lobe. This period probably corresponds to the eleven years that preceded the paralysis of the right arm, and during which the patient had maintained his intelligence, having lost nothing other than speech.

All this permits, however, the belief that, in the present case, the lesion of the frontal lobe was the cause of the loss of speech.

Modern understandings

The bottom line is - today Broca's findings have been challenged; some would argue that they have been refuted. Recent findings with language-impaired patients have suggested that the Broca's area may not be as central to language production as believe and that other regions may play an essential role in speech production.

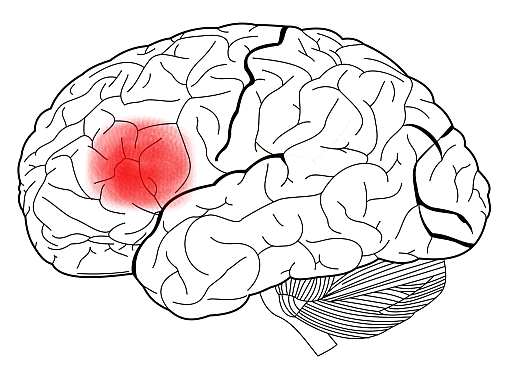

To start, here is a quick overview of the Broca's area.

Obviously, when Broca did his research, he did it on a very small sample. There were two historic patients on which the claims for the role of Broca's area were based. In addition, the only way he had to map the brain was through post-mortem research, which is rather limited compared to the technology that we have today.

Wernicke (1874) suggested that the Broca's area contains motor memories - that is, memories of the sequences of muscular movements that are needed to articulate words. But Broca's aphasia is more complex than this. There are three major speech deficits that are produced by legions in and around the Broca's Area: agrammatism (the inability to produce grammatically correct speech), anomia (the inability to name persons or objects) and articulation difficulties. These problems cannot be explained by Wernicke's original conclusions.

In addition, Dronkers (1996) has found that apraxia - the inability to produce speech because of the inability to control the movement of the tongue, lips, and throat - is due to damage to the insular cortex, not the Broca's area.

Another study appears to show the role of genetics in language development. Watkins et al (2002) studied three generations of the KE family, half of whose members are affected by a severe speech and language disorder caused by mutation of a single gene found on chromosome 7. The mutation appears to cause abnormal development of the caudate nucleus and the left inferior frontal cortex, including Broca's area.

Dronkers et al (2006) examined the brains of these two famous patients using a high-resolution MRI. It appears that the absence of speech cannot be attributed to lesions in the Broca's area alone. In fact, the region which was damaged in the patients is not precisely the same region that we identify as Broca's area. These findings are important; they may help to explain why damage limited to the Broca's Area does not appear to produce Broca's aphasia. It appears that the damage must extend to the surrounding regions of the frontal lobe and the underlying white matter.

So, the bottom line is that it appears that Broca oversimplified the process of speech production and that the argument for localization of function is a rather oversimplified approach to such a complex human behaviour.

Exam preparation

It is not recommended that you use Broca's study of Tan for an SAQ since there is very little detail about the actual procedure.

If you choose to prepare Broca for an essay on localization of function, you should consider the following:

- Explain the limitations of the research - which include not only a small sample size, but a lack of modern technology and a modern understanding of the brain.

- Be able to clearly explain the functions of the Broca's Area.

- Be able to explain at least one study that challenges Broca's conclusion about the localization of language production in the Broca's area.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team