1. Soviet motives for taking control in central and eastern Europe 1945 - 1955

Central and eastern European states faced political and economic challenges in the interwar years and were vulnerable to Soviet influence following the Second World War. This vulnerability was exploited by Stalin who established Soviet dominated communist parties in the countries 'liberated' by the Red Army after 1943. This page examines Stalin's motives for wanting to secure such firm control in central and eastern Europe.

Guiding questions:

What was the situation regarding central and eastern Europe before 1945?

What motivated the Soviets to dominate central and eastern Europe?

What motivated the Soviets in each of the central and eastern European states?

1. What was the situation regarding central and eastern Europe before 1945?

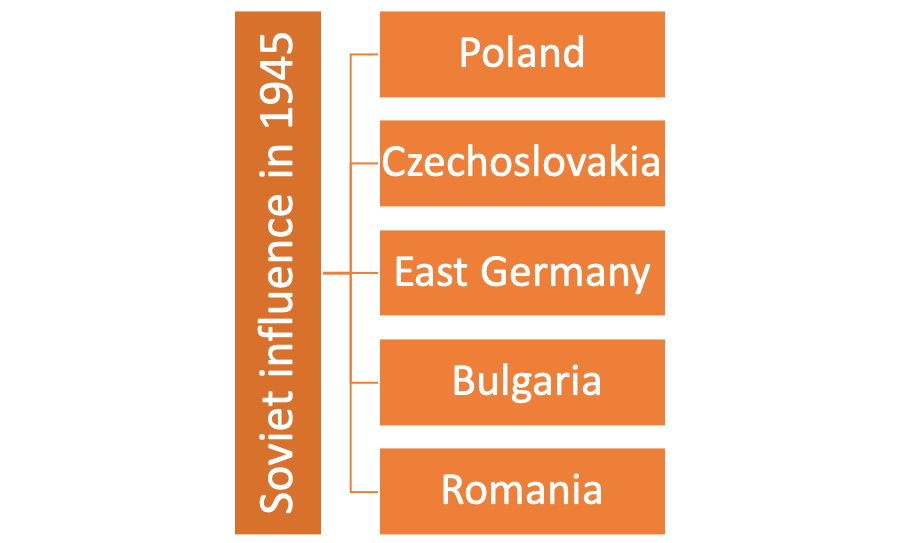

The states that we will be focusing on in this unit are Poland, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia and Romania. For centuries most of these states had been part of the multinational Habsburg, Russian and Ottoman empires and they were less urbanised and industrialised than western European states.

After the First World War and the collapse of these empires, national boundaries in Europe were redrawn. In the Versailles Settlement, Germany and Austria ceded territory and ‘Anschluss’ was forbidden. One of the war aims of the Allied powers had been to pursue ‘self-determination’ for national groups. Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania had their independence confirmed at the end of the war. Poland regained independence for the first time since its partition in the 18th century. Czechoslovakia, and the kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes – called Yugoslavia from 1929 - became newly independent states. After the Bolshevik revolution in Russia and the subsequent civil war, Ukraine and Belarus were taken under Soviet control but the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania declared independence. Finland proclaimed itself a republic in 1919.

The newly independent states, or ‘successor states’ were vulnerable, economically and politically, to influence from both the Soviet Union and a resurgent Germany. Economically, most states, bar Hungary, redistributed the land from the aristocratic estates to the peasantry after the First World War. However, the majority of people remained subsistence farmers. Subsequently, as a result of population growth coupled with the global depression of the 1930s, there were acute economic pressures on these states. Territorial disputes and claims also led to instability in the region; however these tensions were exacerbated by the rather arbitrary drawing up of the borders of Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia which had taken place after the First World War and which disregarded ethnic distributions. There were no guarantees for the safety of minorities in these new states, for example the German speakers in Czechoslovakia, and there was no history of democracy in these states. Indeed, in the inter-war period only Czechoslovakia remained a democracy before the outbreak of the Second World War.

Task One

ATL: Thinking skills

In pairs look at the map above and review the terms of each of the treaties of the Versailles Settlement.

Discuss the potential challenges that the newly independent states of central and eastern Europe might face after the First World War.

Get into groups of six. Each student will research one of the following ‘successor’ states:

- Czechoslovakia

- Yugoslavia

- Poland

- Romania

- Hungary

- Bulgaria

You need to develop a brief ‘guide to’ your successor state in the inter-war period, from its establishment after the First World War through to the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. You must include information and details on the following:

- Political nature of the state [e.g. democracy, military dictatorship etc]

- Economic situation [including the key strengths, limitations, evidence of stability and growth and evidence of issues]

- Social developments [this could include, education, the arts, the role of women in society, the role of religion in society etc]

- Foreign policy [this could include aims, fears, treaties, alliances and other developments]

Present your findings to your group.

3. As a group discuss the following questions:

- Which states seemed to be the most successful politically, economically and socially in the inter-war period?

- What were the main ‘aims’ and ‘fears’ of the successor states?

- Which states pursued an ‘aggressive’ or ‘expansionist’ foreign policy?

- To what extent were the successor states ‘stable and viable’ countries in the long term?

After Hitler came to power and began to rearm Germany, the surrounding countries of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Romania sought security in alliances with France. But Hungary moved to ally with Nazi Germany. In September 1938 the Czech Crisis led to the Munich Agreement in which British Prime Minister ceded Czech territory to Hitler’s Germany. This agreement was torn up by Hitler in March 1939 when he invaded and occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia. Then, in September 1939, following the Nazi-Soviet Pact in August, Poland was divided between Germany and the Soviet Union. This pact also gave Stalin free rein to seize control of the Baltic states - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. Hungary, Bulgaria and Romania allied with Hitler when he launched Operation Barbarossa in June 1941 – the invasion of the USSR.

Task Two

ATL: Research and communication skills

By September 1942 the Axis powers had occupied the territories in red on the map. Central and eastern Europe was under Nazi control.

In small groups research the nature and impact of the German occupation on the central and eastern European states: Poland, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Bulgaria and Romania. (Your group should not research Yugoslavia as we cover this at the end of the unit) .

Make sure you identify forces and groups that resisted and fought the Germans and those that collaborated and/or fought against the USSR.

During the war the Allies - the US, Britain and the USSR - met three times, at Tehran in 1943, at Yalta February 1945 and Potsdam July 1945. At each of the meetings the fate of central and eastern Europe after the Second World War was discussed and agreements made.

Task Three

ATL: Thinking skills

In pairs read through the chart below and discuss what was agreed between the Allies regarding the states of central and eastern Europe.

Identify where there seemed to be issues or conflict between the Allies on these proposed arrangements. To what extent had the Soviets begun to establish control over central and eastern Europe by the time of the Potsdam meeting?

2. What motivated the Soviets to dominate central and eastern Europe?

Cartoon by the British cartoonist Illingworth, June 1947

Starter:

What is the message of this cartoon?

'Stalin's postwar goals were security for himself, his regime, his country, and his ideology, in precisely that order'

John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War, pg 11

The motive for Soviet domination could be seen as ideological. Orthodox Western historians writing on the origins of the Cold War argued that expansionism was inherent in its Marxist ideology. Marxism advocated spreading revolution and the need to ‘liberate’ the exploited workers of the world.

Marxism–Leninism gave the Russian leaders a view of the world in which the existence of any non-Communist state was by definition a threat to the Soviet Union ... An analysis of the origins of the Cold War which leaves out these factors – the intransigence of Leninist ideology, the sinister dynamics of a totalitarian society and the madness of Stalin – is obviously incomplete. Arthur M Schlesinger, Jr, ‘Origins of the Cold War’, Foreign Affairs (October 1967) pp.49–50

However, it could also be argued that the motive was fear and insecurity. The Soviet leadership believed that the capitalist West sought to ‘encircle’ the Soviet Union and ultimately overthrow its communist government. Indeed, the economic effects of the Second World War were severe for the USSR whereas the US emerged from the conflict as the number one global economic power. The Soviets were concerned that the US would use its economic power to gain influence in other countries.

The US set up the Bretton Woods system at the end of the war, which included the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Although involved in setting these institutions up, the USSR withdrew in 1945 due to the emphasis on free market capitalism. Together with the US Marshall Plan, proposed in 1947 and implemented in 1948, the Soviets viewed US policies as the pursuit of ‘dollar imperialism’ and they were afraid that the USA was trying to win over the East European states with economic aid. In other words, the US would use its economic power to establish spheres of influence to promote its own economic and ideological power.

The Soviet Foreign Minister Sergei Molotov wrote a book, Problems of Foreign Policy, in which he accused the US of trying to take over Europe economically and put it under the control ‘of foreign firms, banks and industrial companies’. Molotov said the Soviets were only attempting to ‘find security’, to rebuild after the ‘Great Patriotic War’ (World War Two) and, where and when possible, to aid in the liberation of the exploited working classes of the world. In response the USSR set up COMECON which we will cover later on in this topic.

After the opening of former Soviet and Eastern European archives in the 1990s, historians have reconsidered the role of ideology and the search for security in Soviet foreign policy. Historians suggested that motives such as furthering socialist objectives became tied to the search for security. There was a belief in the USSR that the triumph of socialism was inevitable, and it should assist communist groups around the world to fulfil this aim. From the Soviet archives a clear motive seems to be the fear of renewed German aggression and aggression from the capitalist world.

Historians such as John Lewis Gaddis have also highlighted the paranoia that underpinned Stalin’s state and argue it was not surprising that Stalin viewed the actions of the West as a threat. Vojtech Mastny sees Stalin’s role as pivotal in the expansion of Soviet control and that paranoia and suspicion were the dominant motives.

However, US Secretary of State in the 1970s, Henry Kissinger, claimed that the USSR’s motives for the domination of central and eastern Europe were not based on the promotion of its ideology, nor due to security concerns but were rather motivated by traditional aims of empire building.

Task One

ATL: Thinking and communication skills

Copy out annotate this diagram to show how each of the factors shown in the chart may have motivated the Soviet Union to dominate central and eastern Europe. Identify and add an historian or an expert contemporary figure who supports each of these motives.

3. What motivated the Soviets in each of the central and eastern European states?

Before 1947, although the Red army remained in eastern Europe, the USSR did not exert overt force to expand its control, for example the Soviets did not assist a communist insurgency in Greece. Stalin did indeed set out to destroy pro-German elites in the territories formerly under occupation by the Nazis but it was not simply a case of the Red Army using its military presence and intimidation to exert influence. Communist forces had some popular support as it was these groups that had pushed for radical reform in the pre-war period and it was often communists who had led the resistance to the Germans during the war. At the end of the war communist groups were strengthened by the Soviet advance and the knowledge that they would have assistance.

There were several states that had governments in exile in Britain, but these governments were not necessarily popular in the post-war period at home. They were also not likely to be ‘acceptable’ to the Soviets. As the Cold War superpower confrontation developed, the USSR pushed for more political control over the communist parties in central and eastern Europe. Coalition governments of socialists, communists, democrats and peasant parties were initially formed and were dubbed ‘People’s Democracies'. These groups wanted to remove all remnants of fascism and wanted to implement land reform. Communists were given influential positions e.g. interior ministers, security chiefs and propaganda heads. Other political parties were slowly removed [see later ‘salami tactics’].

1. Poland

.png)

Map showing the new borders of Poland after the Second World War

From The Cold War, Rogers and Thomas, Pearson

A key motive for the Soviets to gain control over Poland was its historic use as the launchpad for invasions into Russia. It was deemed a key strategic territory for the USSR. Poland was vulnerable due to its geography, positioned between Germany and the USSR. The ‘carve up’ of Poland in 1939, in line with the Nazi-Soviet pact, meant that the Poles were not likely to support Soviet influence in their country. Poland had suffered the most per capita losses during the war with over 6 million dead. The USSR did not trust the Polish communist party and had had it eliminated in 1941. It was allowed to re-form in 1942 and join in a popular front with other resistance parties. Stalin supported an alternative Polish communist government in Moscow over the ‘London Poles’ government in exile in Britain to head a post-war government.

Task One

ATL: Thinking and research skills

Read the documents on this website page regarding British and American responses to the actions of the Red Army in not helping the Warsaw uprising in Poland as it advanced through Europe towards Germany.

(Please note that there is an error in the years for the sources 4 and 5 on the linked website page; the year should be 1944 not 1994!)

1. What can you learn form these exchanges about

a. the attitude of the Soviet Union towards the situation in Poland

b. the attitude of the British government towards the situation in Poland

c. the attitude of Roosevelt

2. What hints are there that this event could impact on relations between America, Britain and the Soviet Union after the end of the war?

3. What reasons could the Soviets have had for not helping the Polish underground resistance?

4. Also research the Katyn Forest Massacre which was uncovered in 1943. What were the reasons for the Soviets carrying out this massacre?

5. Review the chart above on the different war time conferences: what tensions were revealed concerning Poland at these conferences?

Wladslaw Gomulka, deputy leader of the Polish communist party, was ordered to negotiate with the London Poles in 1943. As you will have seen, the allies agreed to shift the border of Poland westwards during the wartime conferences. The proposal had caused great disagreement amongst the Polish. The Soviets sent Boleslaw Bierut (photo to the left) to work with Gomulka, but discussions broke down as Bierut refused to work with ‘socialists’. In February, 1944 the Red Army began to liberate Poland from Nazi occupation. The Polish committee for national liberation, established in Lublin under the leadership of Bierut was to have political control with Soviet support. Infighting in Poland ensued between the home army who supported the London poles and communists groups who supported the Lublin.

In January 1945 Stalin formally recognized Bierut’s committee as the provisional government of Poland and the Polish home army was disbanded; its leaders were sent to Moscow and imprisoned. A brutal but small scale civil conflict developed between communists and anti-communists in Poland. The US and Britain refused to recognize the new government until the free elections promised by Stalin at Yalta had been held.

Nevertheless, the Provisional Government of National Unity was established in June 1945 made up of communist, socialist, catholic and peasant parties. Edward Osobka was prime minister and former leader of the government in exile, Stanislaw Mikolajczyk of the peasant party, joined. The Western allies recognized the government and the border agreement was implemented.

2. Hungary

Security and opportunity were key motives for the Soviets to dominate Hungary. In addition, Hungary had joined the Germans in Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the USSR, and therefore had been an enemy state. Despite the alliance, Hitler had not trusted the Hungarians and the Nazis had actually occupied Hungary in 1944. The small Hungarian communist party had been illegal before the war, and during the war the socialist-peasant party was suppressed. Communists led by Laslo Rajk joined with the socialists in a popular front against the ‘fascists’ and after the Red Army invaded Hungary in June 1944, the Hungarian communists attempted to have influence. A National Independence Front was set up and Stalin ordered the communists to join a coalition government. The USSR did not want the Hungarians to wield too much independence. Matyas Rakosi (see photo on left) was put in charge of rebuilding the communist party in line with Moscow’s orders.

Czechoslavakia

Czechoslovakia was a country that would come to be on the frontline between the western and eastern blocs in Europe. Before the Second World War the Czech communists were fairly established in Czechoslovakia, unlike in Hungary and Poland. The Soviets perceived the state as key to security, but also wanted to harness its economic potential. The unification of the lands of Czechs and Slovaks at the end of the First World War led to some nationalist and socio-economic tension. The Czechs were more urbanized whereas 80% of Slovaks were poor peasants. Nevertheless, Czechoslovakia was the real success story of multinational democracy in the inter-war period. The Communist party had some popularity and had won 10% of the vote in national elections. During the war, Czechoslovakia had a government in exile in London led by President Eduard Beneš. Back home, Klement Gottwald (see photo on the left) led the communists in resisting the Nazi occupation. Stalin signed an agreement with the Beneš government in 1943 in which it was agreed that pre-war borders would be respected. In August 1944, a Slovak national rising was organized from London, but this had a limited impact as the communists had gained significant influence, and had the back-up of the Red Army when the Soviets invaded in October 1944.

Czechoslovakia was a country that would come to be on the frontline between the western and eastern blocs in Europe. Before the Second World War the Czech communists were fairly established in Czechoslovakia, unlike in Hungary and Poland. The Soviets perceived the state as key to security, but also wanted to harness its economic potential. The unification of the lands of Czechs and Slovaks at the end of the First World War led to some nationalist and socio-economic tension. The Czechs were more urbanized whereas 80% of Slovaks were poor peasants. Nevertheless, Czechoslovakia was the real success story of multinational democracy in the inter-war period. The Communist party had some popularity and had won 10% of the vote in national elections. During the war, Czechoslovakia had a government in exile in London led by President Eduard Beneš. Back home, Klement Gottwald (see photo on the left) led the communists in resisting the Nazi occupation. Stalin signed an agreement with the Beneš government in 1943 in which it was agreed that pre-war borders would be respected. In August 1944, a Slovak national rising was organized from London, but this had a limited impact as the communists had gained significant influence, and had the back-up of the Red Army when the Soviets invaded in October 1944.

Romania

Romania, on the Black Sea, was another strategically important state for the USSR; it bordered the Ukraine, Hungary and Yugoslavia. There was also the issue of ‘revenge’ as Romania had joined the Germans in the attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. Before the Second World War there were German, Jewish and Hungarian minorities in the country. It was economically less developed than other states in the region and had relied on Germany for economic support and for its defence. In 1940 Romania was forced to cede the territories of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the USSR and northern Transylvania to Hungary.

Romania, on the Black Sea, was another strategically important state for the USSR; it bordered the Ukraine, Hungary and Yugoslavia. There was also the issue of ‘revenge’ as Romania had joined the Germans in the attack on the Soviet Union in 1941. Before the Second World War there were German, Jewish and Hungarian minorities in the country. It was economically less developed than other states in the region and had relied on Germany for economic support and for its defence. In 1940 Romania was forced to cede the territories of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the USSR and northern Transylvania to Hungary.

From 1943, Romanian communists attempted to form an anti-Nazi coalition, and Stalin made Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej head of communist party in 1944 and instructed him to pursue this alliance. Subsequently, the National Democratic Front was formed in June 1944 which was a coalition of communists, socialists, peasant party members and liberals. The Romanian government then switched sides in the war to support the Allies. The Red Army entered Bucharest in August 1944, and in September Churchill agreed to Stalin’s demand for ‘primary influence’ in Romania (see Percentages Agreement in table above). The first communist-dominated government came to power in March 1945 under the leadership of Petru Groza (see photo).

Bulgaria

Bulgaria was deemed important for Soviet security, and had been an ally of the Germans and thus an ‘enemy’ state. Nazi Germany had urged Bulgaria to join the Tripartite Pact powers after Italy’s invasion of Greece had failed. Hitler wanted to be able to send his forces through Bulgaria into Greece to assist Mussolini; in return the Bulgarians would be ceded Greek territory. However, if the Bulgarian government refused, Hitler threatened to invade. Bulgaria thus joined the pact on March 1, 1941. Although its forces were part of the occupation of Yugoslavia and Greece, it did not join Operation Barbarossa in June 1941.

Bulgaria was deemed important for Soviet security, and had been an ally of the Germans and thus an ‘enemy’ state. Nazi Germany had urged Bulgaria to join the Tripartite Pact powers after Italy’s invasion of Greece had failed. Hitler wanted to be able to send his forces through Bulgaria into Greece to assist Mussolini; in return the Bulgarians would be ceded Greek territory. However, if the Bulgarian government refused, Hitler threatened to invade. Bulgaria thus joined the pact on March 1, 1941. Although its forces were part of the occupation of Yugoslavia and Greece, it did not join Operation Barbarossa in June 1941.

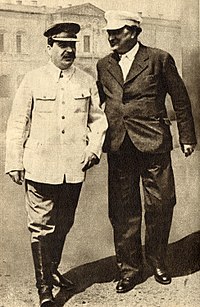

The Bulgarian communist party set up an underground resistance movement called the Fatherland Front in August 1942 which opposed the pro-Nazi government. When Romania changed sides and declared war on Germany in August 1944 its government allowed Soviet forces to cross its territory to attack Bulgaria. In September the Red Army invaded, the Bulgarian communists affected a coup in Sofia, the Soviets occupied the country and the government was overthrown. Stalin then installed a communist regime under the leadership of Georgi Dimitrov (see photo to the left showing Dimitrov talking to Stalin).

East Germany

Following the end of the Second World War, there was hope that Germany would re-emerge as a united, neutral, non-militarised country. However, for the Soviet Union, which had born the onslaught of the Nazi war machine and suffered the loss of approximately 27 million people, control over post-war Germany was key to its future security. Stalin was determined that Germany could never again be allowed to recover, rearm and threaten the USSR. The Soviets were not only determined to install a pro-Soviet regime in post-war Germany and ensure that it was permanently weakened, Stalin also want to exact reparations. However, Germany was a very different case to the other countries that came under Soviet control after 1945 due to its geo-political, strategic and economic importance to both superpowers.

Task OneATL: Thinking and communication skills

1. In pairs, review the situation in Germany following the war. Specifically consider the following and their impact on the situation in Germany:

- The decisions made at Yalta and Potsdam (see chart on the Conferences above)

- The growing tension between the Soviet Union and the Allies within Europe as a whole

- The issue of reparations and how they were implemented on each side

- The different political, economic and social structures that had emerged in each sector before 1949

- The Berlin Airlift

Refer to these pages to help you:

1.1 Theme 1 - Rivalry, Mistrust and Accord (ATL) for further discussion of what was decided at Potsdam

3. Theme 3 - Cold War Crises (ATL) for a more detailed look at the political and economic events in Germany which led up to the Berlin Blockade

2. Having reviewed the steps to Germany's division in 1949 discuss the following questions in pairs:

- At what point do you think that it became apparent that Germany would not be unified?

- Was in fact the division inevitable once the decision had been made at Potsdam to split the country?

- Which side was most to blame for the division of Germany?

Task Two

ATL – Thinking and self-management skills

Using the information above, and the material from your group’s research add notes on a] Soviet motives to dominate each state, and b] extent of Soviet influence by 1945 to a copy of the chart below

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team