As always, the easiest way to see how to do something well is to look at great examples, and to deconstruct how it has been put together. A well-chosen research topic into one or more literary works has all the benefits of clear primary research analysing the work itself, with opportunities to research the context through secondary sources.

Great Examples

Here you will find examples of students' Extended Essays in Group 1. Both are Category 1 essays, as outlined in Extended Essay - Choosing your Category. Read and consider the structure and quality of the Extended Essay, and then indicate how you would grade them.

Example 1:

Sexuality in The Handmaid’s Tale and Lolita

Research Question: How and why is female sexuality

dehumanized in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale

and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita?

Word Count: 4000

Table of Contents

I. Introduction 3

II. Literature review: socioeconomic/political causes and consequences of sexual abuse. 4

III. Zoomorphism: the animalisation of women into prey, prize and possession. 6

IV. Satanic vs angelic motifs: the paradoxical status of abused women. 8

V. Nature symbolism: using sexuality as a synecdoche for women. 10

VI. Colour symbolism: facilitating abuse through dehumanization. 11

VII. Conclusion 13

VIII. Works Cited 15

I. Introduction

The sexual abuse and exploitation of women can take many forms, including physical and psychological, and happens both behind closed doors and hidden in plain sight. Literature plays an imperative role in offering a comprehensive view of why and how the sexual abuse of women occurs, with writers tackling polar opposite narratives that give insight into the complex minds of individuals whilst reflecting society’s attitude towards such crimes. On one hand, Margaret Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale (Atwood), published in 1985, is a dark dystopia that follows a woman enslaved by a theocratic society for her power of fertility. On the other hand, Vladimir Nabokov’s strikingly jocular Lolita (Nabokov), first published in 1955, is written from the perspective of a man enamored with the teenage daughter of his late wife. These contrasting narratives, the female victim in The Handmaid’s Tale and the male perpetrator of sexual offences in Lolita, lead the reader to question the blurred lines between infatuation and manipulation, exploitation and collectivism.

The purpose of this paper is to explore how and why Nabokov and Atwood construct their narratives, where the exploitation and dehumanization of female sexuality is depicted in two completely different lights. In The Handmaid’s Tale, denoted speculative fiction by Atwood herself (Mead), the abuse of women is enforced by the theocratic government, while the sexual abuse in Lolita occurs behind closed doors and, as a result of the lyrical narrative, the reader feels somewhat empathetic towards the perpetrator. Yet through their use of common literary features, Nabokov and Atwood dehumanize the sexuality and femininity of Dolores Haze, the young girl preyed upon by a pedophile under the pseudonym Humbert Humbert in Lolita; and Offred, a ‘handmaid’ whose sole purpose in the Republic of Gilead is to produce offspring for her Commander in The Handmaid’s Tale. The contrasting narratives and comparable techniques provoke the reader to ponder the relevance of such literature in a society where sexual abuse is still a prevalent issue within households and political institutions. This essay will thus attempt to answer the following research question: how and why is female sexuality dehumanized in The Handmaid’s Tale and Lolita?

II. Literature review: socioeconomic/political causes and consequences of sexual abuse.

In Lolita and The Handmaid’s Tale, Nabokov and Atwood draw on the historical treatment and behaviour of women in their respective societies to explore the nullification of the abuse of female sexuality. Lolita, first published in France in 1955—yet only published in 1958 in the United States—was written by Russian émigré Nabokov (Vladimir). The Handmaid’s Tale, written by Canadian author and activist Atwood, was originally published three decades later in 1986 (Margaret). Consequently, the social contexts of Nabokov and Atwood at their time of writing are vastly different, as evident in their respective works.

In spite of their vastly different social contexts, both novels reinforce the notion that a woman’s sexuality is a man’s possession. Nabokov, having moved to the United States in 1940 (Vladimir), was thrust into post-WWII American culture and witnessed, from a European perspective, its progression throughout the height of the Cold War. In Lolita, Nabokov frequently remarks on the obscene consumerism and idealized gender roles forced upon American society through the media (Colapinto). Despite his infallible infatuation with Dolores Haze—alias Lolita—even Humbert Humbert felt repulsed by her desire for repugnantly vibrant elements of American pop culture: “She it was to whom ads were dedicated: the ideal consumer, the subject and object of every foul poster” (Nabokov; 148); “Mentally, I found her to be a disgustingly conventional little girl” (Nabokov; 148). One of the fundamental elements of Cold War culture was the nuclear family, which reduced the role of the woman to tending to the household and procreation, dubbed “domestic containment” by historian Elaine Tyler May (Postwar). The societal role of women was forced upon girls from a young age, with Disney films and the emergence of rock‘n’roll playing integral roles. This ignited an internal struggle within young girls growing up in the 1950s, where women were expected to present themselves as seductive objects of lust whilst maintaining their premarital purity: “Popular culture capitalized on young women’s struggle between preserving the family and being an object of desire” (O’Keefe; 59). In the context of Lolita, Dolores Haze encapsulates this view of women: she is adored by Humbert purely for what she has to offer sexually rather than intellectually; it is her nymphetical power of sex that entices him.

Furthermore, Nabokov explores the controversial topic of pedophilia in Lolita, drawing on real life events for inspiration, such as the abduction of Sally Horner by convicted rapist and pedophile Frank La Salle in 1948 (Weinman). Yet, the pedophilic acts, which verge on pornography (Baker; 18), often get lost in the lyrical passages, therefore nullifying the severity of Humbert Humbert’s crime. Among sexual abuse experts and psychologists, the debate as to whether child-adult sex is always psychologically dangerous is ongoing (Taylor). The moral status of adult-child sex, according to philosophy professor Kershnar, is dependent on whether consent is informed and free, and who argues that sexual relations between individuals over the age of 18 and prepubescent/pubescent children can indeed be harmless. However, this argument was formulated without data collection or experimental groups, relying only on assumptions to form conclusions, therefore decreasing the validity of the paper. On the other hand, Harrison, a lecturer at Warwick University, stated that arguments in defense of pedophilia further enable perpetrators to commit their crime and support its grounds (Taylor), just as Humbert seeks to justify his actions throughout the novel. Consequently, Lolita, due to Humbert’s quick wit and monstrous fascinations, is an unlikely pairing of comedy and horror (Malcolm).

In sharp contrast to Lolita’s flamboyant and vibrant American influence, the Republic of Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale suppresses all forms of pre-existing American culture. In Gilead, it is forbidden for the handmaids to read or write—essentially experience any form of intellectual stimulation—and unlike during the 1950s, the appearance of a handmaid and her role as biological mother is worthless in comparison with her power of fertility. Atwood wrote The Handmaid’s Tale a decade after second wave feminism concluded (Hewitt; 39-60), intending to highlight the oppressive treatment of women and its potentially destructive future, hence Atwood’s coining of the term ‘speculative fiction’ (Mead). One of Atwood’s conditions for writing The Handmaid’s Tale was to solely include events that have historical antecedents and relevant present-day comparisons. For example, Atwood specifies the prohibition of abortion in Romania, the Bhopal gas tragedy in India and passages from the Bible as sources of inspiration when constructing Offred’s narrative (Mead). Moreover, The Handmaid’s Tale draws parallels with popular fairy tales, namely the Grimm brothers’ Little Red Riding Hood, as Offred and Red are controlled by a greater male power: the patriarchal theocracy and the wolf, respectively (Wilson; 271-94). Atwood parodies visual and thematic elements of the story in her “metafairy tale”, such as sexual and power politics and the use of colour and nature.

The notion that sexual abuse causes psychological damage, enables the suppression of freedom of speech and diminishes a woman’s political voice is key to The Handmaid’s Tale. Weitz argues that the control exercised predominantly by men over women’s lives stems from the social construction of their bodies, which in itself is a political process. In her anthology, Weitz demonstrates how the social construction of women’s bodies is a direct consequence of battles between groups with opposing political agendas. The resulting change in society’s view of a specific feminine issue or phenomenon in turn changes the material resources available to women, which more often than not reflects and reinforces the unequal distribution of power between men and women. Regarding sexual abuse, one in depth study concluded that first and second hand encounters often lead to changes in sociopolitical orientations, predominantly for women than for men (Peterson; 281-90). However, the validity of these results are questionable due to the lack of socioeconomic diversity within the experimental group: the 1984 study was conducted on undergraduates at Alfred University, a small, private college in the US. Conclusively, a number of sources reinforce Atwood’s notion in The Handmaid’s Tale that sexual abuse diminishes female agency and increases subjugation—an idea that transposes into Lolita through Humbert’s control over Dolores, her sexual experiences and her future.

III. Zoomorphism: the animalisation of women into prey, prize and possession.

Both Nabokov and Atwood employ zoomorphism to dehumanize the victims of abuse, thereby rendering their abuse humane and justifiable in the eyes of the perpetrators. Nabokov uses this technique to illustrate how Dolores is Humbert’s possession, like an animal that must be tamed. When it was still a secret from Dolores, Humbert confessed his infatuation with her as though he were a hunter furtively seeking out his prey: “One has to feel elsewhere about the house for the beautiful warm-colored prey” (Nabokov; 49). In this quotation, the “warm-colored prey” is a metaphor for Dolores. Using descriptors such as “warm-colored” connotes with warm-blooded creatures such as mammals, while the archetype of prey suggests that Dolores is to be hunted, attacked and won. Similarly, Dolores removes her bra “to give her back a chance to be feasted upon” (Nabokov; 88). Nabokov uses zoomorphism to transmogrify Lolita from a young girl into a piece of meat that Humbert is hungry for, insinuating that he preys on her for his survival rather than for his lust. Consequently, the vulgarity of his pedophilic cravings is belittled as Dolores is portrayed as a wild animal rather than a human. Moreover, Humbert adopts a possessive tone when Nabokov writes “Precocious pet!” (Nabokov; 49), “Oh, what a dreamy pet!” (Nabokov; 120) and “his monkey” (Nabokov; 213). Nabokov employs zoomorphism to illustrate how Dolores is Humbert’s to possess and tame. The archetype of monkey connotes with playfulness, while pets are generally docile and domesticated animals, thus illustrating how despite Dolores’ lively nature, she is restricted by Humbert’s desires and is rendered his sexual pet. Ultimately, Nabokov uses zoomorphism to dehumanize and animalize Dolores, thereby decreasing the severity of Humbert’s actions.

In contrast to Nabokov’s lascivious use of zoomorphism, Atwood employs this technique to vilify the victims of sexual abuse, insinuating that girls are owned by men even though they are born equals. When describing the handmaids’ comportment, Atwood writes that they take steps “like a trained pig’s on its hind legs” (Atwood; 29). Similarly, after scheduled bathing sessions, Atwood describes Offred’s conduct: “I wait, washed, brushed, fed, like a prize pig” (Atwood; 79). In these quotations, Atwood employs zoomorphism through the use of simile to liken the handmaids to pigs: animals connotative with filth and contamination, whose only source of worth is their meat. By using simile to liken the handmaids to pigs, Atwood demonstrates how they are only valued for their ‘meat’, symbolic of their fertility, whilst their human attributes such as curiosity and desire are prohibited and undesirable. Consequently, the methodic assault of handmaids is deemed acceptable due to the reduced status of women. Nevertheless, Atwood uses zoomorphism through simile and juxtaposition to show the natural affinity women have for freedom: “He pulls down one of my straps, slides his other hand in among the feathers, but it’s no good, I lie there like a dead bird” (Atwood; 267). In this quotation, Offred uses simile to aliken herself to a dead bird while the Commander initiates intercourse at a brothel. She juxtaposes the archetype of “bird”, which connotes with liberty and agency, with “dead”, thereby suggesting that her rights and freedom as a woman have been abolished through sexual exploitation. In both cases, regardless of different socio-political contexts, Atwood and Nabokov employ zoomorphism to demonstrate how depreciating the status of women diminishes the vulgarity and severity of sexual assault, thus undermining women’s greater social standing.

IV. Satanic vs angelic motifs: the paradoxical status of abused women.

Additionally, Nabokov and Atwood employ satanic and angelic motifs to further nullify the crimes of sexual abuse and exploitation, illustrating how value lies in sexuality rather than desire. On one hand, Nabokov uses a satanic motif to demonize the ‘nymphetical’ innocence of young girls to suggest that sex when coupled with attraction is morally wrong. When Humbert observes a ‘nymphet’, he often describes her presence as demonic, calling a nameless Girl Scout “the little deadly demon among the wholesome children” (Nabokov; 17). Once Humbert and Dolores become sexually acquainted, Nabokov writes that she has “the body of some immortal daemon disguised as a female child” (Nabokov; 138). In these quotations, Humbert condemns the desirability of the young girls rather than condemning his own lecherous attraction towards them, hence his labelling them “demons”. Nabokov therefore suggests that although Humbert preys on young girls, it is the girls who are wrong for simply retaining their innocence and attraction. Essentially, Humbert’s abuse is not deemed morally unacceptable. Furthermore, after a sexual encounter with Dolores, Humbert states: “I still dwelled in my elected paradise—a paradise whose skies were the color of hell-flames—but still a paradise” (Nabokov; 166). In this quotation, Nabokov employs the satanic motif through describing Humbert’s paradise as having hell-like characteristics. The “paradise” is symbolic of his sexual experience, although it is tainted by “hell-flames”: symbolic of Dolores’ infantile innocence that has been corrupted. This furthers the notion that Dolores’ desirability is demonic, meanwhile suggesting that women can only be angelic when stripped of their feminine characteristics: thereby demonstrating how worth lies in sexuality rather than desirability.

On the other hand, Atwood employs an angelic motif to glorify the functionality of sex, illustrating how women maintain their virtue by resisting affection. As a handmaid, Offred’s sole purpose is to be a vessel of fertility; her role is not to be desired nor loved. Following the Salvaging, Offred writes: “I don’t want to be a doll hung up on the Wall, I don’t want to be a wingless angel” (Atwood; 298). In this quotation, Atwood describes how Offred does not want to sacrifice her life for her moral code, describing those who hang from the Wall as “wingless [angels]”. The handmaids are the angels who are stripped of their wings when they violate the code of conduct. The symbol of angels suggests that the functionality of sex and methodic rape renders the handmaids pure and wholesome, illustrating how women only retain their innocence by submitting to men and refusing love. Paradoxical to the pastoral interpretation of purity, the handmaids are at their most angelic when they submit to sexual subjugation out of wedlock. Furthermore, the archetype of wings connotes with freedom and agency. When a handmaid, symbolized by an angel, violates the rules, she is stripped of her wings: representative of how women are only truly free when they submit to abuse and repress emotion. The angelic motif used to describe the handmaids glorifies the functionality of sex and fertility and the lack of emotion tied to sexual assault. Conclusively, Nabokov and Atwood use satanic and angelic motifs to illustrate how it is only moral to value a woman for the functionality of her sexuality rather than her desirability. This dehumanization of feminine traits and categorisation into ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ subsequently renders a woman physically and emotionally inferior to her male counterpart, meanwhile limiting her freedom to make socially acceptable choices regarding her body.

V. Nature symbolism: using sexuality as a synecdoche for women.

Similarly to the paradoxical role of purity in sexual abuse, Nabokov and Atwood depict a woman’s essence to be her sexuality, thus diminishing female status physically and socially. To further degrade the status of women, both authors employ nature symbolism to demonstrate how women are only valued for their sexuality and fertility rather than their femininity and emotions. Nabokov employs nature symbolism, namely flower symbolism, to illustrate how women are only as valuable as their sexuality and therefore justifies sexual exploitation. During his defense in court, Humbert asks: “Did I deprive her of her flower? Sensitive gentlewomen of the jury, I was not even her first lover” (Nabokov; 135). In this quotation, Dolores’ “flower” is symbolic of her virginity, as the archetype of flower connotes with fragility and purity. When appealing to a court of law, Nabokov suggests that since Humbert did not ‘de-flower’ Dolores, he should not be persecuted for repeated sexual assault. Nabokov therefore reduces Dolores to her virginity and sexual purity, insinuating that her sexuality is the only characteristic that renders her worth justice. Furthermore, Nabokov uses flower symbolism as a synecdoche for Dolores: “You will dwell, my Lolita will dwell (come here, my brown flower)” (Nabokov; 151). In this quotation, the oxymoron “brown flower” is a metaphor for Dolores, where Nabokov juxtaposes “brown” and “flower”. Whereas flower connotes with purity and fertility, brown often connotes with contamination. Nabokov not only degrades Dolores into solely her sexuality—the flower—but also further devalues her sexuality by describing it as brown, connotative with impurity and filth. Ultimately, Nabokov uses nature symbolism to dehumanize women into just their sexuality, illustrating the justifiable nature of sexual exploitation as judicial worth is not measured by psychological effects..

In addition to Nabokov’s use of symbolism, Atwood uses nature symbolism to demonstrate how a woman’s social value lies exclusively in her sexuality. While Offred’s sole purpose as a handmaid is to bear children, and in spite of her low status, prestigious women covet her fertility: “Even at her age she still feels the urge to wreathe herself in flowers. No use for you, I think at her, my face unmoving, you can’t use them any more, you’re withered. They’re the genital organs of plants” (Atwood; 91). In this quotation, the Commander’s Wife adorns herself in flowers, symbolic of fertility and beauty, to disguise her age and sterility. Offred argues that she is “withered”, connotative to when flowers wither and die and can no longer function as the “genital organs of plants”. Atwood dehumanizes the Wife’s sexuality, illustrating how without the power of fertility she is disposable and worthless. Meanwhile, Offred is equally dehumanized as her only role is to be a surrogate rather than a mother. Nevertheless, the Sisters ironically teach the handmaids that their sexuality is valuable in the collectivist society: “We are hers to define, we must suffer her adjectives. / I think about pearls. Pearls are congealed oyster spit” (Atwood; 124). In this quotation, the pearls, whose archetype is connotative with rarity and purity, are symbolic of the handmaids: they are regarded as uniform vessels of fertility rather than individuals. On the surface, the handmaids are beautiful purely for their fertility and sexuality. However, Offred remarks that her emotional turmoil and trauma, symbolized by the “oyster spit”, is of no concern as long as her fertility is intact, and therefore stays hidden within the “pearl”—otherwise her fertility. In Gilead, she is not required for her emotions and femininity; her only value lies in her pearlescent sexuality. Conclusively, Nabokov and Atwood use nature symbolism to illustrate how women are degraded by social norms until they stand for nothing more than their disposable sexuality.

VI. Colour symbolism: facilitating abuse through dehumanization.

In tandem with the use of nature symbolism, both Nabokov and Atwood use colour symbolism to demonstrate how when a woman’s sexuality is dehumanized, it becomes easier to control and exploit. Nabokov uses colour symbolism to demonstrate the ease with which sexuality can be exploited when already subjugated. For instance, when Dolores falls sick, Humbert attempts to heal her through seduction: “upon an examination of her lovely uvula, one of the gems of her body, I had not seen that it was a burning red. I undressed her. Her breath was bittersweet. Her brown rose tasted of blood” (Nabokov; 240). In this quotation, the symbolism of the colour red is twofold: on one hand it represents Humbert’s burning passion for Dolores as he examines her mouth, otherwise her “gem”—yet another symbol of her sexuality—while on the other hand, it is symbolic of Dolores’ exploited vulnerability, as demonstrated when her “brown rose”, otherwise genitalia, tastes of blood. While red represents passion, it is also the colour of blood and violence. Nabokov juxtaposes these two symbolic meanings of the colour red to demonstrate the often concealed nature of sexual abuse and its psychological effects. This duality is reflected in Humbert’s ability to hide his sexual relationship with Dolores, thereby facilitating him to repeatedly abuse her while Dolores suffers in silence. Nabokov ultimately uses colour symbolism to demonstrate how once dehumanized, a woman’s sexuality can easily be exploited.

Along similar lines, Atwood uses colour symbolism to reduce a woman to her sexuality, thereby facilitating her abuse. When describing the attire that all handmaids are required to wear, Offred writes: “Everything except the wings around my face is red: the colour of blood, which defines us” (Atwood; 18). In this quotation, the colour red, connotative with blood, symbolizes the handmaids’ source of worth: their ability to menstruate and bear children. By reducing a woman to her sexuality and further dehumanizing it through uniform, thereby denying all handmaids a sense of individual identity, her sexual exploitation is facilitated. Moreover, Atwood employs metaphor to demonstrate the destructive power of the handmaids’ degradation: “The tulips are red, a darker crimson towards the stem; as if they had been cut and are beginning to heal there” (Atwood; 22). In this metaphor, the tulips, connotative with love, ironically symbolize the handmaids and their depreciative treatment. The tulips are deep red, symbolic of the vitality of the handmaids and reinforces the notion that their only purpose is to procreate, as illustrated in the previous quotation. Furthermore, Atwood juxtaposes the colour red with “heal”, suggesting that the only path towards healing is acceptance of the handmaids’ abusive treatment: submission to subjugation is their remedy. This in turn enables the enslavement of women physically and psychologically, thereby demonstrating how the belittlement of a woman’s worth and degradation of her sexuality further enables abuse. Conclusively, Atwood and Nabokov use colour symbolism in tandem with complementary techniques to illustrate how the dehumanization of sexuality facilitates and enables the repeated abuse of women, consequently diminishing their social status in the eyes of men and the law.

VII. Conclusion

Through their use of a plethora of literary techniques, Nabokov and Atwood demonstrate how and why female sexuality is dehumanized in their respective novels Lolita and The Handmaid’s Tale. In spite of their contrasting styles and narratives, wherein Humber Humbert is the perpetrator and Offred the victim, both novels explore the degradation of women and the nature of psychological and physical abuse to yield similar conclusions.

The dehumanization of Offred and Dolores’ sexuality was achieved through the use of zoomorphism, satanic and angelic motifs, nature and colour symbolism. One of the primary consequences of these features was the view that women, notably their sexuality and in some cases fertility, are possessions of men and their personal agendas, be it political or otherwise. Furthermore, Atwood and Nabokov demonstrate how instances of abuse and exploitation can be justified and nullified in the eyes of the perpetrator, thus further deepening the sexual power chasm between men and women. The ultimate conclusion, therefore, is that it is not actions nor identity, but rather biology and anatomy, that renders women second-class citizens in comparison with their male counterparts. The purpose of dehumanization, therefore, is to justify this conclusion in all circumstances.

In the context of today’s political and social circumstances, The Handmaid’s Tale and Lolita demonstrate the monstrosity and manipulation hidden within intelligence, education and sociopolitical hierarchies that quietly threatens the fabric of social order and equality. However, while these texts give insight into intrinsic societal issues, this paper does not account for all attitudes regarding the subject of female subjugation. Lolita and The Handmaid’s Tale assume American, or more broadly Western perspectives, thus minimizing the universality of each text’s principal message regarding female sexuality. Nevertheless, Dolores and Offred emphasize the irony in ‘political correctness’ by contrasting sexual exploitation with infatuation and necessity, respectively, bringing to light issues such as the value of women in a seemingly progressive world.

VIII. Works Cited

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid's Tale. 1985. Vintage ed., Penguin Random House UK, 2017.

Baker, George. "'Lolita': Literature or Pornography?" The Saturday Review Archives. The Unz Review, www.unz.com/print/SaturdayRev-1957jun22-00018a02/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2018. Originally published in The Saturday Review, 22 June 1957, p. 18.

Colapinto, John. "Nabokov's America." The New Yorker, 30 June 2015, www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/nabokovs-america. Accessed 25 Apr. 2018.

Hewitt, Nancy A. "Multiracial Feminism Recasting the Chronology of Second Wave Feminism." No Permanent Waves: Recasting Histories of U.S. Feminism, New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers UP, 2010, pp. 39-60. Questia School, www.questiaschool.com/library/120089166/no-permanent-waves-recasting-histories-of-u-s-feminism. Accessed 15 July 2018.

Kershnar, Stephen. “The Moral Status of Harmless Adult-Child Sex.” Public Affairs Quarterly, vol. 15, no. 2, 2001, pp. 111–132. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40441288. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Malcolm, Donald. "Lo, the Poor Nymphet." The New Yorker, 8 Nov. 1958, www.newyorker.com/magazine/1958/11/08/lo-the-poor-nymphet. Accessed 25 Apr. 2018.

"Margaret Atwood." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 26 Oct. 2017. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Margaret-Atwood/11189. Accessed 15 July 2018.

Mead, Rebecca. "Margaret Atwood, the Prophet of Dystopia." The New Yorker, 17 Apr. 2017, www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/17/margaret-atwood-the-prophet-of-dystopia. Accessed 9 July 2018.

Nabokov, Vladimir. Lolita. 1955. Penguin Classics ed., Penguin Random House UK, 2015.

O'Keefe, Bridget. "Happiness, Womanhood, and Sexualized Media: An Analysis of 1950s and 1960s Popular Culture." New Errands: The Undergraduate Journal of American Studies [Online], 2014, p. 59, journals.psu.edu/ne/article/view/59261. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Peterson, Steven A., and Bettina Franzese. “Sexual Politics: Effects of Abuse on Psychological and Sociopolitical Attitudes.” Political Psychology, vol. 9, no. 2, 1988, pp. 281–290. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3790957. Accessed 9 July 2018.

"Postwar Gender Roles and Women in American Politics." History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, Office of the Historian, 2007, history.house.gov/Exhibitions-and-Publications/WIC/Historical-Essays/Changing-Guard/Identity/. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Taylor, Matthew. "Paedophilia thesis comes under fire." The Guardian, 2 Dec. 2004, www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/dec/02/research.children. Accessed 10 July 2018.

"Vladimir Nabokov." Britannica Academic, Encyclopædia Britannica, 19 Jun. 2018. academic.eb.com/levels/collegiate/article/Vladimir-Nabokov/54606. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Weinman, Sarah. "The Real Lolita." Hazlitt, Penguin Random House, 20 Nov. 2014, hazlitt.net/longreads/real-lolita. Accessed 10 July 2018.

Weitz, Rose. The Politics of Women's Bodies: Sexuality, Appearance, and Behavior. New York, Oxford UP, 2003.

Wilson, Sharon Rose. "Off the Path to Grandma's House in The Handmaid's Tale 'Little Red Cap.'" Margaret Atwood's Fairy-Tale Sexual Politics, Jackson, MS, UP of Mississippi, 1993, pp. 271-94. Questia School, www.questiaschool.com/library/7409660/margaret-atwood-s-fairy-tale-sexual-politics. Accessed 15 July 2018.

The Reflections for this student and this essay can be found here:

Although I knew from the beginning of this process that I wanted to write my extended essay in English literature, I was torn over which books to choose. After putting together a potential reading list and grouping novels together by shared themes, I decided to pursue the dehumanization of female sexuality as an overarching concept. I found the contrast between dystopianism and mid-twentieth century literature intriguing, hence my choice of Lolita and The Handmaid's Tale. Initially, I struggled to put my ideas into a concise question, as I was not sure how to strike the right balance between contextual research and literary analysis. Upon meeting with my supervisor and receiving some guidance, we agreed that I would use societal standards for women as an avenue for research. However, I am concerned about the potential lack of academic resources that are relevant to my study.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Once I finished reading The Handmaid's Tale and Lolita, I decided to completely change my area of focus: researching why novels about controversial topics such as paedophilia and sex slavery were accepted by the mainstream. Despite previous concerns, there is an abundance of academic resources about these topics- so many that I find it hard to balance my time between contextual research and literary analysis. I clarified this issue with my supervisor as he explained the structure of a compare and contrast literature essay and what the different components entail. My biggest challenge so far has been drawing parallels between the novels: on one hand, The Handmaid's Tale qualifies as speculative fiction, while Lolita is a drama. One obstacle that I am currently facing is choosing which literary techniques to analyze for the essay, as there is such a wide range of choice in both novels.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In addition to developing my understanding of Lolita and The Handmaid’s Tale in terms of their literary merit, the EE writing process taught me valuable research skills and enhanced my contextual appreciation. When I started writing, the essay section I found most difficult regarding structure and content was the literature review. I had never encountered this style of writing before, and therefore spent some time filtering through research in order to obtain the most reliable sources, and ensuring that all opinions were cited so as to write as objectively as possible. The significance of this section only struck me much later in the EE process when I was analysing quotations. By reading research papers that supported my thesis in the literature review, I was able to answer the so what? question that often arises when studying literature: how the different literary elements of a work construct a social commentary. Another question that guided me was “in what way is my essay original and how will it be remembered?” Combining the literature review and close-text analysis of Lolita and The Handmaid’s Tale allowed me to compare and contrast the two works to produce a uniquely developed conclusion that is as much of a social criticism as it is a literature essay.

Word count: 500

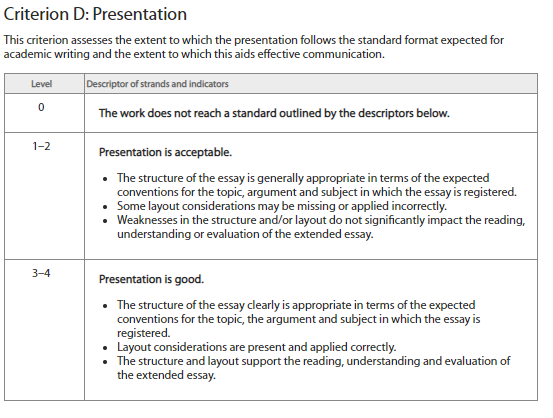

How effective is this Extended Essay?

Consider the Assessment Criteria, especially Criterion E for Engagement, which looks exclusively at the Reflections and does not consider the quality of the essay itself. How would you grade this essay for these five criteria:

Take a look at the examiner's comments and marks and compare them to your own:

A: 5

B: 6

C: 11

D: 4

E: 6

Overall: 32 (A)

This is a very strong essay indeed, with sharp focus and ample effective analysis of the primary sources. Its key strength was a very strong Literature Review, in which the context and premises of the research were set effectively. The section headings allowed the structure and the development of the argument to be clear.

Be the Examiner

Below you will find another example of a literary Extended Essay for Category 1. Using the same process and procedure, decide what you would give the essay, and what you can learn from it (for good and not so good). Please note that in the student's original essay, footnotes were present and accurately cited:

EXTENDED ESSAY, ENGLISH A: CATEGORY 1

THE MOTIF OF TRANSFORMATION

IN FEMINIST LITERATURE

To what extent does Jane Austen employ the motif of transformation in

Pride and Prejudice to further the goals of the feminist movement?

Word Count: 3,933

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of contents………………………………………………………………………………… 1

Introduction……………………………………………………………………............................ 2

Literature Review……………………………………………………………….......................... 6

Essay

i…The motif of unconventional characters……….………………………………………. 9

ii…The use of the epistolary form………....………………………………………………. 10

iii…The motif of flawed marriage proposals....………………………………………….... 13

iv…The symbolism of the human eye.……...……………………………………………...15

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………….........18

Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………...........20-21

INTRODUCTION:

Pride and Prejudice, arguably Jane Austen’s most renowned novel, begins with the feminist observation:“a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” Austen, an English author born during the Age of Enlightenment (1730-1815), focused her literary works on the feminist agenda; she is commonly known for delivering, through her novels, social commentary and critique about the lives of the British landed gentry of her time. In Pride and Prejudice, Austen compellingly contrasts the eccentric Bennet family with other more genteel acquaintances, cleverly mocking the flaws of English society in the late early nineteenth century. Through a feminist lens, Pride and Prejudice explores the hardships that unmarried women endured during that politically divided and narrow-minded period in Great Britain’s history.

At the start of the nineteenth century feminism began as a subcurrent, introspective concept in the minds of female activists, not a bold, outspoken movement meant to upheave entirely the status quo. Because women and men in nineteenth century England were not treated as equals, women filled their stereotypical gender roles of the time, such as homemakers and well-behaved wives; the ideal man was wealthy and influential - capable of supporting his wife. Women internalized opposition to a patriarchal culture, and simply accepted that the success of their marriage and the bearing of sons was society’s true measure their worthiness. By taking this series of widely-accepted social mores and turning them upside down, Austen exposed the flaws of her society, and showed the necessity of avoiding a foregone conclusion that first impressions absolutely and indefinitely defined people. Austen dove beneath the surface, primarily through the use of the transformation motif, to advocate equality and meaningful relationships between individuals. This initiative, in itself, was the primary aim of the feminist movement.

The feminist movement has often been divided into three “waves.” The first wave occurred in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the United Kingdom and the United States; the second wave took place from the early 1960s to the late 1980s. The third wave began in the early 1990s in order to respond to the widely perceived“failures” of the second. Subcategories of the feminist movement included: anarcho-feminism; theoretical feminism; Socialist and Marxist feminism; radical feminism; liberal feminism; and black feminism.

Jane Austen’s works themselves, especially Pride and Prejudice, could fit under at least two of the feminist subheadings. The first is theoretical feminism, which is a branch of the movement which critiques the flaws of society and politics, but focuses on promoting women’s rights. This theory explores themes such as sexual objectification, patriarchy, stereotyping, discrimination, and oppression; some of which are addressed Austen’s frequent use of unconventional female and male characters. Her work does not focus solely on the promotion of women’s rights but, rather, views women and men as equal in all senses of the word.

Jane Austen developed female characters who maintained and proved their equality, through their words, choices, and actions. This liberal feminist approach advocates equal interaction between genders to create a catalyst for transformation in society. Austen explores the goals of the feminist movement through the motif of transformation in Pride and Prejudice. By allowing characters from drastically different ends of the social spectrum to be introduced and interact without breaking the rules of propriety or changing the structure of society, Austen challenged the norm and did something nearly unthinkable at the time: matching two country girls with two respected, eligible, wealthy bachelors in her novel. In so doing, she effectively demonstrated that the gaps between gender and class could, in fact, be bridged.

In Pride and Prejudice, Austen places Elizabeth “Lizzy” Bennet, the protagonist, on a path of self-discovery through a series of interactions with other characters as Lizzy rebels against the norms of society. Some of the more relevant characters include: Mr. Bennet, an indolent bibliophilic teaser, and his matchmaking wife; Lizzy’s elder sister Jane and her younger sisters, Mary, Kitty and Lydia; Charlotte Lucas, Lizzy’s level-headed best friend; the friendly Charles Bingley of Netherfield and his egocentric sister, Caroline; Lizzy’s socially awkward cousin, Mr. Collins; the reckless and irresponsible George Wickham; the cold and condescending Lady Catherine De Bourgh and her daughter Anne; Lizzy’s future husband, the proud Mr. Darcy of Pemberley and Derbyshire; Darcy’s cousin, Colonel Fitzwilliam; and Mr. Darcy’s charming younger sister, Georgiana.

Austen subjects nearly each of these characters to a number of changes throughout the course of Pride and Prejudice, using the motif of transformation. She employs this motif to further the goals of the feminist movement in several ways. First, she selects a strong and independent female as the protagonist of the novel, exposing a wider audience to the real strength of women. Second, the women in the story are the catalyst for change. Third, the leading couples in the novel eventually evolve to treat each other as equals, despite differences in social and economical status, age, and gender.

Austen’s use of the motif of transformation is an overarching technique through which characters, opinions, and actions are transformed over the course of her novel. Plot twists, ideas, and symbolism transform her characters as the story unfolds, furthering the aims of the feminist movement. Austen effectively expresses the overarching motif of transformation in Pride and Prejudice by using numerous tricks of the trade, including: 1.) the motif of unconventional characters; 2.) the use of the epistolary form; 3.) the motif of flawed marriage proposals; 4.) the symbolism of the human eye.

LITERATURE REVIEW:

Being influenced by authors and philosophers who were against the notion of prejudice, as well as novelists who dealt with feminist themes in their works, Austen embraced feminism, which ultimately became a clear theme in her novels.

In 1811, when Austen was in her thirties, she published her first novel under the pseudonym “A Lady.” While authors such as Mary Ann Evans and the Brontë Sisters published their works under male pseudonyms (George Eliot and Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell respectively), Austen chose a pseudonym which deliberately announced her gender. Austen’s prominent female influences included Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823), Fanny Burney (i.e. Madame d’Arblay, 1752-1840), Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), and Madame de La Fayette (1634-1693).

Helena Kelly, author of Jane Austen, the Secret Radical, argues that Austen was also influenced by two prominent male figures, including the anarchist-philosopher William Godwin, and the political radical, Edmund Burke. Kelly adds that Jane Austen was also heavily influenced by Burney’s Cecilia (Memoirs of an Heiress), and that Austen was inspired by the last chapter of Cecilia, in which the words “pride and prejudice,” were used exactly three times in all capital letters. Ironically, Pride and Prejudice was originally titled “First Impressions.”

Elaine Bander of the Jane Austen Society of America, however, questions the link between Burney’s Cecilia and Austen’s Pride and Prejudice. Bander believed that “Cecilia and Pride and Prejudice share only two elements. First, both heroines are courted by a man whose family pride revolts against their match, and second, both novels offer an ironic version of a moral.”

Austen makes numerous references to Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho in Northanger Abbey (published 1817) and according to Helena Kelly, Austen would have been, to some extent, familiar with the works of political writers of the time. Further, Kelly suggested that Austen may have “borrowed the setup for Sense and Sensibility directly from Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Women.” She also postulates that the repercussions of the French Revolution of 1789 influenced Austen, who was hence inspired by Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. In his works, Burke boldly confessed that “we are generally men [...] that, instead of casting away all our old prejudices, cherish them to a very considerable degree.” Kelly adds that the term “prejudice” in the 1790s referred to more than bias or the habit of being overly judgemental; that it represented “tradition, ‘inbred sentiments,’ [and] unquestioned cultural assumptions.”

Austen took a decidedly unconventional approach when writing Pride and Prejudice; the novel diverged from her usual structure, challenging the norms of English society at the time. Kelly notes that, while it was rare for Austen to ever venture higher than a baronet (the lowest hereditary title in the peerage) when creating her characters, Pride and Prejudice was the exception. Austen directed her discourse toward every offensive feminist class: earls, high-ranking noblemen; baronets, knights; and gentlemen. According to Kelly, “eighteenth-century writers were deeply uneasy about making their upper-class characters marry out [to members of the lower class].”

The British Library’s Professor Kathryn Hughes Hughes referenced Pride and Prejudice and Lizzy Bennet’s antagonist, Caroline Bingley, in a 2014 article. She mentions that young girls at the time were not expected to outwardly focus on finding husbands, and that women desired marriage because it would allow them to become mothers. In her article, Professor Hughes mentions that that the genders lived in “separate spheres,” living segregated daily lives until they joined each other once more “at breakfast and again at dinner.” Hughes adds that middle-class women attracted men not through their “domestic abilities,” but through their coachings in numerous “accomplishments.” The issue of sex-segregation in the nineteenth century is frequently addressed in Pride and Prejudice, where Austen criticizes the senseless notion of the so-called “accomplished” woman, and questions the necessity of this widely accepted separated lifestyle.

ESSAY:

1. The motif of unconventional characters.

Through the recurring use of unconventional main characters in her novel and the dialogues and discourses between them, Austen rejects the old dichotomy between the treatment of male and female roles in society, satirizes class differences and reveals how it is not necessary to conform to the norm in order to be a credit to one’s gender. At one moment in the eighth chapter of the novel, Caroline, Mrs. Hurst, Bingley and Darcy are gathered in a room, discussing Elizabeth’s appearance upon her entering the Netherfield breakfast-parlor earlier that day. Caroline and Mrs. Hurst criticize the state of Elizabeth’s dress and hair; Mr. Bingley, however, argues that there had been nothing wrong with Miss Elizabeth’s appearance when she first arrived, and that her clothes had escaped his attention, adding that Elizabeth’s behavior “[showed] an affection for her sister that is very pleasing.”

As Caroline continues to attack Elizabeth, commenting on Lizzy’s uncle’s career as a tradesman and his home in the working-class district of London, Mr. Bingley says that even if Elizabeth had “uncles enough to fill all Cheapside, it would not make them one jot less agreeable.” His kindness in the face of discrimination is unconventional, especially since Darcy, who has yet to be humbled by Elizabeth, initially seems to agree with Caroline’s points, and says that the Bennet sisters’ connections “must very materially lessen their chance of marrying men of any consideration in the world.” Ironically, at the end of the novel, his perceptions are entirely transformed.

Later, when Elizabeth is formally introduced to and joins this hypocritical group, they begin to discuss the topic of female accomplishments. As Darcy and Caroline heap things onto their list of what makes a woman accomplished in their eyes, Darcy declares that he “cannot boast of knowing more than half-a-dozen [women] that are really accomplished.” Countering, Elizabeth says she is surprised that Darcy knows any women at all that match that description, and adds that she “never saw such a woman herself.” Elizabeth’s disbelief in Darcy’s initial ideals illustrates Austen’s conviction that a woman’s worth should not be measured by the list of her accomplishments: Austen seizes upon this conflicted discussion to reveal the hypocrisy of discrimination, using unconventional characters to deliver the message.

2. The epistolary form.

In Austen’s novel, the most common form of communication between characters is done in person, and any other form of interaction between them is carried out in the form of private letters, also known as “the epistolary form.” These letters, in Pride and Prejudice, tend to reveal a character’s innermost thoughts and give insight into their personal lives - letters, in this case, are a means of allowing characters to be more honest than the rules of propriety would have allowed them to be under ordinary circumstances, and are a way of conveying truths that normally could not be spoken aloud.

In a letter mentioned from William Collins to Mr. Bennet announcing his intention to visit Longbourn, the Bennets’ estate, Collins wrote that the “disagreement subsisting between yourself and my late honoured father always gave me much uneasiness, and since I have had the misfortune to lose him, I have frequently wished to heal the breach [...].” He adds that as a clergyman, it is his duty to promote peace in all families, and that his “present overtures are highly commendable [...].” In this self-aggrandizing letter, Collins reveals much more about his character than he could have with the spoken word. Ironically, upon meeting Mr. Collins, any positive opinion that the Bennets may have formed about him based on his letter transforms from positive to derogatory.

Certainly the most impactful letter in the novel, is the letter from Darcy to Elizabeth in the thirty-fifth chapter. In this letter, he apologizes for his conduct and the failings of his character, and explains to her everything that would have been too risky to convey in person. “You may possibly wonder why all this was not told you last night,” writes Darcy, “But I was not then master enough of myself to know what could or not to be revealed.”

Referring to Darcy’s soulful epistolary apology to Lizzy after botching a marriage proposal, Helena Kelly notes: “A more conservative character, in a more conservative novel, wouldn’t accept that his behavior needed to be explained. Nor would he be open to being reformed.” Not only is Darcy Elizabeth’s senior by several years, but Kelly adds that he is also the wealthy master of a large estate, and that the conduct of such an influential character “like Darcy” wouldn’t have been questioned at the time. Hence, directly addressing Elizabeth in writing as an equal, when the society of nineteenth century England would classify her as his inferior, acts as a catalyst to transform their relationship.

Not only is this letter an eye-opener for Elizabeth, but the man risks his reputation through the delivery of this letter. Darcy regrets his conduct and feels a need to explain his actions. The letter is profusely apologetic and takes up the majority of that chapter, and again, Kelly argues that his letter is written from the heart. Everything that he couldn't say in person, everything that he needed Elizabeth to know, was related in that letter. Through this letter, he not only succeeded in transforming Elizabeth’s opinion of him and, by extension, the opinion of her family members; he also transformed himself. Elizabeth does eventually accept his hand in marriage. Both of them are properly humbled thanks to his letter and Elizabeth, who would have never married any man unless she loved him, finally accepts his proposal. “What do I not owe you! You taught me a lesson,” says Darcy to Elizabeth in the fifty-eighth chapter, “hard at first, but most advantageous. By you, I was properly humbled.”

3. The motif of flawed marriage proposals.

Austen uses the motif of flawed marriage proposals to show the expectations that were placed upon both men and women at the time in relation to matrimony, as well as a woman’s need to be financially secure and protected before her parents or guardians passed away. She also shows that the expectation of the era was to be married for financial security as a priority, rather than being wed out of love. The pressure to be a married woman before the age of thirty was significant in their society, and the shame of the possibility of becoming a spinster pushed some women to enter a union which primarily guaranteed their health and safety, rather than their happiness.

Elizabeth Bennet received two flawed proposals during the story. In the first proposal, Mr. William Collins bores Elizabeth with his views on the benefits of marriage. As if he were delivering a persuasive argument rather than a romantic proposal, Collins gives three reasons for marrying Elizabeth: first, it “sets the example for matrimony in his parish,” 2.) second, he is “convinced that it will add very greatly” to his happiness, and third, it was the advice of the “very noble lady,” his patroness, to get married as soon as possible. Elizabeth rejects Collins’ proposal, offended by its lack of passion and treatment of her as a lesser being. Mrs. Bennet, ever the matchmaker, is furious that Elizabeth would give up such an advantageous match.

Darcy’s proposal to Elizabeth (Chapter 34) lacked in real evidence of his affection, and inadvertently expounded on the inferiority and the vulgarity of her family. According to Elizabeth, “He spoke well, but there were feelings besides those of the heart to be detailed, and he was not more eloquent on the subject of tenderness than of pride.” These things, in the mind of Elizabeth, are “very unlikely to recommend his suit.” Angry at the way he delivers his proposal, and angry at the way he separated Mr. Bingley from her sister (Jane) and ruined their chances of happiness, Elizabeth gives Mr. Darcy a proper set-down, asking why he told her that he liked her, when he only seemed to do it against his will, his reason, and his character. She says, that he “could not have made [her] the offer of [his] hand in any possible way that would have tempted [her] to accept it.”

After Darcy has an interview with Mr. Bennet to ask for permission to marry Elizabeth (Chapter 59), Mr. Bennet speaks to his daughter. Clearly shocked that her feelings have changed so much from the way she originally felt about the wealthy gentleman, Bennet worries that the union will not make her happy. “Have you any other objection than your belief of my indifference?” asks Elizabeth. When Mr. Bennet replies that he has “none at all,” Elizabeth, with tears in her eyes, declares that she loves Mr. Darcy. Mr. Bennet declares that he gave Mr. Darcy his consent, but says that her “lively talents” would place her “in the greatest danger in an unequal marriage.” Elizabeth reassures him one last time of how strongly she feels for Mr. Darcy. “If this be the case,” says Mr. Bennet, “he deserves you. I could not have parted with you to anyone less worthy.” Thus, the flawed but eventually rectified proposed transforms Lizzy’s father as well.

4. The symbolism of the human eye.

It is often said that the eyes are the window to the soul. Jane Austen’s characters undergo an inner transformation in the story which is frequently interpreted through their gaze. Austen uses the symbol of eyes in the novel as a tool to reveal hidden truths and show the different ways in which a person may be metaphorically “blind.” Since Austen uses eyes as a symbol for intelligence, she frequently emphasizes the importance of “fine eyes” in a potential suitor. Through the repetitive use of the symbol of eyes in her story, Austen reveals how characters feel for each other, as well as their resilience, by describing the intensity of their gaze.

The word “eyes” is used exactly fifty-two times in Pride and Prejudice, more times than the word “lips,” which appeared forty-four times, or the word “hands,” which was introduced only seven times in the novel. The majority of the usage of the word “eyes” in Pride and Prejudice describes Elizabeth Bennet’s “fine eyes.” In fact, throughout the better part of the exposition of the novel in which Darcy arrives in Meryton and hurts Elizabeth’s feelings at the ball, Darcy discovers an unbidden obsession with Lizzy’s eyes, on which he comments more than once to his best friend’s snarky sister, Miss Caroline Bingley. Darcy’s obsession with Elizabeth’s dark eyes is a recurring theme throughout the novel.

Darcy’s opinion of Elizabeth transforms when he sees her up close, and he comments on how “[her face] was rendered uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of her dark eyes.” When he is in a ballroom with Miss Bingley, he says that "[his] mind was more agreeably engaged,” and that he had “been meditating on the very great pleasure which a pair of fine eyes in the face of a pretty woman can bestow.” Later, he says that Elizabeth’s eyes “were brightened from the exercise” of having walked all the way to Netherfield. “It would not be easy, indeed,” says Darcy to Caroline later on, “to catch their expression, but their colour and shape, and the eyelashes, so remarkably fine, might be copied.” Later, Sir William Lucas confesses to Darcy that Elizabeth’s “bright eyes” are also “upbraiding him.”

As a strong female protagonist, Elizabeth only had tears in her eyes on few occasions. Elizabeth has tears in her eyes her sister Lydia’s elopement with George Wickham. She also, in layman terms, “teared up” when speaking of Fitzwilliam Darcy later in the novel, accepting her love for him on equal terms. By the end of the story, Elizabeth underwent an impressive transformation - her opinion is completely changed where Darcy is concerned, and while all the physical properties of her eyes remain the same, the expression in them is new. At a time where ladies had to carefully guard their emotions behind an air of composure, the expression of Elizabeth’s eyes are enchanting to Darcy and illustrate the power of transformation.

CONCLUSION:

Austen effectively expresses the overarching motif of transformation in Pride and Prejudice through numerous feminist techniques, including the motif of unconventional characters, the epistolary form, the motif of flawed marriage proposals, and the symbolism of the human eye. She reveals the hypocrisy of discrimination, rejects the idea of stereotyped gender roles, and satirizes class differences, expounding on the merits of marriages borne of love rather than greed. She also shows how letters can convey unspoken truths, and she reveals the powerful, transformative sway that the expression of a person’s eyes can have.

Margaret Kirkham, author of “Jane Austen, Feminism and Fiction,” suggests that “Austen [told] the truth through a middling irony which [some] might misread, but which [Austen] hoped readers of sense and ingenuity would not.” This notion of Kirkham’s, according to Christine Marshall, contributing author to the JASNA*, has led to what is “arguably the richest vein of [feminist] Austen criticism ever.” Marshall observes that “critics [of Jane Austen] have found that both [her] style and her subject matter are responses [...] to the patriarchal English gentry society in which women’s lives were constricted in ways that men’s lives were not.”

A critic mentioned by Marshall (Marilyn Butler) claims that “Austen was not a feminist,” and that the opinions expressed in her works were “not liberal, but reactionary.” This essay disagrees emphatically with that view and demonstrates that Austen, through a variety of different artistic techniques and the employment of the motif of transformation, expose the societal flaws in nineteenth century England and consequently championed the equal rights of men and women, and the feminist movement, in her novel without “offending or incurring reprisals.”

Jane Austen crafted a literary work portraying her belief that equality between the genders is not an unattainable ideal, but an achievable milestone. Pride and Prejudice is a novel that proves that it is wrong to judge women and men by their class, gender, wealth, or appearance, and that it would be a credit to our intelligence and human compassion to judge them instead, in the more recent words of Martin Luther King Jr., “by the content of their character.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(MLA Citation)

Armitage, Helen. “12 Women Writers Who Wrote Under Male Pseudonyms.” Culture Trip, The Culture Trip Ltd. , 23 Apr. 2015, https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/usa/articles/12-female-writers-who-wrote-under-male-pseudonyms/.

Austen, Jane. Pride and Prejudice. Penguin Classics, 1996, Turtleback School & Library Binding Edition.

Bander, Elaine. “From Cecilia to Pride and Prejudice: ‘What Becomes of the Moral?’” Jane Austen Society of North America (JASNA), JASNA, 2013, www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol35no1/bander.html.

Bio 2017. “Jane Austen.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 28 Apr. 2017, www.biography.com/people/jane-austen-9192819.

Crossman, Ashley. “What Is Feminist Theory?” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 11 Aug. 2017, www.thoughtco.com/feminist-theory-3026624.

Dorey-Stein, Caroline. “A Brief History: The Three Waves of Feminism.” Progressive Women's Leadership, Progressive Women's Leadership, 24 Sept. 2015, www.progressivewomensleadership.com/a-brief-history-the-three-waves-of-feminism/.

Ferber , Michael. “Chapter E.” Dictionary of Literary Symbols, Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp. 70–71. http://www.mohamedrabeea.com/books/book1_4209.pdf

History.com Staff. “Enlightenment.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2009, www.history.com/topics/enlightenment.

Hughes, Kathryn. “Gender Roles in the 19th Century.” The British Library, The British Library, 13 Feb. 2014, www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/gender-roles-in-the-19th-century.

Kelly, Helena. “Chapter 4, ‘All Our Old Prejudices," Pride and Prejudice.” Jane Austen, The Secret Radical, Alfred A. Knopf, 2017, pp. 112–154.

King, Martin Luther. “‘I Have a Dream.” "I Have a Dream," Address Delivered at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (August 28, 1963), Stanford University, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/king-papers/documents/i-have-dream-address-delivered-march-washington-jobs-and-freedom.

Lewis, Jone Johnson. “What Is Liberal Feminism? How Does It Differ From Other Feminisms?” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 31 Oct. 2016, www.thoughtco.com/liberal-feminism-3529177.

Marshall, Christine. Persuasion, Journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America, 1992, "Dull Elves" and Feminists: A Summary of Feminist Criticism of Jane Austen. pp. 39–44, http://www.jasna.org/assets/Persuasions/No.-14/marshall.pdf

Pant, Vivek. “What Are the Different Types of Feminism?” Quora, Quora, 24 May 2015, www.quora.com/What-are-the-different-types-of-feminism.

How much of Extended Essay - Literary Examples have you understood?

Feedback

Which of the following best describes your feedback?

Twitter

Twitter  Facebook

Facebook  LinkedIn

LinkedIn