3. Role and Importance of Rulers in War

The Role and Importance of Leaders in Medieval Wartime

This page contains links and synoptic content on the role and significance of medieval leaders in war time and peace time.

Guiding Questions:

- What makes a leader as conceived by the medievals?

- What sorts of leadership qualities were important for medieval wars?

- What examples demonstrate leadership in medieval wars?

Leadership:

In the medieval Europe, military leadership in general was hierarchical and often tied with hereditary notions. At the helm was the monarch (King or queen or in the Islamic context, Caliph or Sultan) who had the right to summon h/her subjects for war and was expected to lead in battle and reserve the right to punish any who declined to fight or had deserted battle.

Military leadership position and responsibility was also determined by one's relation to the royal or Caliphal court. In Europe, the higher nobility were a hereditary class of wealthy and powerful families that were seen as natural leaders with a God-given right to lead others and were expected to fulfill that role. This meant that leadership was defined by natural rank and not merit.

In the Muslim world, leadership was endowed based on meritocracy and loyalty to ruler where even freed slaves could become ruler or a general.

For specific examples of the leadership quality of several rulers, see the relevant pages for them in the site.

ATL Skills: Research and Communication

Military Leadership

Read the post here on military leadership in The Hundred Years War.

Questions:

1. According to the article, how was leadership understood and determined in the medieval period?

2. Using the article and your own research, what was significant about Vegetius' De Re Militari regarding leadership? Outline two points.

3. What according to the article and your own research was the effects of Charles VII's reform of military leadership?

ATL Skill: Thinking Critically

Wars are not Won by Heroes

Professor Cathal Nolan argues that it is naive at best and mistaken at worst to think that individuals though heroic feats of courage or some demonstration of impeccable leadership wins wars. He writes:

Whether or not we agree that some wars were necessary and just, we should look straight at the grim reality that victory was most often achieved in the biggest and most important wars by attrition and mass slaughter – not by soldierly heroics or the genius of command. Winning at war is harder than that. Cannae, Tours, Leuthen, Austerlitz, Tannenberg, Kharkov – all recall sharp images in a word. Yet winning such lopsided battles did not ensure victory in war. Hannibal won at Cannae, Napoleon at Austerlitz, Hitler at Sedan and Kiev. All lost in the end, catastrophically.

There is heroism in battle but there are no geniuses in war. War is too complex for genius to control. To say otherwise is no more than armchair idolatry, divorced from real explanation of victory and defeat, both of which come from long-term preparation for war and waging war with deep national resources, bureaucracy and endurance. Only then can courage and sound generalship meet with chance in battle and prevail, joining weight of materiel to strength of will to endure terrible losses yet win long wars. Claims to genius distance our understanding from war’s immense complexity and contingency, which are its greater truths.

Questions:

1. Were medieval wars won on attrition and mass murder as opposed individual acts of heroism? Give clear reasons for your answer with examples.

2. 'Leadership plays a minimal role in war.' To what extent is this true with reference to one medieval war you have studied. (15 marks)

ATL: Communication

Historian Sean McGlynn writes regarding the myths of medieval warfare:

Every period of history has its share of military blunders, inept leaders and poor organisation, but it is a mistake to consider them as the norm in medieval warfare rather than as exceptions to the rule. War in the Middle Ages was fought as competently as in any other period and the era does not represent a hiatus in the evolution of military history. In about 375 BC, Plato wrote in The Republic that it is ‘of the greatest importance that the business of war should be efficiently run’. The Middle Ages channeled their best efforts to this end, and with appreciable success.

Questions:

1. What are some of the reasons according to the author of the article that have led to the misunderstanding or misconceptions regarding medieval wars? Outline one.

2. What are some of the examples given were mistakes or misunderstandings have been made? Outline a few.

Importance of leadership: strong leadership in medieval war was extremely important and necessary for a number of reasons such as victory and survival. Victory or survival through strong leadership was achieved by or demonstrated through:

- Keeping the army unified (religiously, politically).

- Galvanising the soldiers.

- Instilling purpose and value to the conflict.

- Instilling discipline within the ranks.

- Keeping steadfast, firm and resolute.

- Maximising opportunities in a given situation.

- Utilising resources optimally and efficiently.

- Building trust and confidence within the forces, allies, etc.

- Working together - collaboration.

- Being innovative and creative in policy, tactics, strategy, planning, etc.

ATL Activity: Research and Thinking Critically

Importance of Leadership

Examine one battle/conflict you have studied.

How did leadership of those involved affect or alter the outcome of that battle/conflict. The sheet below may help to structure your answer:

Crucibles of Leadership:

Often, the sources record that medieval military leaders reacted to adverse events or personal and traumatic episodes in order to become the kinds of leaders they did. One helpful way of looking at this is the notion of a "leadership crucible" defined by Diana Gabriel as:

trials, tests and failures — points of deep self-reflection that force you to question who you are and what really matters. Characterized by a confluence of threatening intellectual, social, economic and/or political forces, crucibles test your principles, belief systems and core values.

Bennis and Thomas, pioneers in leadership, explain leadership crucibles as follows:

We came to call the experiences that shape leaders “crucibles,” after the vessels medieval alchemists used in their attempts to turn base metals into gold. For the leaders we interviewed, the crucible experience was a trial and a test, a point of deep self-reflection that forced them to question who they were and what mattered to them. It required them to examine their values, question their assumptions, hone their judgment. And, invariably, they emerged from the crucible stronger and more sure of themselves and their purpose—changed in some fundamental way.

Leadership crucibles can take many forms. Some are violent, life-threatening events. Others are more prosaic episodes of self-doubt. But whatever the crucible’s nature, the people we spoke with were able, like Harman, to create a narrative around it, a story of how they were challenged, met the challenge, and became better leaders. As we studied these stories, we found that they not only told us how individual leaders are shaped but also pointed to some characteristics that seem common to all leaders—characteristics that were formed, or at least exposed, in the crucible.

ATL Skills: Research and Thinking Critically.

Task:

Re-examine the leaders you have studied such as:

- Genghis Khan.

- Richard I.

- Saladin.

- Nur al-Din Zengi.

- Kublai Khan.

- Tamerlane (or any other medieval leader).

Identify what crucibles - if any - contributed to forging their attributes as leaders. Use the handout in the link below:

The Role of Women:

The role of women and their leadership qualities is unfortunately still under-represented in medieval studies. This however is being redressed and the emerging academic works is revealing exciting new information and creating a fresh approach within contemporary medieval studies.

Deeper research is revealing that many women assumed leadership roles in various capacities during medieval wars and conflicts. Read the post here outlining 10 such women and here surveying 13 notable women.

Studying this section with Women in Medieval Warfare will be helpful to make relevant links.

Example: Matilda of Tuscany:

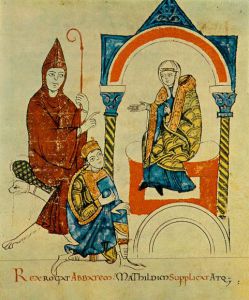

Miniature: Biblioteca apostolica Vaticana, Cod. Vat. Lat. 4922, fol. 7v. The dedication page of Donizo’s 1115 autograph of his Vita Mathildis, depicting the important role assumed by Matilda of Tuscany (1046-1115) in the absolution of Henry IV (1050-1106) at Canossa in 1077. Henry kneels before Matilda's feet in supplication while the Abbot of Cluny points to here. The king prays to the Abbot and pleads with Matilda.

Read about Matilda of Tuscany and complete the worksheet in the ATL activity box below:

Matilda (history of royal women).

Matilda (Britannica).

Matilda (ThoughtCo).

Matilda (Catholic encyclopedia).

Matilda (wikipedia).

IB Docs (2) Team

IB Docs (2) Team