5. The Tokugawa Shogunate's rule in Japan

The Tokugawa Shogunate, also known as the Tokugawa Bakufu controlled Japan between 1603 and 1868. Society was characterised by a strict social order and isolation from the rest of the world. But during this time of peace, the economy grew rapidly; this caused changes in the distribution of wealth which in turn placed huge strains on the political and social structures of Tokugawa Japan.

Guiding questions:

What were the origins of the Tokugawa Shogunate?

How was society organised under the Tokugawa Shogunate?

Why did the changes to economy and society during the Tokugawa rule lead to discontent?

1. What were the origins of the Tokugawa Shogunate?

Starter: Watch the first two minutes of this video to get an introduction to the start of Tokugawa rule and the key sections of society.

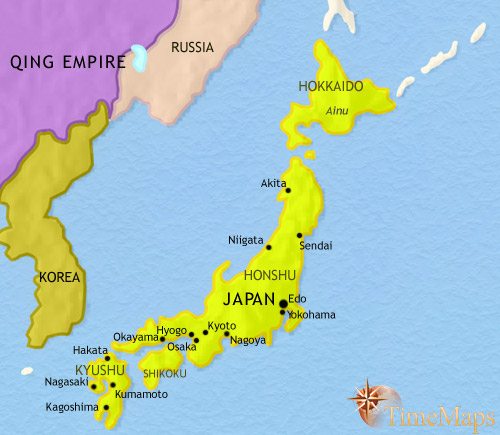

As you will have seen from the video above, the period from the mid-fifteenth to the mid-sixteenth century was one of civil war and is known as the Warring States Period. Japan during this time was a feudal society and in almost continuous warfare. There was no strong central government; rather power lay at the local level. The most important institution was the small feudal state dominated by the local lord or daimyo and his warriors or Samurai. Gradually, however, the daimyo started to join together into regional groupings and from 1570 to 1600, there was a power struggle between these regional groupings to see who could gain control over the whole country.

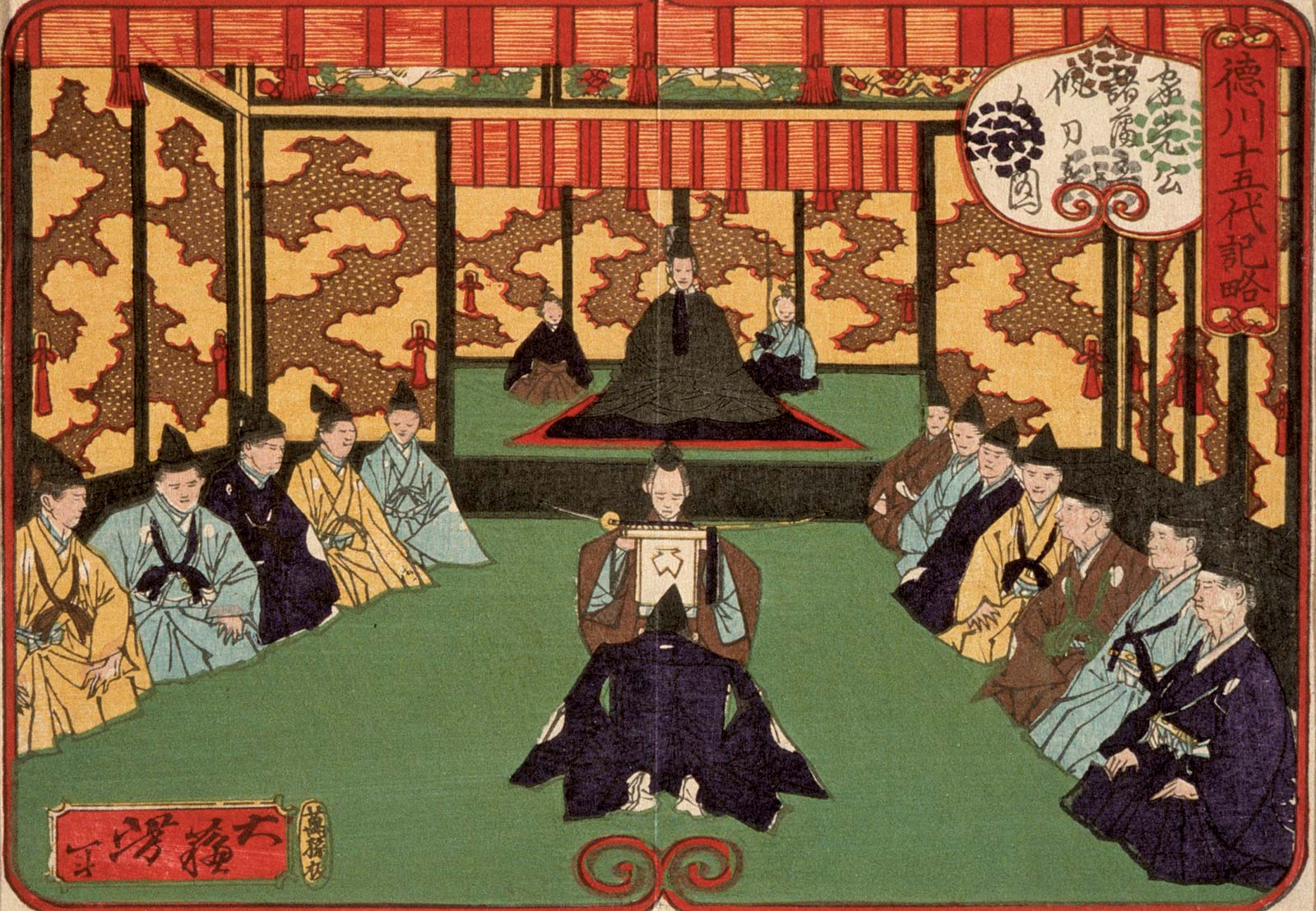

In 1600 a coalition of daimyo forces led by Tokugawa Ieyasu triumphed over an alliance of daimyo from western Japan. He gained an immense amount of territory allowing him to reward his loyal followers but at the same time dispose of all daimyo who would not accept his overlordship. In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu was invested by the Emperor with the position of Shogun - traditionally the highest military office in the land. Although the Emperor lacked real political power, he was regarded as the source of political legitimacy and the symbol of national unity and so this investiture was important for securing Ieyasu's position.

Ieyasu now swiftly consolidated power from his heavily fortified castle at Edo. He would go on to establish control over all Japan and to establish a new system of government which became known as the Tokugawa system.

2. How was society organised under the Tokugawa Shogunate?

The Tokugawa leaders set out to create institutions that would stabilize the political and social conditions of the country, thereby preventing a breakup of their coalition and a lapse back into feudal warfare. They succeeded remarkably well; the Tokugawa system endured until 1868;

Pyle, The Making of Modern Japan, D. C. Heath and Co, 1996, pg 29

From: MYP by Concept: History, by Jo Thomas and Keely Rogers

As the quote from Pyle above indicates, the Tokugawa now set out to impose an ordered structure on society in order to ensure political stability. However, rapid economic development over the next few generations would mean that the system would become 'marred by inconsistencies and contradictions'. (W. G. Beasley, The Japanese Experience, 1999, pg 152)

Task One

ATL: Self-management skills and thinking skills

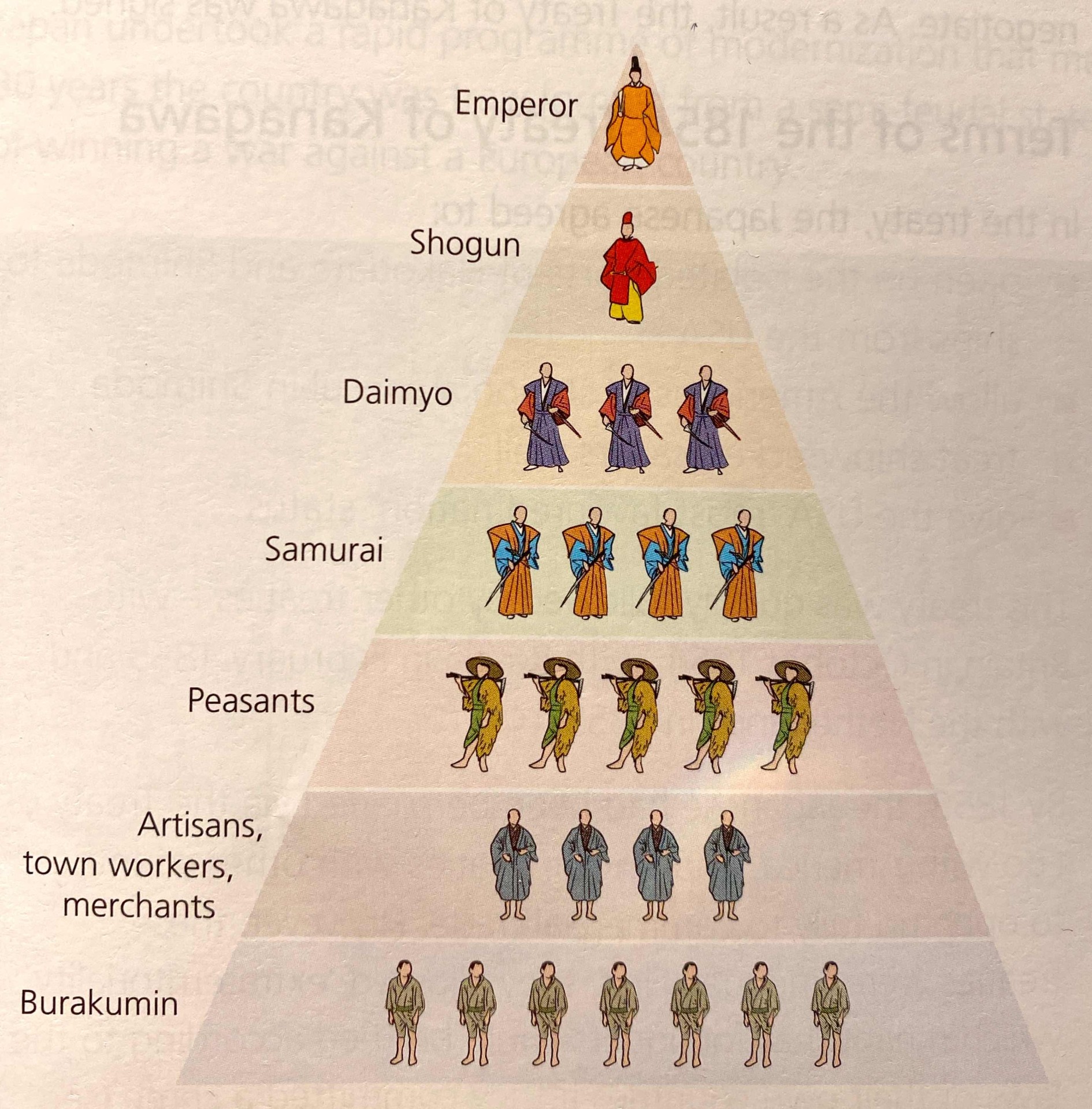

1. Copy out the diagram above showing the feudal system in Japan. Put it in the centre of an A3 sheet of paper.

2. Continue watching the video above.

3. Using the video, the information below, and any information from your own research, add details to your diagram about each social class

4. Discuss as a class any problems that you can see with the way that society and the economy developed under the Tokugawa. What evidence can you find to support Beasley's claim that the system became 'marred by inconsistencies and contradictions' ?

At the top of the political structure in Japan was the Emperor. However, he lacked political power and was treated like a prisoner of the Shogun, confined to his palace grounds. Real power lay with the Shogun. In theory the post of Shogun was both hereditary and autocratic but for the most part the real decisions of government were taken by those who held posts in the central administration which was known as the Bakufu.

Japan was divided into provinces [called han] and each of these was ruled by a feudal lord or daimyo who owed his position to the Shogun. The Shogun controlled the daimyo by making sure that they spent every other year living in his headquarters in Edo. When a daimyo returned home he had to leave his family behind as ‘hostage'. The daimyo also could not marry without the shogun's approval. The number of their vassals and the size of their castles were regulated by law and they were also forbidden to socialise with people outside of their own domain to prevent any plotting. The Shogun kept Japan isolated from the West partly to make sure that no daimyo ever made alliances with other countries or got weapons from other countries.

Below the daimyo in the feudal ‘pyramid of power’ came the samurai or warrior class. They had certain privileges e.g. the right to wear swords, and they had to live by a certain code of behaviour called ‘bushido’ [the way of the warrior] which stressed loyalty, bravery and honour. A Samurai who behaved dishonourably was expected to commit suicide publicly by the ritual of ‘seppuku’ [belly-cutting]. They were awarded a wage or stipend, and some samurai played an important part in the government of the daimyo, but others were very poor (see below). Indeed, as the country entered a period of peace in this period, the samurai transformed from being a feudal military class to a bureaucratic elite. They were also encouraged to pursue learning. As Pyle writes, 'at the beginning of the Tokugawa Period warriors were a rough, unlettered class, but by the end nearly all were literate and schooled'.

The majority of the population were peasants. They mainly cultivated rice. However, they were kept in poverty by the high feudal taxes which meant that the daimyo took between 40 – 60% of a peasant's household rice production every year. The lives of farmers were strictly controlled by law; they had to wear cotton clothes, not silk; a law specified the exact day they had to change from summer to winter garments and vice versa; they could not travel outside of their districts without special permission; they were often recruited to do highway work without pay which meant that they were forced to neglect their own fields.

Some peasants, however benefited from the changing economy in peace time. Commercial farming grew rapidly and widely during the Tokugawa Period as villages grew crops to fulfil the demands of the growing towns and cities. Regional specialisation in commercial crops steadily increased and small village enterprises such as sugar, salt, tea, oil spread rapidly so that some farmers now had extra jobs other than that of agriculture. The commercialisation of agriculture in turn encouraged the use of money. These developments saw the rise of wealthy peasants (gono) who benefited from this commercialisation. However, there were still landless peasants and the period saw a growing disparity of wealth and a sharp increase in the number of peasant uprisings. (see below)

The artisans and merchants were at the bottom of the pyramid of power, but their wealth meant that they were often more influential than those higher in the social order. They were growing in numbers and power and they wanted this power reflected by the position they held in society. Although ancient laws also supposedly controlled their lives, they started to become emancipated from these rules because the samurai and daimyo needed them for their money. The samurai, daimyo and even the Shogun borrowed money from them. Many merchants upgraded their status by paying money in order to become samurai. They were also adopted as sons by samurai who owed them money.

At the bottom of the feudal system were the ‘untouchables’ or ‘Eto’. These people did the 'dirty' jobs in society – digging and filling cesspits and burying the dead.

More on the control of these sections of society is covered on the video Japan - History of a Secret Empire - The Samurai, the Shogun, & the Barbarians from 1 hour 6 minutes. See the video page:

Historians have often questioned why the Tokugawa did not establish a unified, centralised state such as those that emerged in Europe at this time.

Task Two

ATL: Thinking skills

Why, according to Pyle, did the Tokugawa not choose to further consolidate and centralize their power?

Feudalism in Japan was not yet ready to disintegrate at this time.... The unifiers had been dependent on feudal alliances at every step along the way to consolidating national power. The Tokugawa shogunate lacked the independent military and administrative capacity to unite the country; it was dependent on the compliance of the daimyo. Each needed the other. For the daimyo, joining in this system provided a kind of collective security and legitimacy.

K Pyle, Modern Japan, pg 26

3. Why did the changes to society during the Tokugawa rule lead to discontent?

'The late Tokugawa Period was increasingly a world out of joint. it was pervaded by a sense of malaise, disarray, and failed expectations'

Pyle, Modern Japan, pg 49

The period of peace discussed above, and the growing economy, created strains in the economic and social system in the second half of the Tokugawa period.

Task One

ATL: Thinking skills

- Read the following source from historians Reischauer and Craig

- List the problems that they identify as existing in the late Tokugawa system. List these problems under political, economic, social, cultural headings.

The military effectiveness of the samurai had declined seriously, and their sense of personal loyalty to the shogun or daimyo had become more a loyalty to the system in which individual men were little more than symbols. There was a rising awareness of the supreme national symbol of the emperor and a growing demand for the recognition of individual talent in addition to hereditary status. The commercial economy and urban society and culture had expanded far beyond the narrow feudal confines of the early seventeenth century. The aggressive entrepreneurial spirit of urban merchants and rich peasants, with its strong overtones of an achievement - rather than status-oriented ethic, was not at all in line with the emphasis of the ruling class on an unchanging agrarian economy and society. There was a growing diversity of intellectual trends among all classes, including a rising interest in Western science.

Reischauer and Craig, Japan, pg 114 to 115.

Task Two

ATL: Thinking skills

As you read below, add other challenges faced by the Tokugawa Shogunate to the lists you wrote for Task One.

Economic problems

The social and political structure that is described above caused economic strains in the Tokugawa system:

- The costs of government grew rapidly. In addition, with the growth of cities, government became more complex; however at the same time there was a growth in laxity and corruption.

- The lifestyle of the daimyo was extravagant and the alternate attendance system was hugely expensive; they tended more and more to exceed their income, which was largely drawn from the land tax which accounted for a shrinking portion of the total economy.

- Meanwhile, there was a failure to develop adequate ways of taxing the growing sectors of the economy.

Social problems

Financial problems in the government mean that it was frequently unable to pay the stipends of the Samurai; this of course led to increasing unrest in society. By the end of the Tokugawa Period, the majority of Samurai were living in frugal circumstances - often less well off than the wealthy peasants (see below) or the merchants. This was humiliating to the Samurai and led to declining morale. In order to gain more money, some adopted merchant boys, or married into merchant family. Alternatively some sold their armour or set up small industries. Many younger samurai also felt frustration at being kept out of office. Traditionally appointments were made on the basis of social rank and so the most important offices went to the higher-ranking samurai. Thus younger Samurai felt cut off from positions of power and saw themselves more fit and able to rule than the upper-class warriors whose wealth and easy lives meant that they were more susceptible to corruption and incompetent rule.

Given this situation, the loyalty of the Samurai to their lords was severely strained. Historians argue that that their loyalty - a key aspect of their position and character - now shifted from the lord to the han itself; a kind of 'han nationalism' which would lay the foundations for modern nationalism.

Not all Samurai were impoverished, but all felt the injustice of being unable to live as well as other classes. Particularly acute was the resentment felt towards the wealthy peasants who, as discussed above, had taken on a variety of rural enterprises which had given them a comfortable lifestyle.

Indeed, one contemporary wrote of the rich peasants:

Now the most lamentable abuse of the present day among the peasants is that those who have become wealthy forget their status and live luxuriously like city aristocrats... They build [homes] with the most handsome and wonderful gates, beams, alcoves, ornamental shelves, and libraries... They themselves wear fine clothes and imitate the ceremonial style of warriors on all such occasions as weddings, celebrations, and masses for the dead'.

Meanwhile, other peasants lived at subsistence levels and thus suffered in times of bad harvests. Famines on a national level occurred in the 1720s, 1780s and the 1830s and outbreaks of peasant rebellions took place as a result.

A 'cultural crisis'

The economic and social unhappiness described above also came to be reflected in looking for new concepts intellectually and spiritually. Pyle refers to a 'cultural crisis' in the last decades of Tokugawa rule.

National learning or nativism (kokugaku) began in the 18th century as a literary movement. The idea was to look at Japan's ancient classics to study Japanese life before the onset of China's cultural influence. This meant going back to the times of the worship of the Shinto Gods - and their descendant, the Emperor. Clearly, for those who saw this as the 'authentic' spirit of tradition of Japan, it tended to enhance the role the Emperor should play. The ideas of kokugawa spread to the countryside and were popular with wealthier peasants.

The Mito school of learning was another intellectual feature of the late Tokugawa period. The Mito school was devoted to the study of Japanese history, emphasising reverence for the Emperor.

Task Three

ATL: Thinking and communication skills

As you read above, Ieyasu chose Edo (present-day Tokyo) as Japan's new capital, and it became one of the largest cities of its time and was the site of a thriving urban culture.

In groups, research further the culture of Edo Japan. You could take one of the following each and produce a presentation for the rest of the class:

- Banruku and Kabuki theatre

- the role of women in society

- Woodblock images

- Printing and publishing

- Literature and poetry

- Intellectual trends

Task Four

ATL: Thinking and communication skills

Work in groups to create a documentary on Tokugawa Japan in the early 19th Century with the aim of highlighting the strains existing in society.

Students should take the roles of the Shogun, a daimyo, a samurai, a rich farmer, a poor farmer and a merchant, with one student being the interviewer and 'anchor'.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team