3. Liberation Theology in Latin America

This page examines Liberation Theology, a radical movement that developed in Latin America as a response to the poverty and the ill-treatment of ordinary people; it looks at the causes of the movement, the opposition that it faced and its lasting impact.

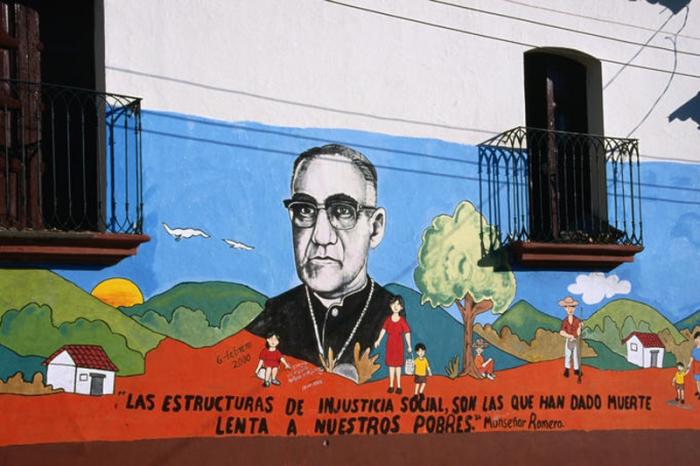

Mural of St. Oscar Romereo

http://www.latinolife.co.uk/node/214

Guiding questions:

When and why did Liberation theology emerge?

Why did the growth of Liberation Theology lead to criticism?

What were the main features of Liberation Theology?

What was the impact of Liberal Theology in Latin America?

Starter:

Read the source below.

- What, according to St Oscar Romero, is the role of the Church in El Salvador?

- To what extent were the political and economic conditions which St Oscar Romero refers to here present in other Latin American countries?

When we struggle for human rights, for freedom, for dignity, when we feel that it is a ministry of the church to concern itself for those who are hungry, for those who have no schools, for those who are deprived, we are not departing from God's promise. He comes to free us from sin, and the church knows that sin's consequences are all such injustices and abuses. The church knows it is saving the world when it undertakes to speak also of such things.

A church that doesn't provoke any crises, a gospel that doesn't unsettle, a word of God that doesn't get under anyone’s skin, a word of God that doesn't touch the real sin of the society in which it is being proclaimed — what gospel is that?

St Oscar Romero, Archbishop of El Salvador, assassinated in 1980

1. When and why did Liberation theology emerge?

The CELAM meeting in 1968 in Medellin, Columbia

Q: How are we to be Christians in a world of destitution and injustice?

A: There can be only one answer: we can be followers of Jesus and true Christians only by making common cause with the poor and working out the gospel of liberation.

Leonardo and Clodovis Boff

For centuries, the Church in Latin America was the bulwark of conservatism, associated with the Conquest and colonial order first and to the new elites after independence.

Liberation theology encouraged a break from an elitist notion of the Church and the return of control to the people. By involving the poor in their own liberation and offering Christianity as a tool towards a more perfect society, liberation theologians dramatically changed the relationship between not only the Church and the state, but also the Church and the people.

Guided by the innovative Peruvian priest, Gustavo Gutiérrez, this movement reinvigorated marginalized people in Peru and throughout Latin America, while still utilizing a formal theological approach.

At its height in the late 1960s and 1970s, liberation theology preached that it was not enough for the church to simply empathise and care for the poor. Instead, believers argued, the church needed to be a vehicle to push for fundamental political and structural changes that would eradicate poverty, even – some believed – if it meant supporting armed struggle against oppressors.

Moved by the Cuban Revolution of 1959 and the increasing pressure for similar change, progressive clergy members began meeting to discuss the future of the Church and its role in the politics of society.

CELAM or the Latin American Episcopal Conference worked to push the Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican or Vatican II, a series of meetings from 1962 through 1965 that focused on Church unity and renewal, towards a more progressive stance. Vatican II represented an international conference where high-level Catholic religious figures rethought Church policy and discussed processes of modernization.

Task One

ATL: Thinking skills

In pairs read through the following extracts from Gaudium et Spes, On the Church in the Modern World, December 1965 (Vatican II Online Documents) and discuss with a partner the questions that follow:

- According to the Church, what kind of renewal must take place in the Modern World?

- How could the role of Christians be interpreted in the light of the political and economic turmoil of Latin America in the 1960s?

In many underdeveloped regions there are large or even extensive rural estates which are only slightly cultivated or lie completely idle for the sake of profit, while the majority of the people either are without land or have only very small fields, and, on the other hand, it is evidently urgent to increase the productivity of the fields. Not infrequently those who are hired to work for the landowners or who till a portion of the land as tenants receive a wage or income unworthy of a human being, lack decent housing and are exploited by middlemen. Deprived of all security, they live under such personal servitude that almost every opportunity of acting on their own initiative and responsibility is denied to them and all advancement in human culture and all sharing in social and political life is forbidden to them. According to the different cases, therefore, reforms are necessary: that income may grow, working conditions should be improved, security in employment increased, and an incentive to working on one's own initiative given. Indeed, insufficiently cultivated estates should be distributed to those who can make these lands fruitful; in this case, the necessary things and means, especially educational aids and the right facilities for cooperative organization, must be supplied. Whenever, nevertheless, the common good requires expropriation, compensation must be reckoned in equity after all the circumstances have been weighted. (...)

The Church, by reason of her role and competence, is not identified in any way with the political community nor bound to any political system. She is at once a sign and a safeguard of the transcendent character of the human person. The Church and the political community in their own fields are autonomous and independent from each other. Yet both, under different titles, are devoted to the personal and social vocation of the same men. The more that both foster sounder cooperation between themselves with due consideration for the circumstances of time and place, the more effective will their service be exercised for the good of all. For man's horizons are not limited only to the temporal order; while living in the context of human history, he preserves intact his eternal vocation. The Church, for her part, founded on the love of the Redeemer, contributes toward the reign of justice and charity within the borders of a nation and between nations. By preaching the truths of the Gospel, and bringing to bear on all fields of human endeavor the light of her doctrine and of a Christian witness, she respects and fosters the political freedom and responsibility of citizens.

In 1968, CELAM organized a meeting in Medellin, Colombia, with the hope of supporting base ecclesiastic communities and the continued reformation of the Church. It was at this conference that Gustavo Gutiérrez first presented the term “liberation theology” in a paper called “Toward a Theology of Liberation”.

The concepts referenced during this talk in 1968 were more clearly laid out in his 1971 magnum opus, “A Theology of Liberation.” In an atmosphere of increasing clerical reform, liberation theology emerged as a new way of “being human and Christian”.

2. What were the main features of Liberation Theology?

Gustavo Gutiérrez, a Peruvian philosopher, theologian, and Dominican priest who is regarded as one of the founders of liberation theology

Task One

ATL: Thinking and Communication skills

You are a journalist for a well know radio program. Watch the following interview with Gustavo Gutiérrez from 3 minutes 17 seconds to the end.

Prepare a set of questions you would ask him in order to find out more about his religious vision of poverty and the preference for the poor in Liberation Theology.

Task Two

ATL: Thinking skills

Watch the first four minutes of the following video.

How did Liberation Theology affect the actual conduct of church services?

Why was Liberation Theology so controversial in the context of Nicaragua in the 1980s?

Task Three

ATL: Thinking and communication skills

In small groups read through the information below and create an infographic outlining the key features of Liberation Theology.

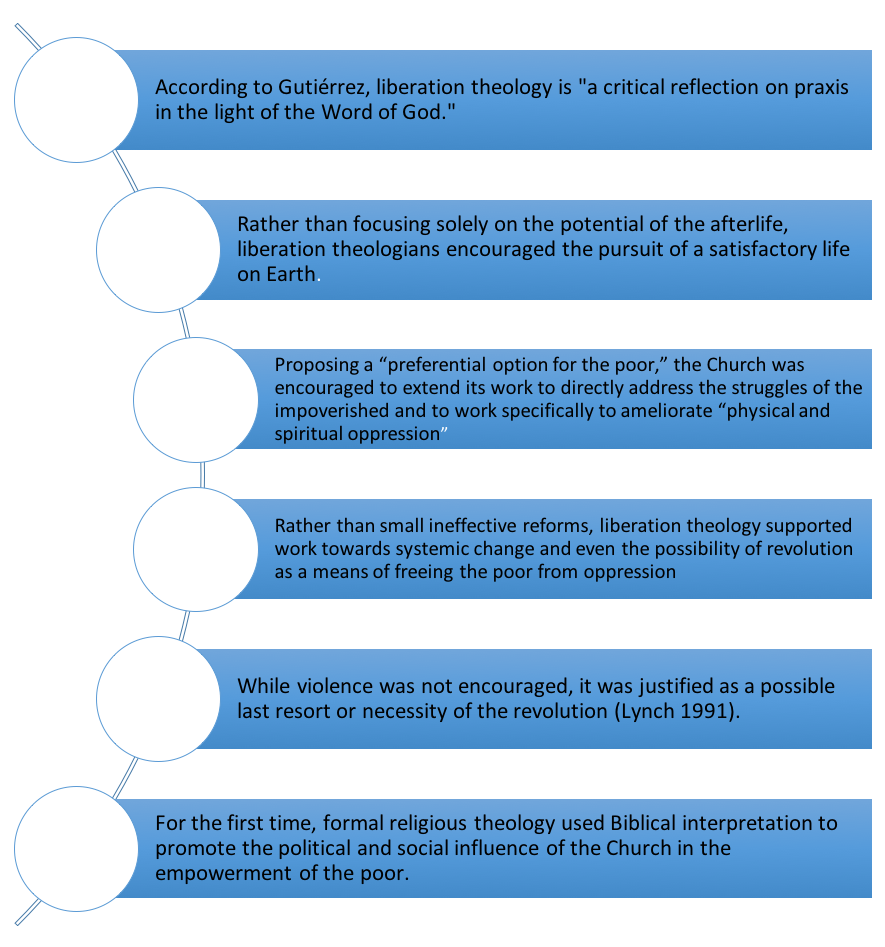

Liberation theology looks to understand Christianity and religion through the salvific process of liberation. Such a theology does “not stop with reflecting on the world, but rather tries to be a part of the process through which the world is transformed” (Gutiérrez 1973, 12).

People are encouraged to become active agents of their own destiny and in effect to liberate themselves from the confines of injustice.

Therefore, the church in Latin America should be actively engaged in improving the lives of the poor. In order to build this church, comunidades de base, (“base communities”) were established which were local Christian groups, composed of 10 to 30 members. These groups both studied the Bible and attempted to meet their parishioners’ immediate needs for food, water, sewage disposal, and electricity

This theology extended to suggest that there were three distinct levels of real freedom or liberation, representing the aspirations of oppressed peoples, a means to look at history and a new approach to Biblical interpretation (Gutiérrez 1973).

- At the first level, the poor were to liberate themselves from economic exploitation. Overcoming poverty became a fundamental tenant of liberation theology.

- At the second level, the hope was liberation from fatalism, the recognition of free will.

- Lastly, at the theological level, liberation from sin would result in ultimate liberation and communion with God.

Task Four

ATL: Thinking skills

In pairs look at the chart below and discuss the implication of Liberation Theology in practice.

Task Five

ATL: Thinking skills

In pairs, read the following extract written by Gustavo Gutierrez in his book The Power of the Poor in History (1983) . With reference to its origin, purpose and content analyse its value and limitations for a historian seeking to understand the main features of Liberation Theology.

If I define my neighbor as the one I must go out and look for, on the highways and byways, in the factories and slums, on the farms and in the mines –then my world changes. This is what is happening with the “option for the poor”, for in the gospel it is the poor person who is the neighbor par excellence….

But the poor person does not exist as an inescapable fact of destiny. His or her existence is not politically neutral, and is not ethically innocent. The poor are a by-product of the system in which we live, and for which we are responsible. They are marginalized by our social and cultural world. They are the oppressed, exploited proletariat, robbed of the fruit of their labour and despoiled of their humanity. Hence the poverty of the poor is not a call to generous relief action, but a demand that we go and build a different social order.

3. What criticisms developed against Liberation Theology?

Pope John Paul II who was a critic of Liberal Theology

Starter:

What criticism of Liberation Theology is being made in this statement by Cardinal Ratzinger:

Faced with the urgency of certain problems, some are tempted to emphasize, unilaterally, the liberation from servitude of an earthly and temporal kind. They do so in such a way that they seem to put liberation from sin in second place, and so fail to give it the primary importance it is due.'

The Liberation Theology movement gained strength in Latin America during the 1970s. However, because of their insistence that ministry should include involvement in the political struggle of the poor against wealthy elites, liberation theologians were often criticized—both formally, from within the Roman Catholic Church, and informally—as naive purveyors of Marxism and advocates of leftist social activism. By the 1990s the Vatican, under Pope John Paul II had begun to curb the movement's influence in Latin America by appointing conservative priests and bishops.

Task One

ATL: Thinking skills

Read the following which comes from a sermon by the Pope in Mexico, 1990, 'Option for the Poor'.

What criticisms does the Pope make of Liberation Theology?

...When the world begins to notice the clear failures of certain ideologies and systems, it seems all the more incomprehensible that certain sons of the Church in these lands - prompted at times by the desire to find quick solutions - persist in presenting as viable certain models whose failure is patent in other places in the world.

You, as priests, cannot be involved in activities which belong to the lay faithful, while through your service to the Church community you are called to cooperate with them by helping them study Church teachings...

...Be careful, then, not to accept nor allow a Vision of human life as conflict nor ideologies which propose class hatred and violence to be instilled in you; this includes those which try to hide under theological writings.

Pope John Paul II's main aim was to stop the highly politicised form of liberation theology prevalent in the 1980s, which could be seen as a fusion of Christianity and Marxism. However he was frequently criticised for the severity with which he dealt with the liberation movement. He was particularly criticised for the firmness with which he closed institutions that taught Liberation Theology and his actions in removing or rebuking the movement's activists, such as Leonardo Boff and Gustavo Gutierrez.

He believed that to turn the church into a secular political institution and to see salvation solely as the achievement of social justice was to rob faith in Jesus of his power to transform every life. The image of Jesus as a political revolutionary was inconsistent with the Bible and the Church's teachings.

He did not mean that the Church was not going to be the voice of the oppressed or was not to champion the poor. But he believed that the Church should not do it by partisan politics, or by revolutionary violence. The Church's business was to bring about the Kingdom of God. Social action should be in the image of the Gospel and the Gospel was open to everyone:

Jesus makes it a condition for our participating in his salvation to give food to the hungry, give drink to the thirsty, clothe the naked, console the sorrowing, because "when you do this to one of my least brothers or sisters you do it to me" (Mt 25:40).

Pope John Paul II

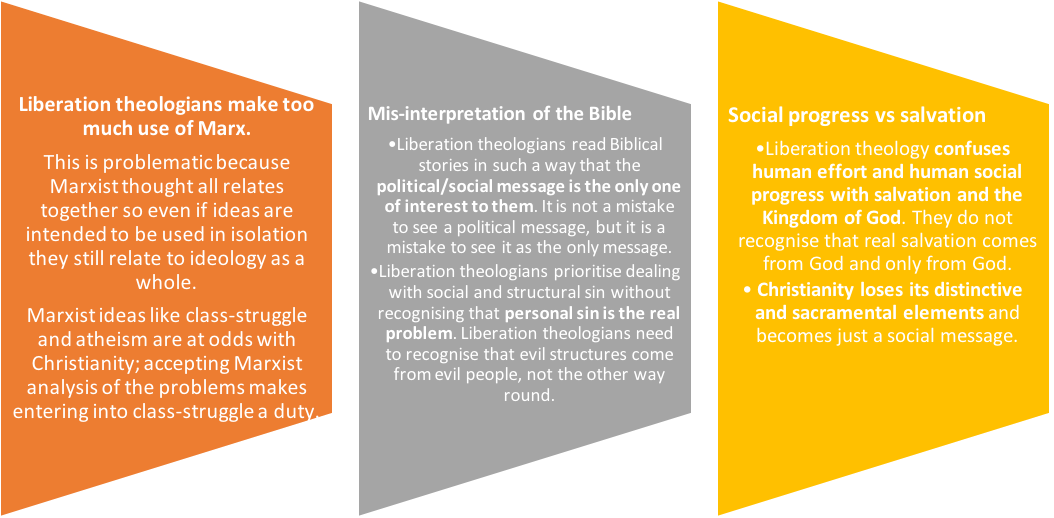

Another critic of Liberal Theology was Cardinal Ratzinger. His key objection to the content of liberation theology was that liberation theologians misrepresent the Biblical message and misunderstand key Christian ideas. This occurs because they interpret the Bible in the light of experience and making use of Marxist ideas and terminology.

In The Libertatis Nuntius or 'Instruction on certain aspects of the "Theology of Liberation"' in 1984, Cardinal Ratzinger identified several problems with Liberation Theology:

It is important to note that Ratzinger stressed that Christians should be concerned with social justice, that they should try to change society and that they should pay attention to the social message of the Gospel. He said that the 'scandal of the shocking inequality between the rich and poor' should not be tolerated.

He also cautioned that his criticism of Liberation Theology 'must not be taken as some kind of approval, even indirect, of those who keep the poor in misery, who profit from that misery, who notice it while doing nothing about it, or who remain indifferent to it. The Church, guided by the Gospel of mercy and by the love for mankind, hears the cry for justice and intends to respond to it with all her might.'

To sum up, the dispute is not about whether the poor should be helped but HOW they should be helped.

Task Two

ATL: Thinking and communication skills

You and a partner have been commissioned by Pope John Paul II’s office to write a letter explaining to the people of your town or village why the Church is opposed to the Liberation Theology.

Provide some arguments and link them to specific evidence.

What was the impact of Liberation Theology in Latin America?

Task One

ATL: Thinking skills

Read this article; scroll down to the heading 'Ultimate decline and lasting impact of Liberation Theology'

Make notes on

a. reasons why the movement declined.

b. its lasting impact

According to Political Science Professor Daniel H Levine, the new discourse about justice and equality rooted in biblical and religious themes is now widespread and will probably remain. Probably the most critical long- lasting impact of Liberation Theology are the Base Communities which embody the transformative power of grass-root initiatives. Yet Professor S. Mainwaring has pointed out that in Brazil, concerns about protecting the popular authenticity of Liberation theology have narrowed and restricted its focus, as they refuse to look beyond the grass-roots level. This endangers the possibilities of transcending local boundaries and building other networks that could bring further visibility to their communities.

Professor Edward Lynch points out that the most convincing proof of liberation theology's retreat, is the speed with which liberation theology is changing. Liberationists acknowledge new directions and new emphases in their work, but insist that these seeming changes were present from the beginning. Lynch argues that this is not the case. He points out that most observers have noted radical changes in the movement in the last few years. The movement is demonstrating much more skepticism of Marxism and of dependency theory.

Professor Levine notes that liberation theology is redirecting its "central concerns away from politics in the narrow sense to issues of popular religion, spirituality, and long-term social and cultural change". In other words, liberationists are now centrally concerned with certain aspects that liberation theology used to ignore.

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team