The Nature of Science

What is the Nature of Science?

I received an e-mail from a student (not someone I teach) which included the following:

"Since I am new to the IB, could you tell me what has been the toughest topic for students generally in the exams over the past few years, and also, from a quick look at the syllabus, what is this nature of science business?”

It is not only students who wonder, “What is this nature of science business?” Many teachers are not clear either.

So what exactly does the IB mean by the Nature of Science? There is seven page description of it given in the current (2014) Subject Guide and you should certainly read this (pages 6 to 12). Essentially it covers five key points and lists sub-headings under each of these five points.

1. What is science and what is the scientific endeavour?

2. The understanding of science

3. The objectivity of science

4. The human face of science

5. Scientific literacy and the public understanding of science

It is then followed by two short sections one on ‘The Nature of Chemistry’ and one on 'Science and Theory of Knowledge’.

When I first saw it I thought that NOS is simply Theory of Knowledge as applied to the Natural Sciences and in our case to chemistry in particular. To confirm whether I was right or not I showed what is written by the IB about the Nature of Science to senior examiners, authors and teachers of TOK. All of them agreed with me that the Nature of Science is essentially the application of TOK to the Natural Sciences. One of them has put it eloquently:

"What is written in the Nature of Science document are areas that could/would be looked at in TOK in a specific sense, whereas what is written in the TOK document is very generic. Pretty much everything in the nature of science document could be explored from a TOK perspective, but the way it is looked at would probably be formulated into questions which are not how this document is set out. For example, 1.7 in a TOK sense might be set out as the question: "To what extent does doubt play a role in the acquisition of knowledge in the natural sciences and how does this effect reliability and validity in this subject area?" 1.9 might become: "Why is it important to distinguish between hypotheses, laws and theories in the natural sciences and what do these distinctions tells us about knowledge in these areas?" I would suggest that from a teacher's perspective there is no difference between the two sections. If you were to re-label "nature of science" as "nature of scientific knowledge" then, in my view, this would be a one sentence description of what we do in TOK when we look at the natural sciences."

Another, an author of a highly respected book on TOK, simply said,

“In my book, this is TOK! If not, I would like someone to explain the difference. In one sense, I don’t see any problem with this. TOK is supposed to complement the focus on methodology & critical thinking that should naturally happen in subject areas. Historians talk about primary and secondary sources and we do that in TOK too. However, I think it would create a lot of confusion if the Nature of Science and the Science element of TOK are quite different. If someone wants to claim that, it is incumbent on them to explain in detail how the two differ.”

What I infer from all of this is a teacher in the past who incorporated TOK into their chemistry teaching can carry on doing exactly that to cover NOS. Where there is confusion is that NOS can be assessed whereas TOK will not be assessed. The problem with this is that there is considerable overlap between what is written for NOS (assessable) and TOK (not-assessable). To give one example, in 1.1 under TOK it states “Lavoisier’s discovery of oxygen, which overturned the phlogiston theory of combustion, is an example of a paradigm shift. How does scientific knowledge progress?” and yet in Topic 2.1 under NOS it states, “Paradigm shifts—the subatomic particle theory of matter represents a paradigm shift in science that occurred in the late 1800s.” From this it seems quite clear that the concept of paradigm shifts can be examined. (Note that in the updated version of the Guide published in February 2018 the statement 'Lavoisier’s discovery of oxygen' has now been changed to just 'The discovery of oxygen' as Lavoisier did not actually discover oxygen - he only realised its significance).

.jpg)

The human face of science

Einstein’s paradigm shift is NOS so can be assessed; Lavoisier’s paradigm shift is TOK so cannot be assessed!!!!

So what is the best way to incorporate NOS into your teaching?

My suggestions are:

- Know what is written about the Nature of Science on pages 6-12 of the 2014 Chemistry Guide.

- Make sure you understand how TOK works and how it can be applied to chemistry. You can read about this in the TOK section under IB Core. You can then provide examples which will help students when it comes to writing their TOK essay or delivering their seminar. (This is because TOK examiners tend to give credit for relevant specific examples taken from subjects studied by students to back up their arguments. Too often they just see students using the typical examples provided by TOK class teachers who of course cannot be experts in all the different IB disciplines.). There are many good examples of TOK/NOS as it relates to chemistry in Peter Wother's book Antimony, Gold & Jupiter's Wolf which I've reviewed in How the elements were named.

- Look at what is written for NOS at the head of each sub-topic in the guide and read what I have written to supplement this on the relevant page for each sub-topic. Often what is written under 'Pause for thought' at the start of each sub-topic relates to the Nature of Science. Also look at what is written for each topic under the heading “Incorporating IM, TOK, Utilization etc.”.

- Use the accompanying glossary of key terms and concepts. If students (and teachers) know what is meant by key terms such as ‘Paradigm shift’ and Occam’s razor’ and can illustrate them with examples they will be well-prepared to answer NOS questions.

- Practice with past NOS questions. Certain areas of NOS such as falsification and the need for repeatable and accurate data will crop up time and time again.

Possible discussion on ‘The scientific method’

To initiate a discussion with your students on the Nature of Science before bringing in the ideas of Popper and Kuhn etc. and the importance of serendipity you might like to show the 14 minute TEDx talk given by a theoretical physicist, Dr Teman Cooke, entitled “The scientific method is crap”.

In this talk he defines what he sees as the scientific method as being linear in nature that follows the sequence

Step 1. Identify a problem

Step 2. Do some research

Step 3. Form a hypothesis

Step 4. Do an experiment with independent and dependent variables to test your hypothesis

Step 5. Analyse your data

Step 6. Draw a conclusion

You may well recognise this as a basic formula used by many students for both their IA and EE in chemistry.

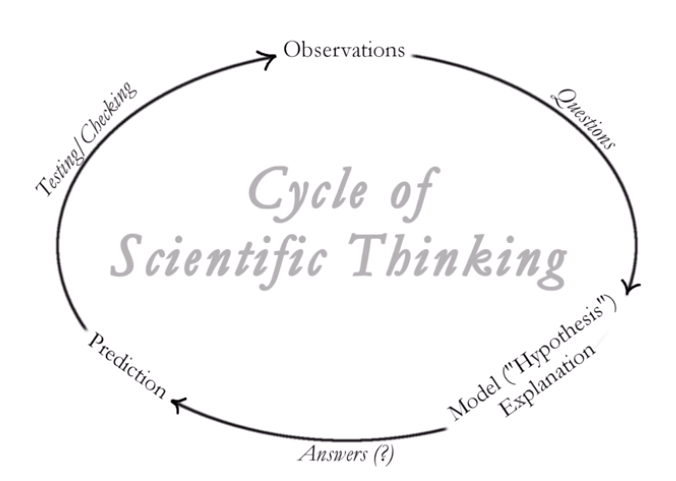

He then goes on to talk about the ‘Cycle of scientific thinking’.

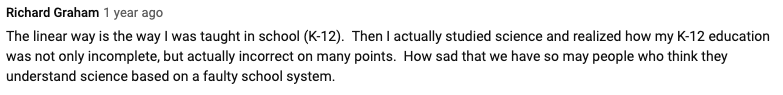

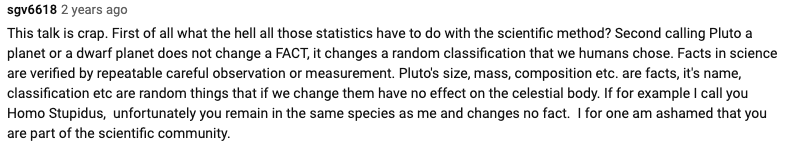

To stimulate discussion you might like to refer to some of the comments posted below the YouTube video, For example:

A good resource for NOS activities

It is well worth looking at a website developed by Oliver Canning who now teaches Chemistry and Theory of Knowledge at TASIS, England having previously taught at the United World College of S.E. Asia in Singapore. It has many activities on the Nature if Chemistry that you can do with your students.

![]() The Nature of Chemistry by Oliver Canning

The Nature of Chemistry by Oliver Canning

(You may find that this link does not load from this site as it is not secure in which case type http://www.natureofchemistry.com/ separately into your browser and it should work.)

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team