Determining the Mr of an unknown gas

A real problem for your students to solve

One of the good things about this experiment is that it gets students to solve a real problem. It also addresses one of the mandatory laboratory component areas listed under Topic 1.3 Reacting masses and volumes. 'Obtaining and the use of experimental values to calculate the molar mass of a gas from the ideal gas equation'. In the ‘real world’ chemists often know what the problem is - the challenge is to find a solution. One of the best experiments I like to do is to simply ask the students to find the relative molecular mass (Mr) of the gas in the laboratory. Clearly this could be adapted to find the relative molecular mass of any unknown gas that you give them. In my laboratory the gas is propane. If you are on the mains gas supply it is likely to be methane and if you use a gas cigarette lighter it will be butane. All of these are hydrocarbons so you must stress that whatever method they come up with must not involve a spark or naked flame due to the risk of explosion. If you are worried about this you can always use an unmarked cylinder of carbon dioxide as your gas supply.

This experiment is good because students are challenged to find their own method using what is available in the laboratory and it covers much of the chemistry in Topic 1: Quantitative chemistry. There are several different ways in which students solve the problem. Most of them involve finding the volume of a known mass of the gas at a known temperature and pressure then using the General Gas equation pV = nRT.

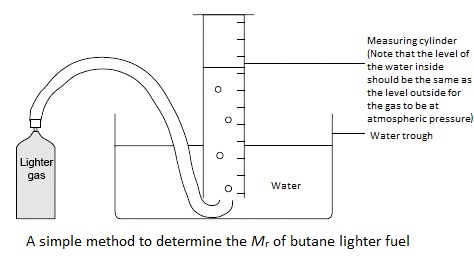

If students use a cigarette lighter probably the simplest way is to take the mass of the lighter containing the gas, release some of the gas and collect the volume over water then remass the lighter to find how much gas was released. This method cannot be used for the laboratory gas supply as the mass of the ‘container’ cannot be measured before and after.

What my students usually do is to take an empty 100 cm3 gas syringe and fit a piece of tubing with a clamp on it at the nozzle. They can then find the mass of the empty syringe with the plunger closed. Then they connect the gas tap to the piece of tubing and allow exactly 100 cm3 of gas into the syringe before closing the clamp and then taking the mass of the syringe containing the gas to give the mass of 100 cm3 of the gas. They can measure the temperature with a thermometer and the pressure with a barometer (or simply assume it is 1 atmosphere). The great thing about this experiment is that they usually get the wrong answer! My gas is propane with a relative molar mass of 44. They usually get about 15 and therefore assume the gas is methane and explain the slight error as being due to the uncertainty associated with the small mass difference. I then tell them to record the mass of the syringe empty with the plunger closed and then with 100 cm3 of air. They will find there is absolutely no difference due to Archimedes Principle! To get the correct answer for the laboratory gas they need to include the relative molar mass of air which is about 28.8 (assuming air is 80% N2 and 20% O2) which will give them an answer very close to 44. I then ask them why they used a gas syringe and they usually say because the volume is already known.

In fact a more accurate method and even simpler method is to use the biggest flask they can find. Get them to refine their experiment by first weighing a large dry flask together with a bung containing just air then in a fume cupboard displace the air with the propane and reweigh. Repeat this until there is no further change in mass (i.e. all the air has been displaced) then fill the flask with water and pour the water into a measuring cylinder to give the exact volume of the flask. If the flask has a volume greater than about one litre then a very accurate result can be obtained as the mass of gas is sufficiently large to minimise uncertainties. In fact, why use a flask? A large plastic drinks container is just as good and shows that you can do some very accurate chemistry with very simple ‘supermarket’ materials - providing of course that you have an accurate balance (see image on right).

In fact a more accurate method and even simpler method is to use the biggest flask they can find. Get them to refine their experiment by first weighing a large dry flask together with a bung containing just air then in a fume cupboard displace the air with the propane and reweigh. Repeat this until there is no further change in mass (i.e. all the air has been displaced) then fill the flask with water and pour the water into a measuring cylinder to give the exact volume of the flask. If the flask has a volume greater than about one litre then a very accurate result can be obtained as the mass of gas is sufficiently large to minimise uncertainties. In fact, why use a flask? A large plastic drinks container is just as good and shows that you can do some very accurate chemistry with very simple ‘supermarket’ materials - providing of course that you have an accurate balance (see image on right).

Why this is a good experiment

This practical covers some excellent chemistry as all the uncertainties can be worked out and the result obtained compared with the known literature value to give the percentage error. It does not form part of the internal assessment of course, but it does tick one of the mandatory areas. It also helps students to fully understand the underlying chemistry and thus help them to solve problems set on this topic which may appear in the Experimental work questions on Section A of Paper 3 in the external examination.

You can also bring in some TOK. Twice in my career students have solved the problem in less than five seconds. They looked under the bench and saw that the gas was coming from a bottle labelled propane and hence deduced immediately that the answer was 44. Too often we expect students to solve the problem by an accepted method rather than thinking laterally to give the simplest solution. Of course when they did this I then said that they should now devise a method to verify that their result is correct.

You can go on to ask students how their method could be adapted to find the molar mass of a volatile liquid. Historically this was done by the Victor Meyer method where a known mass of the liquid is rapidly vaporised to displace a volume of air which can then be collected over water and measured at room temperature and pressure. A more modern method is to encase a gas syringe with a rubber seal in an oven at a temperature considerably above the boiling point of the liquid. A known mass of the volatile liquid is then injected into the gas syringe and the volume, pressure and temperature measured.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team